As the sun begins to set on the life of internationally celebrated South African photographer Santu Mofokeng, his legacy and intellectual property have become the subject of a nasty fallout between the agent who helped restore his archive and establish his foundation and his wife who is the court-appointed administrator of his property.

City Press visited a frail Santu (63) at home in Kensington, Johannesburg, last week where he is bed-ridden and cared for by his wife Boitumelo.

He is unable to speak or send text messages.

In 2015 Santu was diagnosed with progressive supranuclear palsy, an uncommon brain disorder.

He had two children with Boitumelo, a community developer and ultramarathon runner. They divorced after seven years of marriage and remarried after he was diagnosed.

Now Boitumelo is insisting that a trust be established to house Santu’s archive and intellectual property – instead of the Santu Mofokeng Foundation, which was established by Santu’s agent, Lunetta Bartz, with, says Bartz, Santu’s blessing and on his instruction.

The foundation’s directors are Santu, Bartz and Santu’s long-time friend, German art critic and academic Sabine Vogel.

Vogel and Bartz insisted last week that Santu was clear about how he wished his legacy to be managed.

From 2009 Bartz began working with Santu to piece together his archive and publish a series of books on his work.

Bartz has an exclusive agency contract with Santu that is also the subject of legal challenges about to be launched by Boitumelo’s lawyers.

They accuse Bartz of exploiting Santu’s intellectual property and not exercising a duty of care in the agency contract, which gives her sweeping powers and assigns Santu’s rights to her.

Bartz is perplexed by the challenge, saying the contract was drawn up by Santu, not her. Santu’s then lawyer, Alan Jacobs, confirmed this, saying: “I drew up the contract and Santu’s will on his instruction. He was already sick but was compos mentis [of sound mind].”

But Boitumelo says Bartz assumed total control of all Santu’s business and all his money, even naming herself as the beneficiary of his funeral policy. Bartz wholly denies any of her claims, saying: “The death policy was again Santu’s suggestion, as he had almost no relationship with his immediate family.

“Once Boitumelo remarried Santu, I immediately requested we visit the bank and sign over all authorities and beneficiaries into her name. This was my suggestion and done without hesitation,” she said.

But Boitumelo showed City Press a document in which Santu writes that Boitumelo must be made his proxy with regard to the contracts he signed.

“He later also instructed Lunetta to make me ‘part of the machinery’,” she says. “This could all have been avoided if she had followed his instructions and if there had been transparency. It took Lunetta months to hand over the agreements with Santu and at one stage while I read them to him, Santu said to me that he is authenticating something that he never authorised.”

Bartz insists she went by the book, but Boitumelo’s lawyers want a full audit of all Santu’s financial affairs. Bartz says her books are open.

Things between Boitumelo and the foundation came to a head after last Friday’s launch of 21 high-quality photography magazines called Santu Mofokeng: Stories in Kliptown, Soweto.

Produced by German publisher Steidl, they are the result of years of work between Santu, Bartz and photography academic Joshua Chuang.

The team, with some family members, drove to Santu’s home to deliver a set of the books on the day after the Kliptown launch, but Boitumelo angrily turned them away.

She told City Press no arrangement was made for the visit.

“Santu is not a monkey in a zoo to be peeped at when visitors feel like it. They disrespected him and his family,” she said.

But the visitors deny trying to see Santu, saying they just wanted to drop off the books.

“It is truly unfortunate that our well-intended gesture is being interpreted in this way and that Santu has not yet had a chance to see the fruits of our labour,” said Chuang, who insisted that Bartz’s work with Santu had been selfless and invaluable in restoring his archive.

Boitumelo’s lawyers, though, have called into question the contracts signed between Santu and the foundation around publishing books, donating his archive and exhibiting his work.

They say Santu already assigned his rights to Bartz so couldn’t sign such deals as the rights were no longer his.

