NAF/Basa Arts Journalist of the Year Lwandile Fikeni chooses Zanele Muholi as #Trending’s photographer of the year. He reviews her latest exhibition

Somnyama Ngonyama by Zanele Muholi at Stevenson, Johannesburg

Rating: 4/5

“We have lost a lot of people because of hate crimes ... You never know if you’re going to see this person again the following day,” says Zanele Muholi about Brave Beauties, her new, growing series of queer portraits. As with her series Faces and Phases, it is, in many ways, a protest against how the status quo marginalises and subjugates certain identities to make them its subclass.

In her new exhibition, Somnyama Ngonyama, Muholi responds to a number of other issues, which intersect, even uncomfortably, with the work she is known for. These issues are rendered with the same urgency: the placid, solemn faces that look you straight in the eye.

The effect is not only that you are gazing into the lives of her subjects, but that her subjects are aware of you, and there is a reciprocated knowing. It exchanges the position of subject and viewer, which lends it its poignancy: that it is not queerness from without but our own queerness from within that we must acknowledge as not Other, but as Same within our peculiar humanness to be any possible human variation there is.

For me, her images have a neutralising effect by not objectifying “deviant” sexuality, but bringing us closer to our innate queerness and averting the fear of being intimidated by what we find in the mirror when we’re alone.

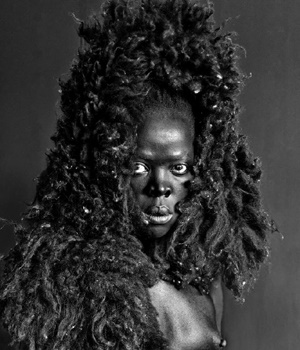

A laminated, larger-than-life image hangs on the wall to your left as you make your way to the reception area at Stevenson. It is a self-portrait of Muholi in what appears to be sheared black sheepskin draped around her head to give the illusion of an overgrown coif. A breast is in full view.

“You see a lot of nipple. I grew up in KZN. I’m Zulu,” she says. “Where I come from, a breast is a common point of your visual space. It is not sexual.” The portrait is unforgettable and almost haunting, with the added, heightened dramatic effect of the image having been drained of light, making its blackness appear to project light from within.

“I don’t paint myself black, because I’m black anyways,” she says. The images are computer manipulated to alter the contrast and bring out the melanin buried in her skin, pouring it out on to the surface like a thick, slick, oily blackness. The piece relates to the pencil test of apartheid in the 60s and 70s. A government bureaucrat would stick the pencil in your hair and if it stuck, then it proved your blackness. It was a violent act of Othering human beings to subjugate them.

The choice to use her body as a site of critique is a move away from using her friends in portraits. Aesthetically, the images are menacing and the allusion to blackface is highly troubling. If the earlier work read as the dignified resistance of an artist who felt (and still does) the need to document Othered identities, then Somnyama Ngonyama reveals a ferocity behind that placid work. It alludes to the frustration, the anger, the disappointments that come with dedicating yourself to a country that wants to kill you in nearly every corner for reasons you can’t change even if you tried: you’re a woman; you’re queer; you’re black.

The sheared black sheepskin suggests she is the black sheep of her family.

“It doesn’t matter how useless your straight brother can be ... because he can have children, your mother and father will still respect him more,” she says.

“Queer allergies start from our families before we even face the world out there. In short, I cannot divorce my queer self from the person I am. Everything I do becomes the visual politic of who I am.”

Brave Beauties, on the other hand, is more classic Muholi. The portraits are of black trans women and/or feminine gay men. The project was inspired by traditional magazine covers.

“I was thinking: would South Africa as a democratic country have an image of a trans woman as the cover of a magazine?” She pauses. “I want to see 100% visibly for the queer community in this country as a way of challenging these phobias.”

It was upon seeing Caitlyn Jenner on the cover of Vanity Fair that the idea crystallised.

“We need to build our own archives.”

Her work takes as its subject the importance of history and memory. “The name and surname in each portrait is significant. These girls enter beauty pageants to change mind-sets in the communities where they live, the same communities where they are most likely to be harassed, or worse, which is why I call them brave beauties,” says the artist.

The exhibition is on at Stevenson in Braamfontein until December 19 and again from January 4 to 29

Publications

Publications

Partners

Partners