Ronnie Kasrils’ initial impression of Jacob Zuma, upon meeting during their years of exile in the 1980s, is far removed from the one he presently holds; he remembers Zuma as an engaging, pleasant man; “a well-dressed activist”.

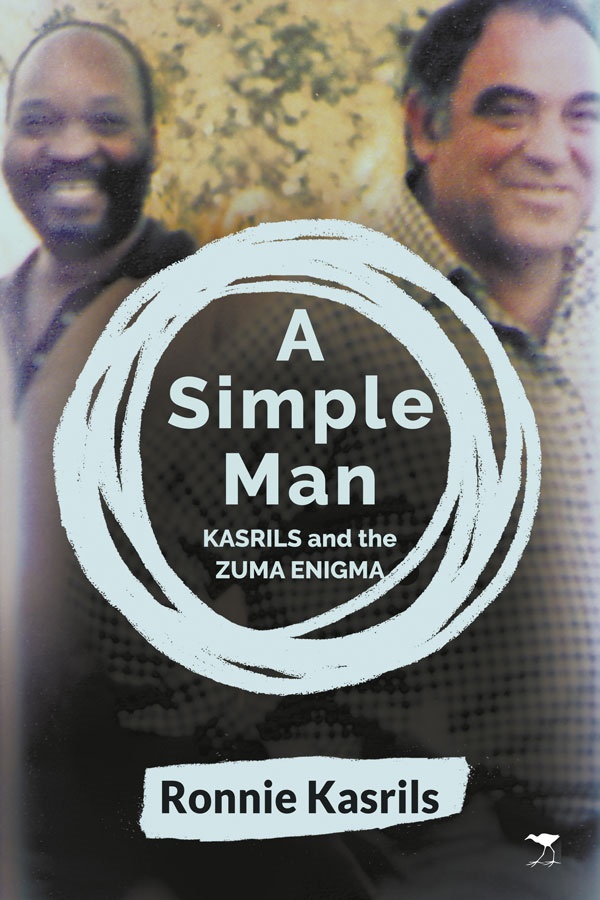

In this extract from his book A Simple Man, Kasrils – who was commander in Umkhonto weSizwe from its inception in 1961 until 1990, and served in government from 1994 to his resignation as minister for intelligence in 2008 – describes how, despite its current leader, the transformation of an economy and society is possible given the people’s involvement

A People’s Pact

The enigmatic Jacob Zuma is not the simple man of the people he enjoys portraying himself as. Astute and engaging from earlier days, along the way he has become driven by a lust for wealth and power.

Whether he was lured by the unscrupulous or was the principal in engagement himself is a moot point.

Jacob Zuma – and the Gupta state-capture project – is a consequence of the economic choices made by the Faustian pact. He and many others have exploited the opportunities presented by the new form of sociopolitical relationships, emerging after the demise

of apartheid, that favour predatory forces.

The economic failures that arose as a result of the settlement, the collapse of revolutionary resolve, have allowed a pack of criminals and charlatans to hijack the ANC and masquerade as the proponents of radical economic transformation, which is a term they abuse to hide their nefarious business interests.

They look like tin-pot Mussolinis strutting the stage in a comic opera but they are as dangerous as any brand of Duce (“leader”), from Idi Amin and Mobutu to Pinochet. They have considerable resources at their disposal and are able to wield influence within the security and intelligence services. All this emerges from a vacuum of leadership and from economic failure. Jacob Zuma has adroitly used the collapse of the ANC’s revolutionary agenda as a stepping stone for his own goals.

The danger that all this poses to the ANC and to the country was highlighted by Blade Nzimande in his opening address to the South African Communist Party’s national congress in July 2017. He said: “It is an open secret … the ANC is threatened with serious decline, buffeted as it is by factionalism, moneyed patronage networks, and corporate capture … If the current trajectory is not reversed, the ANC is unlikely to pass the 50% mark in the general elections scheduled for 2019 … Much, but not all, of this popular decline is related to the almost daily revelations of scandals involving highly placed ANC politicians in government and particularly those who have been entangled within the notorious Gupta empire, including the president’s own family. The phenomenon of ‘state capture’ of critical and sensitive state organs and state-owned enterprises by a web of parasitic capitalists has created a parallel, shadow state, or even, as some leading academics have argued, a ‘silent coup’.”

