What changes can we expect for our country and our lives as climate change takes hold? Mandi Smallhorne asks the experts

The good, the bad and the ugly; it’s already becoming apparent that the effect of climate change is a mixed bag.

Some of it can look quite pleasant (milder winters and fewer chilblains on the Highveld, for instance); most of it falls within a range from “oh dear” to very scary.

The broadest take on climate change’s effect on us is that, “in the next 30 years, the western parts of South Africa are expected to be hotter and drier than the rest of the country. More extreme weather, droughts and floods can be expected,” according to the State of Climate Change Science and Technology in SA report, which was compiled by the Academy of Science of SA on behalf of the department of science and technology.

Over a 50-year time frame, there will be significant changes in what activities – especially agricultural – are viable and where, said one of the country’s most distinguished climate scientists, Robert Scholes, professor of systems ecology at Wits University.

We have a lot of them: South African research institutions and universities boast world-class scientists doing world-class research in this field.

“The key issue is temperature, rather than rainfall, especially in the arid interior,” he said.

South Africa started down the path of climate change as a semiarid country that already had a fairly tight margin on water and regular droughts.

Even if we’re really lucky and rainfall continues at the same low but liveable levels, with significantly higher temperatures, we’ll benefit from less of the rainfall as evaporation will suck water off dam surfaces and out of the soil faster.

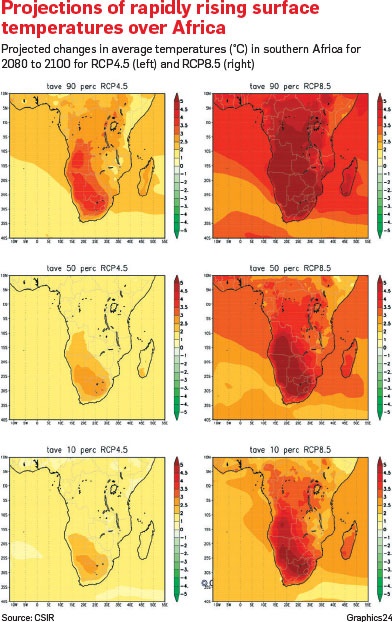

For rather scary detail on what those high temperatures could eventually be, turn to a recent presentation by Johan Malherbe and Francois Engelbrecht, scientists at the Council for Scientific and Industrial Research: “The Free State and North West are projected to drift into a temperature climate regime not observed in recorded history. Temperature increases of 5°C to 9°C are plausible by the 2081 to 2100 period. Significant rainfall reductions are projected.”

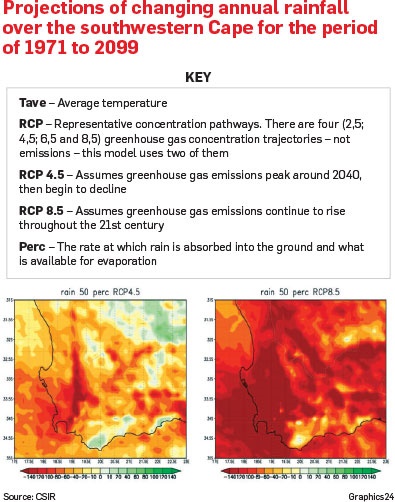

The southwestern Cape is also drifting into a climate regime not observed before, albeit with lower projected increases in temperature.

In January, Bloemfontein recorded temperatures in the high 30s, so a 5°C to 9°C increase would push the city into record highs and make it seriously uncomfortable territory.

Whether it ends up being closer to 5°C or 9°C depends on how fiercely we as a species fight to mitigate climate change.

HEAT WAVES AND FIRE RISKS

But weren’t we aiming to keep the global average temperature increase below 2°C? Where do these wild, frightening figures come from?

Unfortunately for us, not only have we not yet come close to doing enough to keep the increase below that magic figure, there are also special climatic features that put much of Africa at risk of increases at least 1.5 times that of the rest of the world in the subtropics.

In 2015, atmospheric modeller Engelbrecht and colleagues predicted “plausible increases of 4°C to 6°C over the subtropics and 3°C to 5°C over the tropics by the end of the century relative to present-day climate under the A2 [a low mitigation] scenario of the Special Report on Emission Scenarios. High-impact climate events, such as heatwave days and high fire danger days are consistently projected to increase drastically in their frequency of occurrence. General decreases in soil moisture availability are projected, even for regions where increases in rainfall are plausible, due to enhanced levels of evaporation.”

