Today is the day you have to go to class with the boy who sexually assaulted you. You will sit behind him to keep him in your field of vision. You will recall the way he said, “Let me pull down your panties so you can be a nasty girl, ’cos I know you like those things,” as he stood between you and the bathroom door.

Today is the day – even after he was found to have broken the student code and was expelled – that you will have to see the face that was pressed up against yours as he pinned you to the bathroom sink. Because today is just another day on campus, and you are just another woman who has been failed by a university’s disciplinary system.

. . .

Nineteen-year-old Larissa Mwanyama is a first-year fine art student at the Hiddingh Campus at the University of Cape Town (UCT), which houses the fine arts and drama faculties in the Cape Town CBD. On the afternoon of October 4 2015 at around 1pm, she says, she went to the women’s bathroom and was followed by a male student.

“I asked him: ‘What are you doing inside the bathroom?’ and he kind of ignored my question.”

The male student was Sipho Mpongo, a 22-year-old photographer whose work has been celebrated in these pages, a Magnum grant recipient, author of a frankly incredible photo series called Born Free, and one of the Michaelis School of Fine Art’s rising stars.

In his version of events, he “asked her if I should go inside the cubicle with her because I was confused as to what was going on ... I tried to kiss her and she said no and I let her go. We both left the toilet.”

UCT’s discrimination and harassment office, which processes complaints, and the university’s student disciplinary tribunal, which metes out justice, seal their hearings and records. The only reason this story can be told is because both Mpongo and Mwanyama have consented to interviews and agreed to be named.

Any information that was shared by UCT in the course of my investigation was garnered because UCT communications manager Pat Lucas was either confirming or denying the events I put to her.

Make no mistake, this is not an isolated case. According to UCT, “in 2015, the discrimination and harassment office received eight complaints dealing with rape, attempted rape and sexual assault, and 13 complaints of sexual harassment”.

How many cases went unreported is anyone’s guess.

. . .

On the morning of October 5, Mwanyama approached a senior student and mentor and told her about the ordeal.

After consulting staff, they were referred to the Student Wellness Service, which suggested that she speak to a dedicated campus counsellor. The counsellor would not be at Hiddingh for nearly a week, so the senior student drove Mwanyama to the Upper Campus. After they made the formal statement to the discrimination and harassment office, a no-contact order was obtained to prohibit contact between the accuser and the accused on university property.

Mpongo did not show up for the initial tribunal and a representative from the discrimination and harassment office indicated that they would get the order to him.

Mwanyama started to speak to other female students. Not only had she allegedly had a previous, similar incident with Mpongo, she was hearing that others had also been bothered by him and his friends. She says a total of 23 young women told her Mpongo had sexually harassed them.

The following day, in contravention of the protection order, Mpongo tried to speak to Mwanyama on campus.

A Michaelis student says: “This was a moment in which staff were required to take action with respect to the discrimination and harassment office’s procedure. They did not do so.”

It has now emerged that the order was served on Mpongo only three days after it was requested.

It was at this point that another member of Michaelis’ staff suggested to Mwanyama that she would be better positioned to study from her room in res so that she would not have to deal with the trauma of seeing Mpongo on campus. Additional teaching materials would be sent to her.

Essentially, this would have cut her off from all of her support networks on campus. The hearing was postponed and Mpongo continued to attend classes.

How did it get to the point where a first-year student at the country’s most prestigious art school could allegedly commit dozens of acts of sexual harassment before he was called out? The fact that almost none of the 13 students and lecturers I spoke to wished to be named for fear of negatively impacting their careers speaks volumes.

. . .

To zoom out for a moment, an incident that occurred at the drama department’s mock awards event in November is illustrative. One tongue-in-cheek category included “best on-stage kiss”. The winners went up to receive their crowns and the crowd chanted: “Kiss! Kiss! Kiss!” The young woman politely refused. The young man grabbed her by the head and forced his face into hers. The crowd burst into cheers, even after it was plain that the girl was upset and traumatised. She quietly left the function.

There was a rape reported during the #FeesMustFall protests, in the epicentre of safety – Azania House. To catch the alleged perpetrator, female students named and showed a photo of him on social media, having given up on achieving justice through the system in a country awash with sexual violence.