Given my 2005 critique of Zuma to the SACP leadership, I listened as Nzimande confessed to the “marriage of convenience” that had been formed to topple [Thabo] Mbeki and replace him with Zuma. He bitterly added: “Our trust has been broken and we have been betrayed”.

I could take no joy in that. The situation was far too dire.

The fact that Zuma’s term as the country’s president is due to end with the national elections of 2019 – leaving aside the thought of some form of disguised coup to extend his term in office – does not mean the end of the nightmare. He is working night and day to ensure his dynasty is maintained, that whoever takes over – whether his faction or another – will keep him out of prison, that the shadow state he has established will continue to manipulate power on his behalf and multiply his wealth. He might even manoeuvre for a third term as ANC president.

“It was inevitable that it would get to this point. The great unravelling, the lacuna, the interregnum between one epoch and the next. Now is the time that all the president’s men and women – those shifted into place since 2009 (and before) and who have survived and still lurk in the shadows – prepare to launch their final offensive to protect Jacob Zuma,” warns the journalist Marianne Thamm.

Either way, Zuma or no Zuma, unless we reverse the Faustian pact that has made his rise to power possible, those “treacherous decisions” of the early 1990s – as Sampie Terreblanche has termed them – will “haunt South Africa for generations to come”.

A cornered Zuma cries “havoc” and, if he can get away with it, would “let slip the dogs of war”. Reasons, incidents and frame-ups can be manufactured. If we allow the far-from-simple man and his cabal to win, then beware the apocalypse.

Our benighted world faces the consequences of interminable, overlapping deals with the devil. International monopoly capitalism is wreaking unprecedented havoc in the quest for markets and resources, with invasion, war, destruction and reaction in its wake. As was stated a century ago by Rosa Luxemburg during a previous era of havoc, “the outcome is either socialism or barbarism”.

The consequences today, including the ravages of pollution and climate change, threaten humanity and countless other species and the very capacity of our planet to maintain life as we know it.

Our people have suffered the consequences of decisions and tradeoffs made by the political and economic elites, at home and abroad, who believe they know what is best for the masses. Those decisions have protected big business interests, devastated the lives of the workers, the poor, the unemployed, the rural, the women, youth, the marginalised; adversely affected land, water, food security and the environment.

Bad policies caused the rise of unprecedented unemployment (35% counting those who have given up looking), inequality, crime, corruption, violence and xenophobia. The result has crippled the country’s economy, undermined our democracy and benefited the extremely wealthy.

We are not alone, for when we look at the world’s most powerful country, the United States of America, we are reminded of Marx’s observation about state capture: government is the executive committee of the bourgeoisie. We witness a worldwide phenomenon, which has seen 1% of humanity hogging 50% of wealth and running governments in their interests. Periodic financial chaos and bouts of austerity, worsening unemployment as a “Fourth Industrial Revolution” threatens the majority of jobs, as well as growing evidence of climate meltdown, all reflect the irrational, self-destructive character of global capitalism.

In South Africa as we struggle with the consequences of disastrous errors and deals, the demagogic cries for radical economic transformation are hollow calls from a small rank of crony capitalists headed by the Zuptas, besotted by their own greedy interests, who do not state how their mantra is to benefit the majority. But likewise, the traditional capitalist elite have no answer to the claim that they refuse to invest more than a trillion in idle cash, and overpay their executives to the point that three white men now have as much wealth as half the 56 million population.

What is required to avert catastrophe is a pact, a People’s Pact, to be arrived at through a national consultative process built from grassroots participation. No community or section of the people must be ignored in order to give democratic expression to the will of all who yearn for security and comfort. We have an example of such mobilisation in the Congress of the People, of 1955, which gave rise to the Freedom Charter. The 1992–94 Reconstruction and Development Programme process, similarly, gathered inputs from the Mass Democratic Movement and generated a popular programme based on decades of struggle demands.

