At just 26, Nick Mulgrew’s writing shows an awareness and humour far beyond his years. We find out how he gets into the minds of his characters

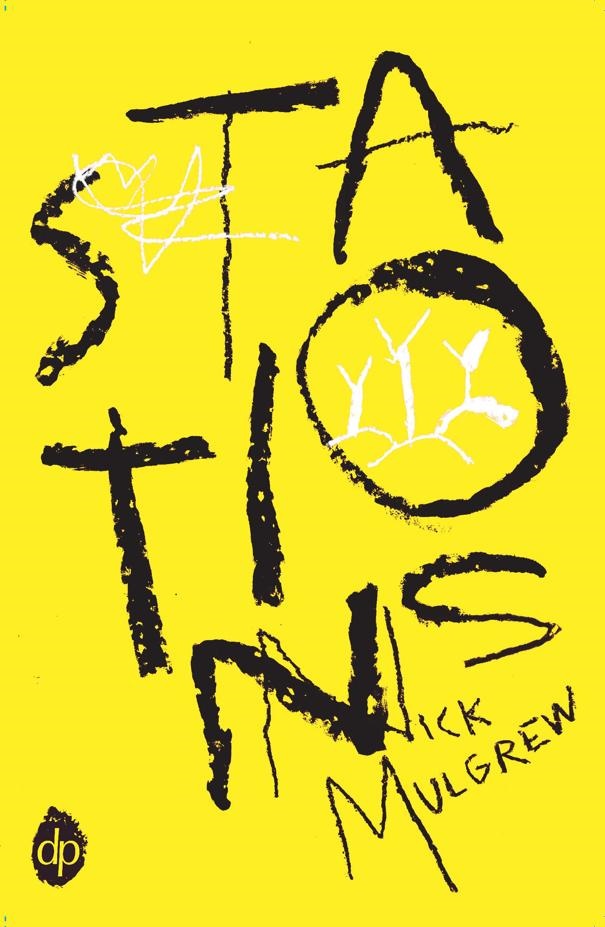

You can open journalist, editor and indie publisher Nick Mulgrew’s Stationsat any page, choose a paragraph, and within seconds find yourself drawn into his world of considerate, complex and sincere characters.

Throughout the series of 14 short stories in Stations, Mulgrew’s debut prose anthology, your imagination will get caught in the poetic tumbles he weaves through everyday moments of South African life, leaving you feeling blind for not having noticed them before.

If you’re unfamiliar with Mulgrew’s fictional writings, this is to be expected.

As a poet, he is fairly well known, but it is his editorial work over the past few years that has captured the attention of a younger audience hungry for the sort of unique subjects he uncovers and explores.

You could find them inside The Myth of This is that We’re All in this Together – his first book of poetry – or the works of his two publishing projects called the Prufrock Literary Magazine and uHlanga, “a progressive poetry press”.

They’re also in his regular newspaper columns exploring the complex life of beer drinkers, features on the cultural appropriation of Spur restaurants, lengthy and insightful profiles on unknown South African heroes, and book reviews that will make you want to be a published novelist.

Imagine my shock last week when I learnt that Mulgrew was only 26; yet, he employs literary maturity usually seen in more experienced writers.

I needed to know just what compels his insatiable writing and how he gets into the minds of his characters, so I sat down with him at the National Arts Festival in Grahamstown, where he was co-editing the Cue daily newspaper for the festival.

There’s a great character in one of the stories in your book called Nandi. How did you – as a white man – try to write the story of a black woman from the townships?

With that story in particular, it was a story communicated to me through a friend.

The characters I imagine who are different to me are not just imaginings, but are normally stories that are related to me by other people that I then synthesise.

But I very rarely make characters who are not like me. It’s a way of protecting myself and my readers from a sort of psychic violence.

That kind of experience of entering the body of another person always tends to be problematic, but that’s always what you’re dealing with as a fiction writer.

What matters is to be sensitive about your consciousness and make sure the micro-violations are made worthwhile by the moral or aesthetic value of the work you produce.

A lot of the time, its just about having conversations and asking: ‘Does this seem real?’ If it seems real, it’s acceptable.

What is it like to be a white writer in South Africa at the moment?

It’s a tough position – a privileged position, but a tough one. Khaya Dlanga recently wrote that the black writer is the least marketable writer in South Africa, and he’s completely right about that.

So I’m not going to say being a white writer is difficult, because it isn’t, not compared with being a black writer in South Africa.

The conservative South African publishing industry privileges people like me who are first-language English, conventional English, who have the connections – like I do – who are more likely to fall into “lucky” situations, as I have.

When I say luck, I mean privilege a lot of the time.

Without an awareness of that, your writing is going to be toxic, and your work is going to be toxic.

For me, the feeling is much more urgent to help lay some conditions for a kind of working, an inclusivity and openness that can help change the literary landscape.

As far as my writing goes, I can’t pretend to write as anything other than what I am: a white, straight, cisgendered man.

I can’t pretend to know what it’s like to be anybody else. I think that’s going to be the hallmark of all good South African writing from now on – the knowledge of your position, a kind of unapologetic self-awareness, an understanding of your faults, your foibles, the things that predicate your identity, no matter how unpleasant they may be; no matter how much you have to confront yourself.

It’s an emotionally exhausting thing, but I think that’s the price you have to pay.

What would these conditions be?

I don’t want to be prescriptive, but if I were giving advice, I would say maybe not be an arsehole as much as possible.

Obviously, to completely mitigate your risk of not hurting people and being problematic, then don’t write at all, but if you really want to continue, then have as many conversations with people as possible. You can’t exist on your own.

Make yourself as uncomfortable as possible. It sounds self-flagellating, but it isn’t. You can’t just be someone who thinks you can do whatever you want, all the time, under every condition – as white writers thought they could do for a very long time.

There are enough resources for male writers, straight writers, white writers – or any kind of writer actually – to educate themselves and become sensitive.

Sensitivity is a great marker of writing, and it’s now just another layer of sensitivity that writers have to work with, just another part of self-education. It’s really not that difficult to care, and that’s really what it comes down to.

You’re fighting for a poetry that isn’t spoken. Do you ever feel like you’re on the losing end of the publishing battle?

I wouldn’t say it’s losing, but it’s maybe a more liminal space. The majority of poetry in South Africa is spoken, but not in terms of just readings such as Kholeka Phutuma’s work.

It’s just knowing the limits of my ambition. It’s not to fight for the rights of read poetry or poetry on the page.

I believe written and spoken poetry exist in the same space, but right now it’s about reimagining its boundaries.

It doesn’t matter that a huge number of people are clamouring to get the works – it’s just adding to the space, like mulch and more mulch. It’s just something I want to do.

Publications

Publications

Partners

Partners