Who is Zoë Wicomb – and why do more local readers not know the work of one of the country’s most revered authors? PhD literature candidate Manosa Nthunya offers an introduction to this stunning post-apartheid feminist voice that centres on ordinary lives.

I will never forget the first time I encountered the work of Zoë Wicomb.

I was a third-year student taking a course on post-apartheid writing at Rhodes University. We had just finished reading Ivan Vladislavic’s The Exploded View and I was still astonished by this writer’s originality.

Although at first a challenging read, when I started to see a thematic connection between the four stories in his book and what that said about the haunted post-apartheid city, I went through an incredibly unique reading experience.

Having moved from Johannesburg to study at the institution, Vladislavic’s work took me back to Jozi – a place I regard as home – as he provided many references that are emblematic of the city.

After enjoying this book and attending the lectures on it, I did not think it could get better. The next book on the reading list was Zoë Wicomb’s David’s Story, an author I had not heard of even though I considered myself relatively well read in South African literature.

A week before the lectures on the novel I attempted to read it but couldn’t even get past the preface.

I simply could not comprehend what was being said and, that being the case, looked forward to some form of assistance on how I might approach the book. The lecturer conceded to this difficulty – something that most literature students appreciate lest their intellect be damned, especially at third-year level.

How, then, does one read the book, a student asked. With literature, the lecturer responded, what always helps – in fact what is required from the reader – is that they read again and again.

Not one to shy away from challenges, I was adamant to reread David’s Story several times until I understood what it meant. Since then, 2012, until now, 2019, I have been reading Wicomb’s work trying to understand its forms, subject matters and what it says about the post-apartheid South African space.

The life and times

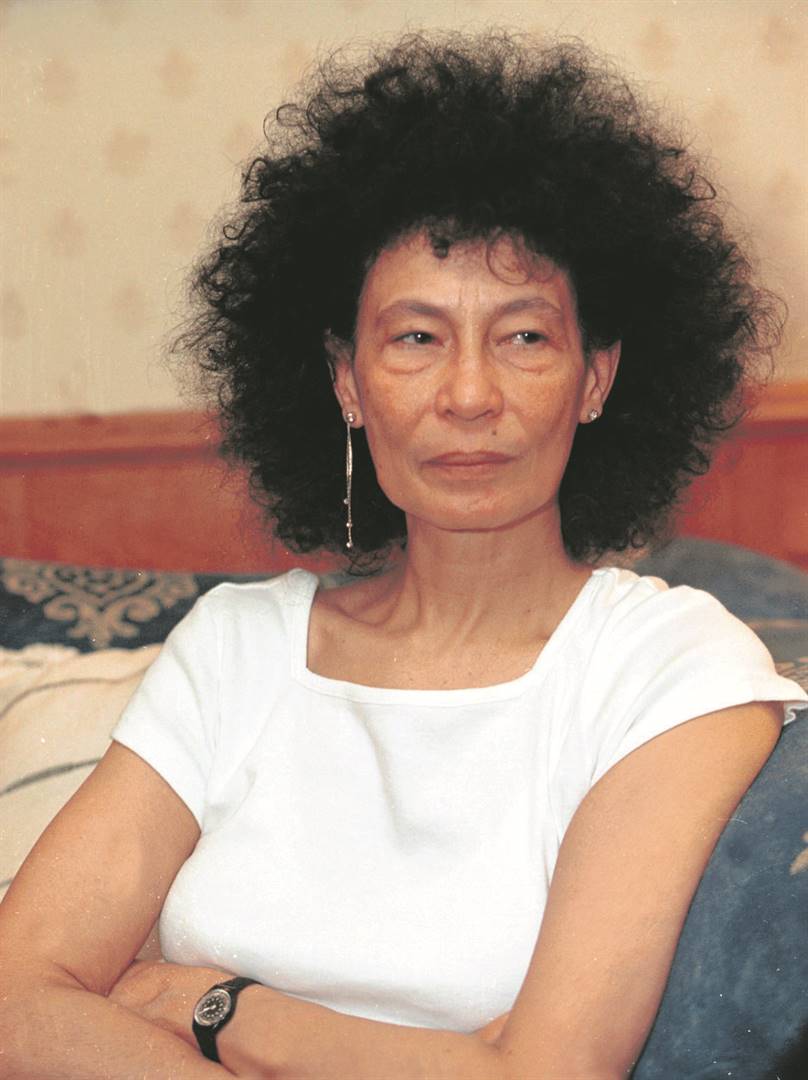

Wicomb was born in the Western Cape in 1948 and grew up in a small town in Namaqualand.

