From communist revolutionaries to controversial strippers, queens of pop to cold-blooded killers, Maverick, the first book from novelist Lauren Beukes, profiles SA’s most famous (or infamous) women in history. A second edition has been released, co-authored by Nechama Brodie, and includes new chapters on Cissie Gool, Eudy Simelane and, in an edited extract below, former minister of health Manto Tshabalala-Msimang

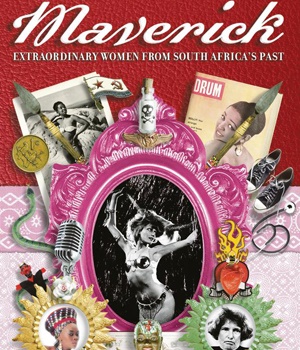

Maverick: Extraordinary women from South Africa’s past

by Lauren Beukes and Nechama Brodie

Umuzi

272 pages

R220

In December 2009, in Johannesburg’s exclusive Donald Gordon Medical Centre, a woman lay dying. There may well have been the backbeat of life-support machines – she was in the ICU after all – and there was certainly a heavy media presence, enough that security guards were posted at the door to her room. But this was no Brenda Fassie. While the bed’s occupant was undoubtedly one of the most notorious women in South Africa, there were no legions of fans praying for her recovery.

In fact, if people were praying at all, it might have been for things to go the other way. Which sounds like a perfectly horrible thing to say, but then again, no one really expects polite condolences for a mass murderer.

Between June 1999 and September 2008, the woman in the hospital bed had been responsible for an estimated 330 000 preventable deaths.

What made the incomprehensible figure worse was that she was no arbitrary murderess, not even a Daisy de Melker. She had been the minister of health.

Under her watch, just as the HIV epidemic was at its peak of expansion in South Africa, the government had pulled back its antiretroviral (ARV) programme, instead advocating a discredited solvent, Virodene, and promoting a supposedly curative diet of beetroot, African potato, olive oil, garlic and lemon. Without effective treatment, hundreds of thousands of South Africans died. Pregnant women were denied access to the drugs that would have prevented transmission of the virus from mother to child, resulting in 35 000 infants being born with HIV.

Faced with international calls for her resignation, the health minister stubbornly refused to back down from her policies, or even to publicly admit that HIV caused Aids. There were rumours of some sort of Faustian pact between the minister and the then state president Thabo Mbeki, both former exiles, both apparently, mysteriously, beholden to a group of lunatic fringe Aids denialists. The government, in turn, responded by blaming pharmaceutical companies for driving their own agenda. Conspiracy theories abounded. People kept on dying.

When, shortly before 3pm on 16 December 2009, 69-year-old Dr Manto Tshabalala-Msimang (also known, rather un-fondly, as ‘Dr Beetroot’) finally passed away from complications arising from a liver transplant two years earlier, the ruling African National Congress elided the controversy and eulogised her as an undisputed struggle hero. The press was less nostalgic.

Although there were whispers that shortly before her death, Manto had been ready to admit to her mistakes, her progressively poor health prevented her from making any such public statement.

History would remember her as one of the greatest villains of post-apartheid South Africa.

...

In 1990, Manto returned to South Africa, along with thousands of other exiles. She was elected to Parliament in the country’s first democratic elections in 1994, and chaired the National Assembly’s health committee, before being appointed as deputy minister of justice in 1996.

Up to that point, there was little to indicate that the deputy minister was anything more than a diligent official, reaping the hard-earned rewards of an extensive education and decades of devoted public and party service. Manto had even been part of the Government of National Unity team that had drafted the country’s first, comprehensive and progressive, Aids-response plan, together with Dr Nkosazana Dlamini-Zuma, who would go on to become the first minister of health.

Signs of trouble began to emerge as early as 1997 when Dlamini-Zuma and then deputy president Thabo Mbeki tried to force the Medicines Control Council (MCC) to approve the trial of a new supposed miracle cure for Aids – a freezing solution called Virodene, which was being touted by husband-and-wife team Zigi and Olga Visser.

The MCC rejected the Vissers’ claims and refused to allow the trials, which prompted the health minister to remove several senior MCC officials, including the chairperson, and replace them with candidates thought to be more sympathetic to the government. The new council was an equal disappointment, again refusing to endorse Virodene. The drug was eventually tested on soldiers in Tanzania, apparently with financial support from the ANC. Certainly, Manto managed to pay the clinic a visit on one of her trips to the country she described as her ‘second home’.

...

When, in 1999, he took over as president of South Africa – Nelson Mandela having declined to run for a second term – Mbeki’s madness was given free rein. He set up a Presidential Aids Advisory Panel, of which at least half were Aids denialists. Under this, and subsequent councils, a national HIV/Aids response strategy was developed that focused on prevention and support – teaching life skills to children, promoting safer sex, providing home-based care for those living with and affected by HIV/Aids – but which, noticeably, declined to make any provision for actual treatment using ARVs. Even as new infections and HIV-related deaths continued to rise, Mbeki remained unwavering, famously telling a gathering of international scientists in Durban that poverty, rather than HIV, caused Aids.

By October 2000, Mbeki’s stance had become so controversial that he largely withdrew from making public comments about Aids, instead handing the cudgels of denial over to his trusted comrade in exile, Dr Manto Tshabalala-Msimang, whom he had appointed as health minister shortly after his election in 1999.

While Mbeki and Manto had been getting their quacks in a row, the battle over treatment for HIV had been waging on several other fronts – most notably, a successful legal campaign to produce and procure cheaper generic ARVs in South Africa. But even then, the government refused to make the life-saving drugs available.

In 2001, the Treatment Action Campaign took legal action against the health minister, demanding the provision of ARVs for the prevention of mother-to-child transmission.

When, the following year, the Constitutional Court handed down a judgment instructing the minister to provide Nevirapine to pregnant mothers, Manto complained that she was being forced to ‘poison’ her people.

It would take another two years before, slowly and grudgingly, the health department began to roll out ARV treatment.

. Beukes’ latest novel, Broken Monsters, will be launched in Joburg on November 26 by way of a Broken Monsters Charity Art Show. More than 120 local artists have customised pages from the book for sale at R1 500 each. All proceeds will go to local children’s literacy project Book Dash. The event is at 10A Victoria Road, Lorentzville, Joburg, and will start at 6pm

Publications

Publications

Partners

Partners