I don’t wish to diminish Mpongo’s actions, but in my opinion they cannot be considered in isolation. It could be argued that 400 years of colonialism and the apartheid migrant labour system damaged black families and caused untold generational damage by taking away fathers. At its core, any system of patriarchy is bound to result in violence.

And we need to remember that a university such as UCT, with its abundance of white art graduates, needs bright talent like Mpongo, and seems willing to go so far as to forgive him practically anything just to be able to say it has this young black star to prove that it is not a racist institution.

. . .

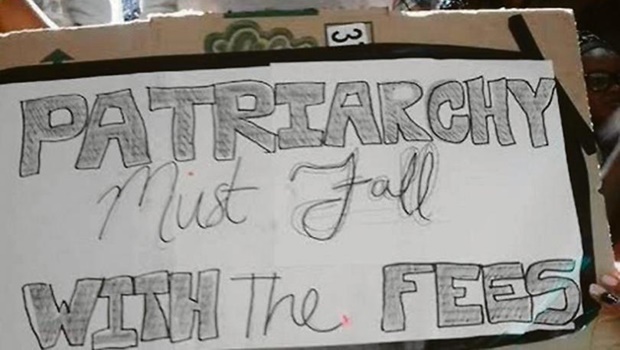

On October 15, on the eve of the #FeesMustFall uprising, a protest action was held at Hiddingh, organised by Mwanyama and other students, following what they felt was a distinct lack of decisive action. The march was made up of 20 to 30 almost exclusively female protesters. One of them, in frustration, broke her silence and named the accused as Mpongo. This was captured on video, along with a claim that the protesters knew of 59 incidents of sexual harassment by Mpongo and other young men.

The march moved to the Michaelis building, where a lecture was taking place on masculinity and violence. Associate professor Fritha Langerman met the march.

When I spoke to Langerman the week after the protest, she clarified that the discrimination and harassment office was the only process available and had to be allowed to run its course, but she did add that the problem of sexual harassment of students on campus was “vast and unspoken. More students need to come forward.”

Langerman’s statement was echoed by Lucas: “We are concerned that many students try to deal with the trauma of such an offence on their own ... This is especially tragic when such effective forms of support are available at UCT – a logic that seems to suggest that victims of sexual violence are to blame for non-reporting.”

After the eventual hearing, when asked about how he felt about the march, Mpongo said: “[It] made me feel their pain, and it never occurred to me that such behaviour was wrong towards women. I came to a realisation about how I grew up back home speaking about women ... It is such a sensitive issue and I was in total solidarity with them. There is a fine line between wanting to date someone and probably mistreating them … We are not taught much about treating women in South Africa.”

. . .

In an as yet unsent letter to Michaelis staff, another student states that the accused “took advantage of the platform of his final foundation course lecture to deliver a speech about his role in the alleged assault. He stated that he and Larissa were only ‘playing’.”

Mwanyama responds with quiet determination: “This is not true and he knows this, and for me to have to clarify this constantly is insulting, disgusting, unnecessary.”

The letter goes on to say that nothing was done to stop Mpongo’s speech, “regardless of its potential to trigger other students who have come forward and claimed harassment by this same man”.

During this, the assaulted student sat in her res room, afraid to attend class.

In his interview, Mpongo is apprehensive at first. When asked about allegations of other incidents, he said: “I intend to do intense research about my behaviour and [that of] my friends around me. I am doing introspection and I am seeing a psychologist. All sorts of help is needed.”

. . .

At the Hiddingh Campus, students often work late, often alone. “When somewhere you consider a home-like place is violated,” says a student, “it makes you re-evaluate just how safe you are there ... On a few occasions, I have gone through escape strategies in my head.”

The fundamental problem lies with the system.

Says one of the protest organisers: “People kept saying we would ruin his career. I say he ruined his career the minute he laid claim over someone else’s body. That type of arrogance comes from knowing he can get away with it. It’s a shame that someone’s career and image are more important than another’s life and wellbeing.”

There is an anecdotal story that has been told to me by three different women about a male artist in the master’s group who no longer speaks to women at Michaelis.

“I guess this is intended as punishment for what is clearly ‘a conspiracy’ targeting Sipho, undoubtedly run by some secret feminist cartel,” says one.

I was even contacted by two different prominent male artists, asking why I was “persecuting” Mpongo.