She has said that as a child there was very little reading material at her home except for the Children’s Bible, Jane Austen’s Pride and Prejudice and an abridged copy of Charles Dicken’s David Copperfield.

A keen reader, after high school she studied English at the University of the Western Cape, a university, at that time, that was reserved for coloured students. Wicomb has said she received a very poor literary education at the institution which, judging by the times, is not hard to believe.

After graduating she left South Africa for England in 1970 as she could not bear to live in the country’s tumultuous political climate. Political parties had been banned and it seemed there was no way out of apartheid.

Little did Wicomb know, as she would recall later, that the Black Consciousness Movement was already gaining momentum and she says that had she known this: “I would not have felt so despondent and anxious to get away.”

Wicomb furthered her education while remaining involved in anti-apartheid work and would eventually settle in Glasgow, in Scotland.

Finding David

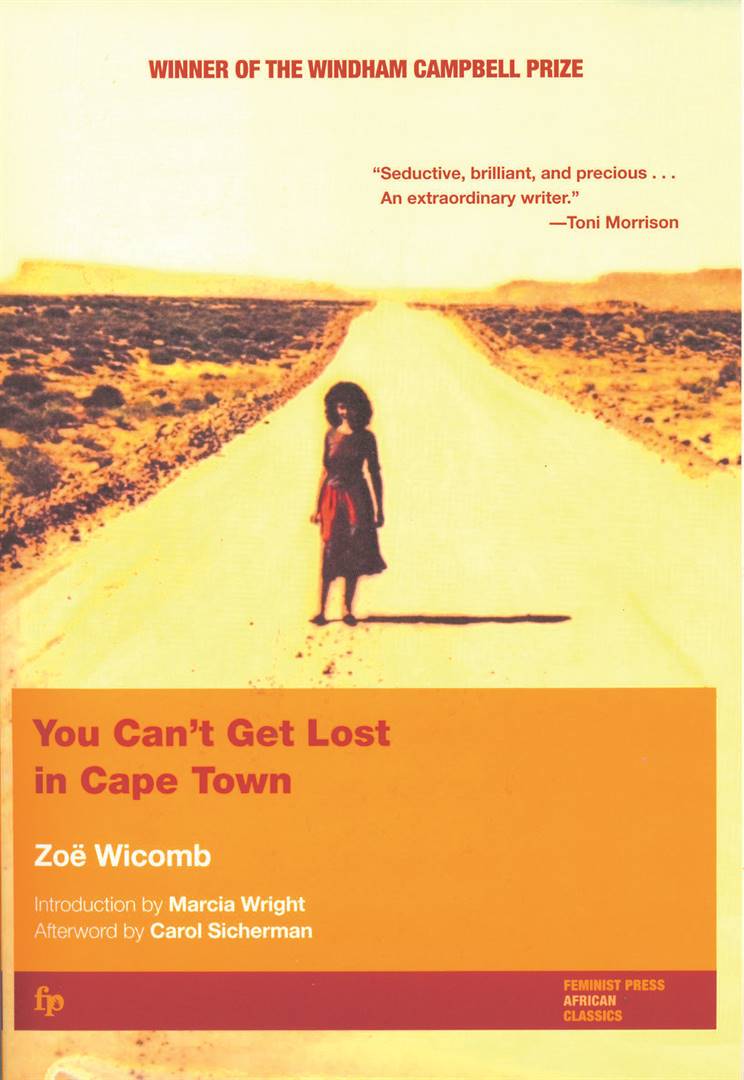

In 1987 she released her first linked stories, You Can’t Get Lost in Cape Town, to great acclaim. The short stories are set in the Western Cape in Namaqualand and follow the life of its female protagonist, Frieda Shenton.

