As a schoolboy, Mteto Nyati knew that he wanted to fix and build things. In this extract from his new book, he speaks about his journey into engineering

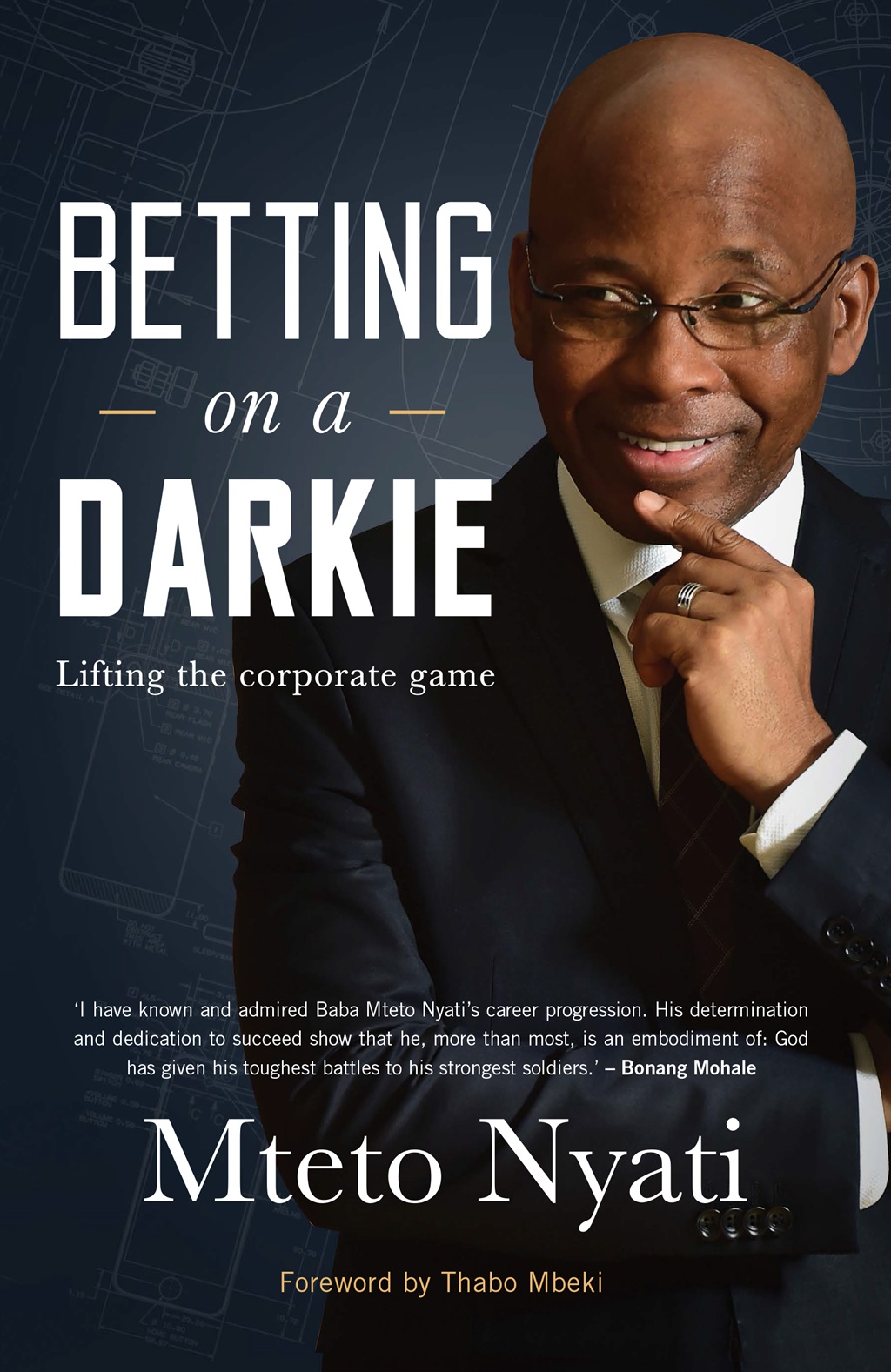

Betting on a Darkie by Mteto Nyati

Published by Kwela

272 pages

R245 at takealot.com

“Our character is not so much the product of race and heredity as of those circumstances by which nature forms our habits, by which we are nurtured and live.” – Cicero

My father wanted me to be a doctor: of that he made no secret.