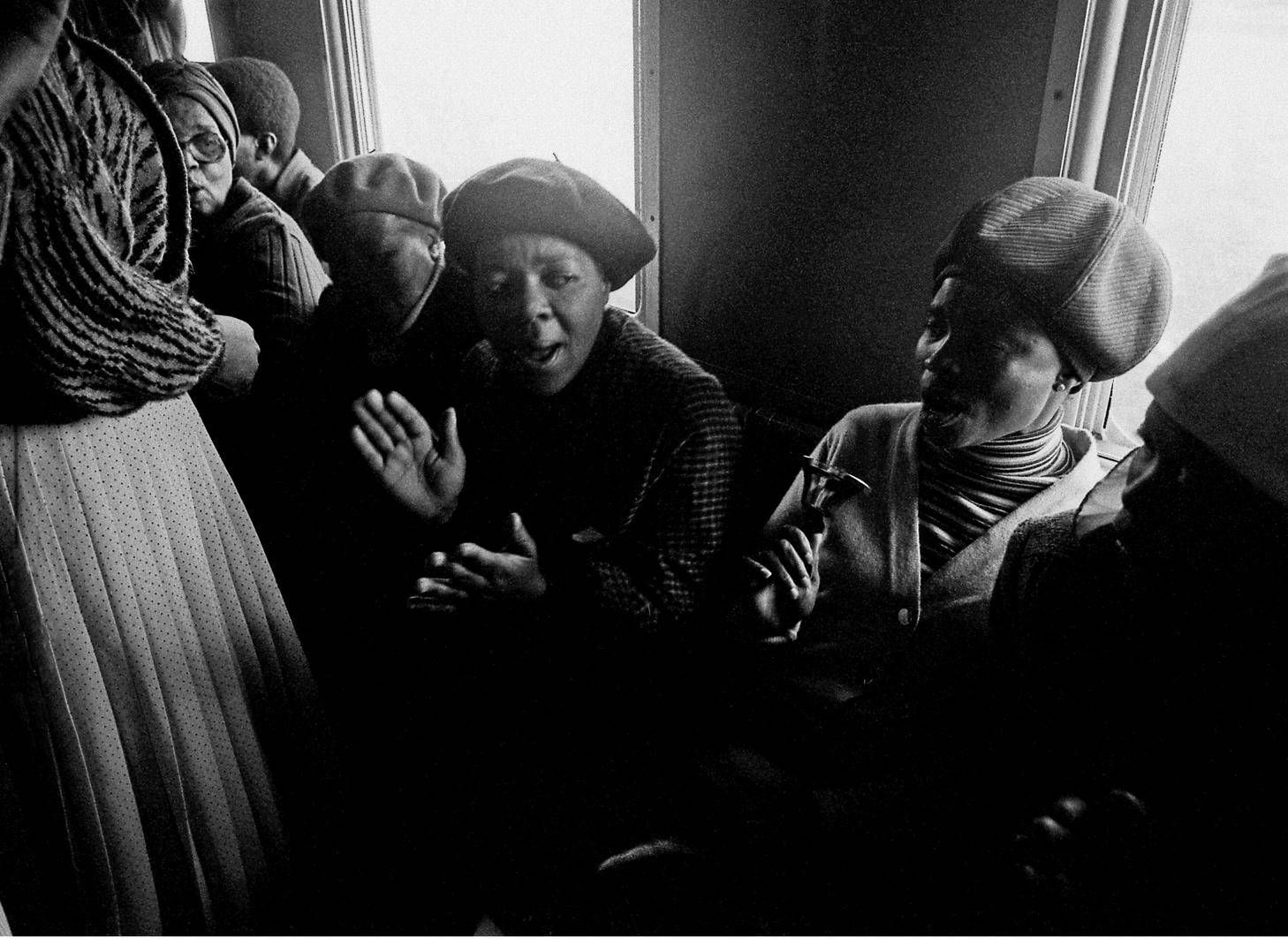

Santu, who has won numerous international awards, fellowships and scholarships, established himself as a street photographer in Soweto.

In 1985 he began working in newspaper darkrooms, launching a career documenting life under apartheid.

He was a member of the famous anti-apartheid photography collective, Afrapix.

Aside from his own work he would research and display archives of images of urban working class black families and became increasingly known for writing about his work.

He would achieve a second wave of fame as he began to document the spiritual life of the nation, including sangomas gathering in caves and churches on trains.

Bartz says she and many of her colleagues are saddened by Boitumelo’s refusal to allow them to visit Santu to say goodbye.

Santu’s sister, Meisie Mofokeng, accused Boitumelo of “refusing to let me see my brother. She’s thrown me out. My heart is very sore about it.”

Bartz showed City Press the last inscription Santu wrote to her in one of the books she worked on.

Dated March 5 2016, Santu writes: “I wouldn’t know how to leave without you being at the helm.”

“Right now my focus is Santu’s dignity and to care for him,” said Boitumelo last week.

“But it is equally sad for us that the agent has never been as forthcoming as she is being right now, yet when we needed her to inform us, she did not see it worthy of doing so. She treated us with disrespect. Clearly to her and her fellow director, Santu no longer has a say in a foundation in his name.”

|

| ||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||

Publications

Publications

Partners

Partners