Frieda comes from a family where she is taught to resent her home language, Afrikaans, and is consistently told to speak English and straighten her hair as that is what is seen as respectable in her community.

The short stories interrogate what it means to have lived as coloured under apartheid and the shame that apartheid ideology attached to this identity.

Importantly, this collection, similar to Wicomb’s later fictions, was already attentive to showing the repercussions of a patriarchal world and how destructive it has been for women.

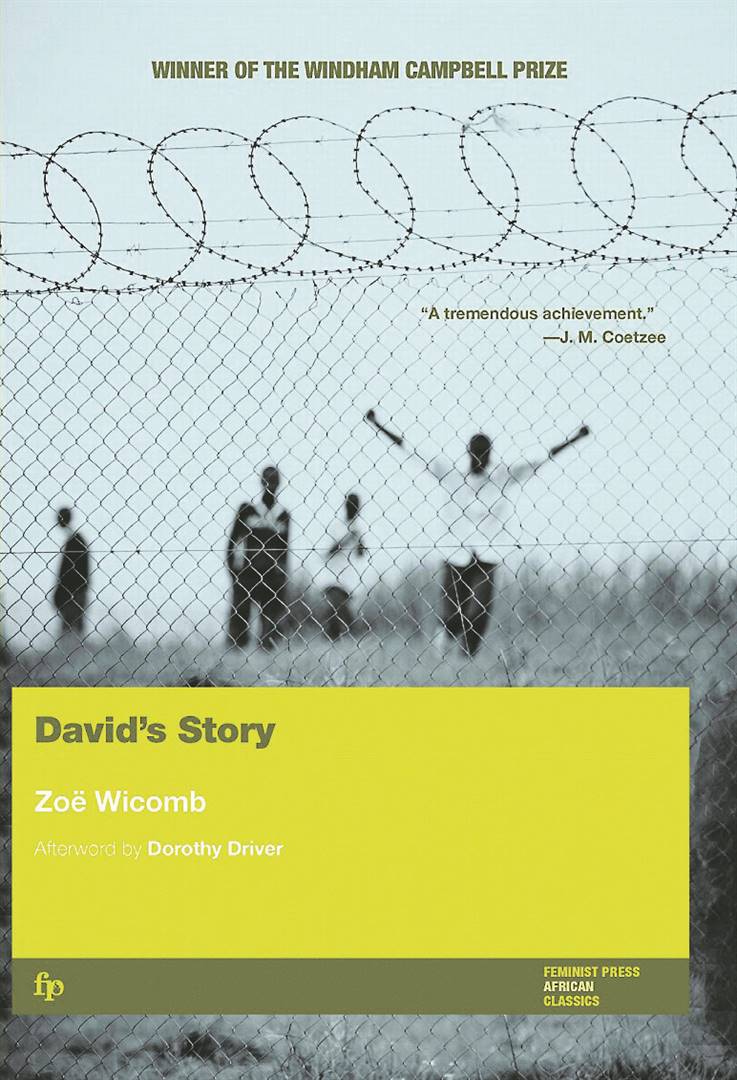

Wicomb’s follow-up fiction was her ground-breaking novel, David’s Story, published in 2000, the one that was giving me all the trouble.

In this novel we follow the life of David Dirkse, a member of Umkhonto weSizwe, the armed wing of the ANC. The novel unfolds in the early 1990s at the time of Nelson Mandela’s release from prison.

David, having struggled with his coloured identity in the liberation organisation and coming from a family that disparages the fact that he is part of a revolutionary movement, attempts to uncover his racial history, hoping to find a better understanding of where he comes from and what kind of life will be possible for him in post-apartheid South Africa.

But what he finds, contrary to his expectations, is that there is no reliable history that can definitively tell him about his past.

The novel therefore suggests that, despite apartheid’s attempt to make us believe that we have “pure” blood that designates us into different racial or ethnic identities, the past is in fact very messy and entangled.