He planted the idea in my head, and anyone else’s who would listen, when I was very young.

He’d wanted to study medicine, but in his day medical training for blacks was inferior and he felt sure he’d end up as a glorified nurse, so he studied to be a teacher instead.

Even long after I’d decided I wanted to study engineering, Bhuti, as I called him because I’d grown up hearing my aunts calling him that, didn’t stop trying to change my mind.

When, in 1982, he drove me to Durban from Mthatha to start my first year in the engineering faculty at Natal University (now the University of KwaZulu-Natal), he pestered me all the way.

“Bhele, why don’t you just do medicine?” was the intermittent refrain for more than 400km.

What made him more adamant was that residences were racially segregated and the only one that would accept black students was the Alan Taylor Residence in Wentworth, which housed medical students.

In addition, the government of the then “independent” Transkei gave bursaries to students who chose medicine.

Instead, he and my mother had to pay for my engineering studies, and I had to find digs off campus. It just didn’t make sense to him.

“Everything, Bhele, is pointing to medicine!”

In his mind, engineering was a bit like being a car mechanic – good for a hobby, but not for a career.

However, my mother had watched me, as a curious child, dismantling her radio to see how it worked, fiddling with car engines and puzzling over why a paraffin fridge was cold if it had a flame.

And she supported me.

“You do what you want, Dlambulo.”

When we got to Durban, my father drove straight to the medical school at King Edward VIII Hospital, hoping against hope that I would change my mind when I saw the place.

There, he met up with an old friend, a nursing sister, who agreed to provide me with accommodation in Umlazi.

We dropped off my belongings at her home, but I didn’t feel entirely comfortable with the arrangement.

While registering, I bumped into a school friend, Loyiso “Blackie” Magqaza, who told me about prefab accommodation for black Howard College students living at Alan Taylor Residence (used by black medical students).

I jumped at the chance of being spared the long commute to and from Umlazi.

I shared a dormitory with the likes of Thembani Bukula, Mce Booi and Manderese Panyana.

Many years later, when Thembani was the energy regulator at the National Energy Regulator of SA, he and his team had to withstand unrelenting political pressure, either not to put up Eskom tariffs because it was election year, or to put them up to afford the nuclear deal.

I felt proud of my former dorm-mate, who always did what he believed was right.

Thankfully, for my father’s sake, my brother Fundile, three years my junior, became a doctor.

My sister Pelokazi studied physiotherapy and the last-born, Langa, became an engineer like me.

Read: Book Extract: Expansive . Educated. An ex-con. It's hard to get into my mother's secret life

Both my parents were teachers, trained under the Cape education department before Bantu education was introduced.

They came from a long line of teachers – even my great-grandfather was in the profession. Bhuti taught Latin, English and history.

He was a great raconteur and loved connecting history and religion to real life, be it sitting around with his friends drinking whiskey, on the pulpit as a sub-deacon, as headmaster in front of his school or as master of ceremonies at a community function.

He particularly loved telling stories when he had a captive audience stuck in the car with him on a trip somewhere.

One of his favourites was recounting how our ancestors had fled from the warriors of Sigidi kaSenzangakhona – King Shaka – in the Mfecane wars of the 19th century.

When they reached the Eastern Cape, the Xhosas didn’t accept them either.

Various tribes, dispersed by the Zulu armies and shunned by the Xhosa, came together, forming the Fingo nation, a name referring to their status as wanderers, or displaced people.

After years of oppression by the amaGcaleka in the Transkei, the Fingo established themselves in the south-western corner of what is now the Eastern Cape.

In the 1830s, they forged an alliance with English missionaries – considered one of the worst things black people could do at the time, as it meant declaring loyalty to the British and their god.

But it was also a commitment to education.

And that shaped us.

Publications

Publications

Partners

Partners