The scientists warn that “these projected increases, although drastic, may be conservative given the model underestimations of observed temperature trends”.

But these predictions are a long way off. Why should it matter to you how hot it’s going to be in 2080?

Because it’s happening already. We’re already well on the road to the “hot mess”.

In 2014, University of Cape Town climate scientists Neil MacKellar, Mark New and Chris Jack crunched the data for the 50 years from 1960 to 2010, and they found that “maximum temperatures have increased significantly throughout the country for all seasons, and increases in minimum temperatures are shown for most of the country”.

They said that “a notable exception is the central interior, where minimum temperatures have decreased significantly”, which means that, in the interior, daytime temperatures were going higher, while night-time temperatures were going lower.

This has important implications for all sorts of things, from plants and animals to infrastructure – think cement or tarmac that’s stressed by contracting under cold and expanding under heat.

HEAT STROKE AND ECOSYSTEM LOSS

And us, of course. All mammals – and humans are no exception – maintain a tight temperature range.

In our case, it’s about 37°C.

As any parent who has anxiously watched a sick child’s fever knows, just a small shift outside that range spells trouble.

When the ambient temperature (the temperature of the environment around you) goes above 38°C, you’re at risk of heat exhaustion. At 40.6°C and more, heat stroke becomes a risk.

This can be deadly – more than 40 Japanese people have died in persistent temperatures of 38°C since the beginning of July.

In fact, things get serious long before that, as quite mild increases in heat carry off the vulnerable – the very young, the ill and the elderly. In a European study, the death rate started to rise above normal at 32.7°C in Athens.

Livestock suffer similarly in the heat and, as professor Scholes noted, in many areas we’re already “quite close to the level where livestock is not really viable”, so we don’t have much margin to play with.

We can move some livestock to warmer areas that were previously too cold for them, but it’s a slim budget of land.

Wildlife face the same predicament, except they can’t move as easily, as they need to take a whole biome with them – food plants, insects, birds and all.

This is one reason the Kruger National Park faces the prospect of losing two-thirds of its species, a dramatic loss that will affect tourism and the ecosystem.

Recent major flooding in the park was “due to an increasing frequency of cyclone-driven extreme floods”.

This has also been very damaging to the rivers in the park, and to the species that depend on their ecosystem services, according to UK researchers, who reported their work earlier this year.

But there are some species that are prospering and will continue to do so with climate change.

Microbes like cholera, for example, will be able to spread rapidly in polluted waters and in floods; rats (and other pest species), the populations of which are already exploding in urban South Africa, love the warmth and the rapid growth of our cities.

Already, two-thirds of South Africans live in cities and predictions are that, by 2050, three out of four of us will be urbanites.

And cockroaches. Cockroaches grow more active with rising temperatures – if that’s not a good reason to fight climate change with all your might, I don’t know what is.

Well, maybe there is the effect on your lungs, on respiratory health: “Climate change may have a direct effect on air pollution in South Africa,” Dr Caradee Wright and her colleagues wrote in the SA Medical Journal in 2014.

“It is likely that surface-level ozone and particulate matter, two factors that contribute greatly to air pollution, could be most affected by climate change.”

And, as the warmer growing season expands, pushing winter back so that spring comes sooner and sooner, so the pollen season, with all its discomforts for allergy sufferers, gets longer.

Challenges to food security, to human health, to Africa’s iconic animal species (and thus to tourism and the game industry), to growing cities and shrinking agricultural zones … We’re firmly on the road to this future, and some of the scary stuff is inevitable, scientists say.

Citizens and government alike need to pay attention to what science says about the years just ahead of us; we need to be fearless advocates for firm and decisive action on the international stage.

And, at home, South Africans need to be agile, innovative and creative to find ways to live in this new world.

It’s a clarion call to action – not just to fight climate change, but to adapt to it and live within it.

.This is the fifth feature in a series on climate and food security. It was made possible with the support of the African Academy of Sciences

Publications

Publications

Partners

Partners