This article, reported by GroundUp, first appeared on www.groundup.org.za on April 7.

For more than 60 years, the state has conducted regular dagga eradication programmes in rural Eastern Cape, but this has failed to stop the harvest

The villagers start to keep watch in January. They’re waiting for police helicopters to thud over the hills.

Every year, for nearly three decades, their plantations have been poisoned towards the end of summer, right before harvest time, leaving behind fields of withered stalks.

“We hear rumours that they are coming, that they’ve started spraying nearby,” says one resident, a middle-aged woman, when GroundUp visited last month.

“Then we know the helicopters will be arriving soon, but there is nothing we can do.”

The village of 32 huts lies near the base of a steep valley outside Lusikisiki, Eastern Cape, and is accessible only on horseback or by foot.

Walking hard, the trek takes an hour from the nearest dirt road – one must descend a rocky path, wade through a river and climb a narrow, crumbling ridge. It takes longer if weighed down by infants, groceries or large sacks of dagga.

A waterfall churns further upstream. In the wet season, the water silts up and turns a pale, milky brown. The settlement looks out over the river, which is dwarfed by green cliffs. Donkeys, chickens and goats move between blue rondavels, and grazing cattle are herded by young boys with sticks.

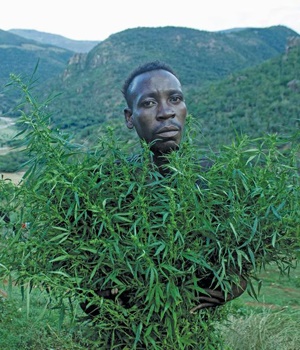

In front of each hut, protected from the livestock by wire fences and dry thorn branches, is a dense field of crops. Other than a few stalks of maize and sorghum, the fields are filled with marijuana shrubs.

Dagga farming sustains entire communities in the rural Eastern Cape, and is an important cash crop in a deeply impoverished subsistence economy.

It has also been illegal since 1929. For more than 60 years, the state has conducted regular eradication programmes, but it has failed to halt the practice, which is sustained by consistently high demand and a lack of alternative income for the farmers who produce it.

At first, police squads marched into villages and uprooted plantations by hand, burning whatever they found and booting suspects into jail. They switched to herbicides in 1980, dispensing chemicals using hand-held pumps. This way, one policeman could “do the work of 78”, a major general named CF Zietsman told reporters at the time. By the end of the decade, helicopters had replaced ground patrols, expanding the operation’s reach and enabling pilots to wipe out entire fields within minutes.

Today, a small group of activists is fighting to stop the spraying programme, arguing that it is unconstitutional, environmentally damaging and a severe health risk. In the meantime, Pondo villagers wait once more for helicopters to drop from the sky.

Pam*, a 57-year-old village resident, last heard the helicopter motors in March last year.

Knowing her marijuana crop would almost certainly be destroyed again – her plot, about half the size of a football pitch, is right in the middle of the village – she walked slowly uphill to wait.

“I get afraid whenever they come,” she says. “I know what I’m doing is illegal. But it’s my only way of making any money.”

At 7.30am, she has just finished her morning’s work chopping down chest-high marijuana bushes with a sickle. Men and women walk past with marijuana bundles balanced on their heads.

“I can’t spend any longer in the fields today. I have arthritis,” she tells me. She will spend the rest of the day sleeping, preparing food for her grandchildren and cleaning her harvest.

Dagga leaves are no good for smoking and must be stripped. The flowers, or “buds”, carry the psychoactive compounds that make people high.

“The poison drifts into our homes when they spray,” Pam says. “It makes us sick. It kills our mealies. Our animals fall ill when they eat the plants.”

The poison is glyphosate. It was patented by agrigiant Monsanto in 1974. Now the world’s top-selling herbicide, it works by inhibiting the production of essential amino acids and kills any plant not genetically modified to withstand its effects.

The best-known glyphosate formulation sells under the brand name Roundup. It is used widely in South Africa to control weeds, remove invasive plants from rivers and dams, and to spray road and railway verges. The SA Police Service uses a different formulation called Kilo Max to target marijuana fields, insisting that it poses no threat to human and animal life, or to environmental health.