. . .

The closed-door hearing was set for November 14, at which the accused would represent himself, and Mwanyama would find herself in a room with only her lawyer, a mediator and her alleged attacker. Eventually, the hearing happened on November 24.

“Because Sipho chose to defend himself ... he had to sit through the whole procedure, while I only went in for my statement,” says Mwanyama. “I didn’t hear the ruling, I didn’t hear his statement ... He went in first because they had to press charges ... And then Sipho had to ask me questions. So he asks me, ‘Larissa, if you saw me following you to the bathroom, why didn’t you tell me to go away?’ I said I knew exactly what he was doing ... because the boys’ bathroom is at the bottom of the staircase ... and the girls’ bathroom is at the top.

“Then he went off: ‘Larissa, I don’t know where this is coming from; we were friends! I don’t know why she’s doing this ’cos she called me to the bathroom, and I was her friend – so I went with her and she nagged me to be with her, so I stayed.’”

She continues: “What really upset me was that the assessors almost took his question into serious consideration, because, thereafter, the questions were, ‘Oh, but Larissa, why didn’t you tell him to go away?’ All I could think of was why am I held under trial? The whole situation was very uncomfortable. I didn’t feel like anyone really took what I was saying seriously. It was almost like he’s been given, like, a get out of jail free card.”

. . .

The next day I sent further questions through to Lucas, who responded almost immediately: “The student disciplinary tribunal has finalised this case. The student was found to have breached the student code; was expelled; the expulsion was suspended; and a sanction of 65 hours of community service was imposed.”

My interview with Mpongo took place by email a few days after the hearing. After two weeks of not hearing from her, I sent Mwanyama follow-up questions. Both she and Mpongo confirmed that they would be attending Michaelis in 2016.

Although she would eventually receive an email from UCT about the outcome of the hearing, Mwanyama first heard it from me. In the case of Mwanyama vs Mpongo, UCT neglected to timeously inform the complainant of the outcome.

“I am just satisfied that there is an outcome. I genuinely thought that the board would come up with another delay,” she told me. “However, I am concerned about whether Sipho understands how intense his offence was ... I am uncomfortable that we will be sharing the same space next year, but I have to deal with it and move on. Most of the time, I felt very alone and out of the loop. Sometimes it felt like all the responsibility was on me.”

If UCT’s system had been more effective, if it did not reinforce in young men’s minds that they were entitled to women’s bodies through the system’s very muteness, then Mwanyama and Mpongo would not be in that classroom as adversaries in 2016.

In the end, Mpongo still claims Mwanyama led him by the hand to the bathroom, but he “was wrong for thinking what Larissa and I had was consensual. It is hard to be a man in this country. What the law says and how people behave, and the notion of love and being loved, is also different.”

Mpongo concludes his final WhatsApp conversation with me by saying: “I have a greater responsibility of finding out what it means to be a man in this country.”

Mwanyama, however, is under no illusions about what it means to be a woman.

. It is simply not the case that UCT “needs bright talent like Mpongo, and seems willing to go so far as to forgive him practically anything just to be able to say it has this young black star to prove that it is not a racist institution”. Mr Mpongo was charged and found guilty on four serious charges and a sanction was imposed; he was not, and has not been, forgiven.

. Mr Mpongo was charged under the UCT student code and found guilty of sexual harassment, sexual assault and interfering with the complainant in this case in such a way as to create an intimidating, hostile or demeaning environment.

. The university’s Student Discipline Tribunal expelled Mr Mpongo, but suspended the expulsion on two conditions: that he completes 65 hours of community service and that he does not commit any further offence while a student at UCT.

. A no-contact order was served on October 9 2015, three days after the complainant applied for it, and a disciplinary case followed.

. UCT takes the question of gender violence seriously – but that is not to say that we have succeeded in eliminating the problem on campus.

. The discrimination and harassment office has a specific mandate to help students and staff members to better understand and change attitudes towards gender discrimination, sexual harassment, other forms of harassment, domestic violence and rape; it provides a counselling and mediation service and supports victims through disciplinary processes. We also have a 24-hour whistle-blower hotline.

* An earlier version of this story was missing a paragraph due to a technical error. It has been inserted.

Publications

Publications

Partners

Partners