Everyone is feeling the pinch, but a deal that sounds too good to be true must be avoided at all costs, writes Mike McDougall

Faced with empty wallets and an increased cost of living, thousands of South Africans are placing their faith in get-rich-quick schemes, which lure desperate consumers with promises of unrealistic investment returns.

But whether it’s a Ponzi or a pyramid scheme, it can be mathematically proven that such schemes will eventually collapse and leave investors with nothing.

Ponzi and pyramid schemes are in essence the same thing – both rely on contributions from new investors to pay existing investors the promised returns. These are usually totally unrealistic and not comparable to returns achieved by legitimate savings and investment products.

While investors in a pyramid scheme know that they need to recruit new members to maintain the flow of funds, Ponzi schemes claim to make legitimate investments, but instead use the funds to enrich founders rather than use them for any legitimate business purposes.

It can be stated with absolute certainty that these schemes will eventually collapse, leaving many people financially destitute, while only the founders and a few early participants make considerable gains.

There are two reasons for this. Firstly, if a scheme is paying out more than is being earned, it will run out of money.

Secondly, such schemes constantly need new members to join in to sustain payments to existing members, and the reality is that they will ultimately run out of new investors.

The only uncertainty is when the collapse will happen, which depends on how quickly the fund is growing and how much bigger the declared yields are than the actual investment earnings on the funds invested.

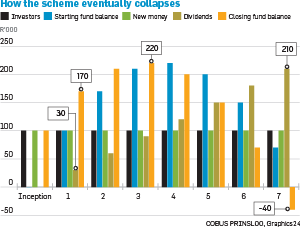

Say a scheme begins with 100 members, who each invest R1 000 with a promised return of 30% a month. Every month, 100 new members join the scheme and each invests the same amount.

Members receive their first payment the month after they make their investment. In this example, the scheme begins with 100 members and total funds of R100 000. In the second month, there are 200 members and the fund closes with R170 000 after paying dividends of R30 000 to the founding members.

The total dividends paid rapidly escalate each month as the membership base increases, until the scheme reaches its seventh month.

In its seventh month, the scheme begins with R70 000 and receives an additional R100 000 from new investors. However, the scheme must now pay total dividends of R210 000 to its members, leaving it R40 000 in debt.

Instead of R300, each investor only gets R243 and the scheme collapses.

With more rapid growth in members or lower payouts, the scheme would continue for longer, but the result would ultimately be the same.

As pyramid schemes rely on snaring new members, you should be wary of being dazzled by stories of high returns by people already in a scheme.

The reality is that by the time you join a scheme, you may just be propping the scheme up so that early joiners can profit at your expense.

You and other new investors may never recoup even your initial capital amount, let alone make a return on your investment.

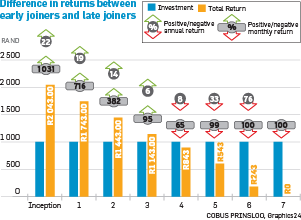

DIFFERENCE IN RETURNS BETWEEN EARLY JOINERS AND LATE JOINERS

If you were a member who entered the scheme at its inception with an investment of R1 000, you would have earned total returns of R2 043 by the seventh month, when the scheme fails. This means that your return would have totalled an overwhelming 22% a month.

However, if you had only joined the scheme in its sixth month, you would only have earned R243 back on your investment, representing a loss of 76%. If you had entered in the seventh month as the scheme collapsed, you would have lost your entire investment.

Those entering the scheme early can therefore make spectacular returns despite losing all their capital, while those joining later lose money. It’s a classic example of robbing Peter to pay Paul.

The people who get in early are usually the founders of the scheme and those close to them.

McDougall is CEO of the Actuarial Society of SA

Before entering into an investment or making an ‘online donation’ with the hope of high returns, ask the following questions:

1. How are returns generated?

Legitimate investment schemes are transparent. You should be able to understand the underlying assets. Even when derivative structures are used, you should be given enough information to understand your risks and potential returns.

2. How aggressively are you being pursued to join?

Legitimate investment schemes generate returns from invested assets, but fraudulent schemes rely heavily on funds from new members to pay existing members.

3. How do returns compare with other similar products?

If returns are unusually high, be very cautious.

4. How is the scheme regulated and audited?

Publications

Publications

Partners

Partners