But glyphosate’s safety has recently been challenged internationally, and was declared a “probable carcinogen” by the World Health Organisation’s International Agency for Research on Cancer in March last year. It also drew formal objections in Europe from a prominent EU public health committee last month.

Local opposition to marijuana spraying is not new. In 1990, a coalition of civil society organisations in the former Natal province successfully lobbied government to ban the use of paraquat, a different herbicide, during its aerial eradication programmes. In 1995, they sought an interdict against the police for using glyphosate, claiming it was “highly toxic to humans”, but failed. Now, the Dagga Couple – whose crusade began when they were charged with dealing dagga in 2010 – are leading a new campaign.

“South Africa is the last country in the world to spray glyphosate on so-called drug plantations from the air,” said Jules Stobbs, one half of the activist pair. “We see this as a human rights issue.”

Colombia suspended its own 20-year aerial eradication programme targeting coca plantations after the International Agency for Research on Cancer findings were published last year.

Stobbs’ not-for-profit organisation, Fields of Green For All, launched legal proceedings against the police earlier this year, partnering with the Transkei Animal Welfare Initiative and the Amapondo Children’s Project.

In January, attorney Ricky Stone submitted a letter to the police on their behalf, requesting the “immediate” suspension of glyphosate spraying in the Eastern Cape, as well as an independent review of its “effectiveness, appropriateness and compliance” with local and international regulations. The police refused, but have not yet conducted any aerial eradication operations this year.

At dusk, the villagers sit outside their homes, processing the dagga. Bunches hang to dry inside every hut, the tiny buds choked with seeds. Contrary to police reports, which repeatedly use seizures of high-grade dagga that is grown by specialist producers, who have access to capital, to justify spraying rural communities, the weed grown in the former Transkei is mostly cheap, and of poor quality.

“It’s ditch weed,” said one industry source. “This stuff sells in townships and at taxi ranks. None gets exported.”

Villagers say buyers sporadically hike into the valley to buy dagga. A recycled 1 litre yogurt container full of dagga sells for between R50 and R100.

Cynthia* (47) says she typically sells a full 30-litre plastic tub for R600, cutting her price to trade in bulk. It is the only cash she earns, and it supplements small social grants for three of her six children. The nearest grant pay point, along with the nearest school, hospital and shop, is two to three hours’ walk away.

“Kids leave home at four in the morning to reach school by seven,” she says. “When people fall ill, we carry them on wooden stretchers; the journey takes two days. Pregnant women walk to hospital to give birth.”

She is not married, she says, because the father of her children could not afford to pay lobola. “People don’t bother getting married here any more.”

At the river, three grandmothers dip enamel bowls into the water to fill their buckets before lifting them on to their heads for the walk back up to the village. A spring that supplied drinking water dried up in last year’s drought. Without piped water, residents drink directly from the river, and say that every year, children die of diarrhoea and are buried in the fields, amid the dagga bushes. Occasionally, a child gets taken to hospital in time, and survives.

They also have no electricity.

“The government doesn’t care about us,” says an old man. “They only send the helicopters with poison. They don’t offer ideas or projects after destroying our crops.”

He says he has been growing dagga for more than 40 years. Like everyone else, he professes never to have smoked the stuff, fearing it would make him “crazy”. More than 20 years ago, policemen rode in on horseback and caught him sleeping beside piles of dagga. “They beat me until I messed my pants,” he tells me, wheezing with inexplicable laughter.

He spent two years in jail and resumed dagga production upon returning home. Later, he moved to Durban to work in sugar cane plantations, but found the conditions too strict and the pay too low.

He still grows dagga.

“I feel bad doing this in front of the children, because I know it’s against the law, but what are my options?”

From the sky, his village is only a small patch of the Pondoland dagga-producing region, which extends over hundreds of square kilometres. To a helicopter pilot, this plantation represents a tiny fraction of an area that needs to be cleared. The old man tilts his head back and shuts his eyes against the sun.

“The police used to come and arrest us,” he says. “Now they fly in and poison our crops. Maybe that’s all that’s changed since 1994.”

*Not their real names

Publications

Publications

Partners

Partners