David’s Story shows how identities are constructed by power and how attempting to cling strongly to a racial or ethnic identity is in fact to give in to the language of the dominant.

This does not mean, of course, that we do not suffer because of these racial categories; we certainly do and in all her fictions Wicomb shows how damaging this is, especially for ordinary people.

The power of the everyday

Wicomb’s focus on ordinary lives resonates with Njabulo S Ndebele’s call for the “rediscovery of the ordinary” where he argued, as early as the 1980s, that post-apartheid South African writing would need to move away from the spectacular writing that characterised protest literature (as necessary as it was) and rather embrace and communicate people’s common emotional experiences.

It is here, Ndebele argued, that qualities such as resilience, vulnerability and the tremendous abilities of the imagination of black people will be seen.

Wicomb has produced more works of fiction which include a collection of short stories, The One That Got Away (2008); two novels, Playing in the Light (2006); and October (2014).

What permeates all these fictional works is the importance of reckoning with history and its attendant ironies.

In other words, this is a history that is not linear and therefore not easily comprehensible; it takes on many contours and is never directly visible. What we can’t do is escape it.

What is, however, possible in all Wicomb’s fictions are different ways of looking at it, ways that might even surprise us and create different forms of understanding of what it means to be in the world.

Wicomb has received praise from acclaimed writers, such as the recipient of the Nobel Prize for Literature, Toni Morrison, who has said that she’s an “extraordinary writer … seductive, brilliant, and precious, her talent glitters”.

On publication of David’s Story, JM Coetzee, another Nobel Laureate for Literature, said: “For years we have been waiting to see what the literature of post-apartheid South Africa will look like.

Now Zoë Wicomb delivers the goods. Witty in tone, sophisticated in technique, eclectic in language, beholden to no one in its politics, David’s Story is a tremendous achievement and a huge step in the remaking of the South African novel.”

It is without doubt that Wicomb enjoys the same status that South African writers – such as Mandla Langa, Nadine Gordimer, K Sello Duiker, Lewis Nkosi, Antjie Krog, Miriam Tlali, Phaswane Mpe, Zakes Mda, Bessie Head, Vladislavic, Ndebele, Coetzee – have on reflecting on South African life.

The Wicomb challenge

But Wicomb, despite the acclaims she has received and honorary degrees conferred, including from the University of Cape Town and the University of Pretoria, is still relatively unknown in the country where she was born, except in literature departments where her work is taught.

Part of the reason for this, I suspect, is that Wicomb has said that she has a fear of speaking in public and this has prevented her from giving interviews and therefore, perhaps, being better known.

But then all of this seems unnecessary because we do have her fictional works and a newly published collection of her essays on South African literature and culture entitled Race, Nation, Translation: South African Essays, 1990 – 2013.

If it is the case, as history has thus far proved, that fictional works live far longer than we mortal creatures do, then I have no doubt that Wicomb’s work is going to be critical to how South African writing develops in years to come.

We are therefore lucky to have a writer of Wicomb’s stature reflecting on our history and present conditions with unmatched depth and skill. She asks difficult questions and confronts the world with brute honesty.

If, seven years ago, when I walked into my South African literature class, I did not know how to read this writer, it is the case now, having read her work countless times, that I have also been challenged to think more critically about the space in which I find myself, in this country and the world.

South Africa’s history continues to have a profound effect on its landscape as we seem more polarised than we have been in our democratic dispensation; a polarisation, evidently, that is a consequence of people’s material lives not having changed and a now obvious and accepted disillusionment with the promises of 1994.

Our friendships, the people we date, and the communities we come from continue to reflect this historical division.

However, what we learn from writers and thinkers such as Wicomb is that it is important to reflect on the processes that make us who we are, lest we fall prey to the easy, dominant ideologies that ceaselessly compete for our attention.

It is not so much that deep, contemplative thinking – or finally being a competent reader – will do away with history or the socio-economic structures it has set in place.

But the power of fiction, when done well, is that it troubles our social reading habits and how they inform our relations to others.

It is here that possibilities for the ethical, however perilous or almost impossible, become imaginatively opened to the reader.

Publications

Publications

Partners

Partners