Today we have a parliamentary democracy, resulting from that vision of liberation, which must be a part of the process of re-inventing true people’s power through ground-up participation, which rose to heights during the 1980s in the form of the UDF and mass democratic movement. Today’s polity, from municipal to national level, must be transformed by a system of direct accountability to the electorate with elected representatives subject to recall by their constituency rather than being rubber-stamp captives of a party list. Such measures must focus on a new beginning required to save our country from endemic crisis.

Tackling the economy must be fundamental to the solution. Which is why the approach must place the interests of the people before profits, and focus on the needs of the poor in order to eradicate poverty and unemployment. This will require turning away from the prescripts of a corporate-dominated economy, which have been disastrous. We could start by revisiting the product of the MERG group and subjecting their recommendations to consideration and debate.

Vital to economic turn-around and the growth required to create decent jobs for all and an effective industrial policy is to stem the flow of capital abroad and unlock the dormant billions of rand within the country. Increasing the corporate tax rate, which benefitted from the generosity of the cuts allowed since 1994, would create further funds for social and infrastructural investment, and for example provide for free university education for needy students and the long-delayed National Health Insurance. It is shocking that a poor woman is expected to rear the next generation on a meagre child support grant of R380 a month, with even the Democratic Alliance agreeing it should be doubled. It is as shocking as the Marikana deaths that upward of 100 mentally incapacitated patients should die because the Gauteng medical service had to outsource them into inadequate private care facilities where they were grossly neglected.

We do not have to believe that the only way to develop the economy is through bowing to elusive foreign investment and taking more foreign debt – since at $150 billion, we are over-borrowed to international financiers. (Some such loans, such as borrowed by Eskom and Transnet for corrupt projects, could technically be considered “Odious Debt” and repudiated.) We have the resources, mineral and other, that must be utilised for economic and social development.

Our human resource, the talent and energy of our people, must be fully realised and not left dormant. Cuba provides the example of how it eradicated illiteracy within one year in 1961, shortly after its revolution, by mobilising 200 000 students and teachers to fulfil the task, and how after the Soviet Union’s patronage it moved to a relatively post-carbon economy. Its resources compared to ours are minimal apart from the turning of human resource into the most powerful weapons of change and development.

The blight of corruption can only be effectively tackled by transparency and competency in government, democratic controls and the involvement of an active civil society, which must be built and preserved as a necessary oversight watchdog of the state, public and private enterprises, and security agencies. That active civil society is integral to all the struggles and challenges we face and has served us well in the past. Instead of searching for so-called “best practice” solutions from business practitioners and pricy consultants we are able to draw on the creativity of people’s power from the examples of history.

The transformation of an economy and society is possible given the people’s involvement. What is crucial is the building of that agency for change that was once fulfilled by the Tripartite Alliance now in the process of breaking apart. I am no clairvoyant and cannot predict whether the rot therein can be reversed; whether the efforts to establish a new united front, trade union federation and workers’ party some are contemplating will succeed; and the extent to which the emergent EFF, or SACP standing in elections as an independent workers party will become part of that agency. If the SACP can truly shed itself of the Zuma legacy and play its independent role it could prove a decisive force in the process. The challenge is whether the convergence of left forces will succeed and provide the basis for the essential driving force for change; capable of responding to events often entirely unpredictable as they unfold. What it is not difficult to suggest is that without that organised agency of change there can be no fundamental transformation. The working class is the decisive driving force in this regard.

We must keep alive the belief that change can happen and will come if we are properly organised; that people will become again aware of the reality of their situation and seek to confront the perverse and corrupt world for what it is. Such a movement will strive to reconnect with its own history in order to re-establish a different version of humanity, in which human potential might be realised, freed from the stunted form dominated by greed and selfishness that is regarded by many as natural.

Once mobilised and inspired the masses who are the true creators of history have the creativity and strength to storm the heavens. They will do so in a democratic participatory system, where the basic wealth and resources benefit the people as a whole. Call this People’s Power; give it the name of democratic socialism if you will. Another world is possible.

Publications

Publications

Partners

Partners