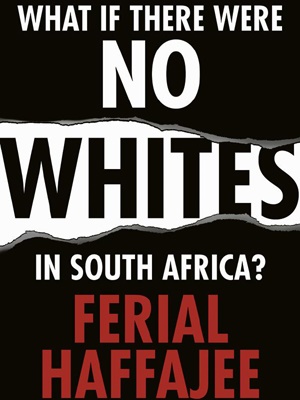

City Press editor in chief Ferial Haffajee’s debut book, What If There Were No Whites In South Africa? has attracted a number of heated responses. We asked two reviewers to weigh in

What If There Were No Whites In South Africa? by Ferial Haffajee

Pan Macmillan

256 pages

R233 at takealot.com

4/5

There is no debate in South Africa more urgent than how the role of race affects a whole generation of young people in terms of how they position themselves and their futures.

Race lies at the centre of our recorded histories, and the ways in which we struggle to negotiate the disadvantages of not being white.

The unrelenting juggernaut of whiteness is negotiated in the everyday experiences of a private school-educated, black student from North West at Wits University, just as it is negotiated by an Indian journalist like me from a relatively middle class background who still struggles with the voice of the white man as the final arbiter of what is good, right and just in the universe.

However, there is a disjuncture between a slightly older generation that recognises the structural faults in our society, but disagrees with the ways in which young people, like students at Wits, articulate their struggles against the stubborn remnants of racial hegemony. Ferial Haffajee is one such person.

In her book What If There Were No Whites In South Africa?, she claims that black aspirations are being hampered by the idea of white supremacy. She agrees that transformation is incomplete, but contends that the levers are firmly in black hands and white supremacy doesn’t have leverage over that transformation.

Moreover, she argues that the numbers in the black and white middle class have reached parity, nullifying what she feels is an unwarranted fixation with white privilege.

But the way in which this middle class has been constructed also bears scrutiny because it reveals exactly how shaky its prosperity is.

The growth of the new black middle class is attributed as much to government widening the civil service as it is to new lines of credit. As Dr Deborah James from the London School of Economics recently said in her research, it is indebtedness that imperils entire families as this new middle class increasingly struggles to make its repayments.

As many of Haffajee’s respondents point out in the book, “black tax” should force us to rethink how we define this new middle class because they have become distributors of their wealth rather than consumers.

However, Haffajee’s argument, or process of understanding as it ultimately becomes, feels hurried along without offering a sceptic much opportunity to be persuaded by her.

For example, I’m fascinated by her claim that young South Africans have been influenced by the situations of African-Americans, in effect confusing themselves about their own realities. Beyond an often-discomfiting veneration of Beyoncé as the epitome of human endeavour, I don’t see a direct influence. Still, I would have liked to read more about how Haffajee has made this assessment.

There is great value, I think, in intergenerational dialogue in South Africa. And this book is an attempt at just that kind of conversation. But What If There Were No Whites does fall short of what it could be. Haffajee’s discussion groups with people she feels are shaping the popular discourse on race significantly weaken the book. It does, in parts, feel like a conversation between Haffajee and the Twitterati.

I feel these discussion groups should have been the beginning of a greater enquiry into the thoughts, feelings and experiences of young people who aren’t writing books.

And this is not so much the fault of the author of the book, but the greater failing of the publication of nonfiction in South Africa.

Rushing books into production for the Christmas period without giving writers more room to reflect and research, and more time to contribute writing that provides meaningful engagement with what has happened and what is to come, is a disservice to the insight, knowledge and acumen of the writer.

Make no mistake, this is an important book that should be read and discussed. But ultimately, I feel we cannot answer the question its title asks without paying attention to South Africa’s position in a greater global scheme where political, social and cultural power is still firmly entrenched in the West. And this may go some way towards explaining why a generation of young people who have all the appearances of living their best lives are fixated with white privilege. It’s not about the presence of white people, but a culture that permeates the university, the workplace and many other places. Whiteness exists even without white people.

. Patel is an executive editor of The Daily Vox and a research associate at the Wits Institute for Social and Economic Research

Publications

Publications

Partners

Partners