Mishka Titus, who suffers from bipolar disorder, schizophrenia and epilepsy, visits the Manenberg Clinic to find peace.

It’s a strange refuge: the area it is set in is so violent that the clinic has bulletproof glass windows and panic buttons connected to the local Metro police in its rooms.

Over the past month, 17 suspected gangsters have been shot dead amid a vicious turf war.

On Thursday Titus, a 36-year-old mother of three, was there again – this time for a pregnancy test.

“Given my situation, I am hoping that I am not pregnant again. But God willing, you know?”

Titus and her security officer husband, Moenier, and their children, Marijuan (15), Mozamuel (9) and Maria (3), live in a Wendy house in her mother’s back yard in Renoster Walk, a kilometre away. They survive on disability and child support grants.

On the days when bullets and fists fly, Titus cannot get to the clinic. Renoster Walk is a point where clashes happen between the Hard Livings and Americans gangs, and its inhabitants are frequently forced to hide in their homes.

On Wednesday, just down the road in Jordan Street, a Hard Livings boss was shot and killed.

“When there are shootings, I am scared to walk to the clinic, because those bullets can hit anyone. I fear for my children and for my life,” says Titus.

“I go to the clinic often for my children, as they are asthmatic. I also go to speak to the sister about my problems. When I leave there, I always feel like a better person.”

Manenberg is home to about 61 000 people, most of whom live in council flats and semidetached homes. Families sleep huddled in their passages, away from glass windowpanes that shatter when bullets hit them.

But the Manenberg Clinic, with its neat face-brick façade and tall, barbed wire-topped fence, is an island of refuge.

Up to 200 patients flock there every weekday – including up to 80 children – seeking treatment and solace. The clinic offers basic health checks, antenatal services and, on Mondays, TB treatment.

When City Press arrived on Thursday, a security guard asked us to park in front because cars were more likely to be stolen at the back, despite the fencing.

Speaking at the clinic, Christine Jansen (53) – who grew up in Manenberg – recalls first going there when she was six years old. Manenberg has always been rough, but she thinks it’s getting worse.

“We are seeing an increase in the youth abusing substances and dropping out. It is often not safe at school, where kids smell of dagga or fall asleep,” she says. “From about nine years old, kids join starter gangs ... These laaities all go to jail or die at some point.”

With a sweep of the arm, Jansen points out various bits of gang turf sprawled out around the clinic: “That way you have the Hard Livings, there you have the Clever Kids, the Americans, and the Ghetto Kids near the train station.”

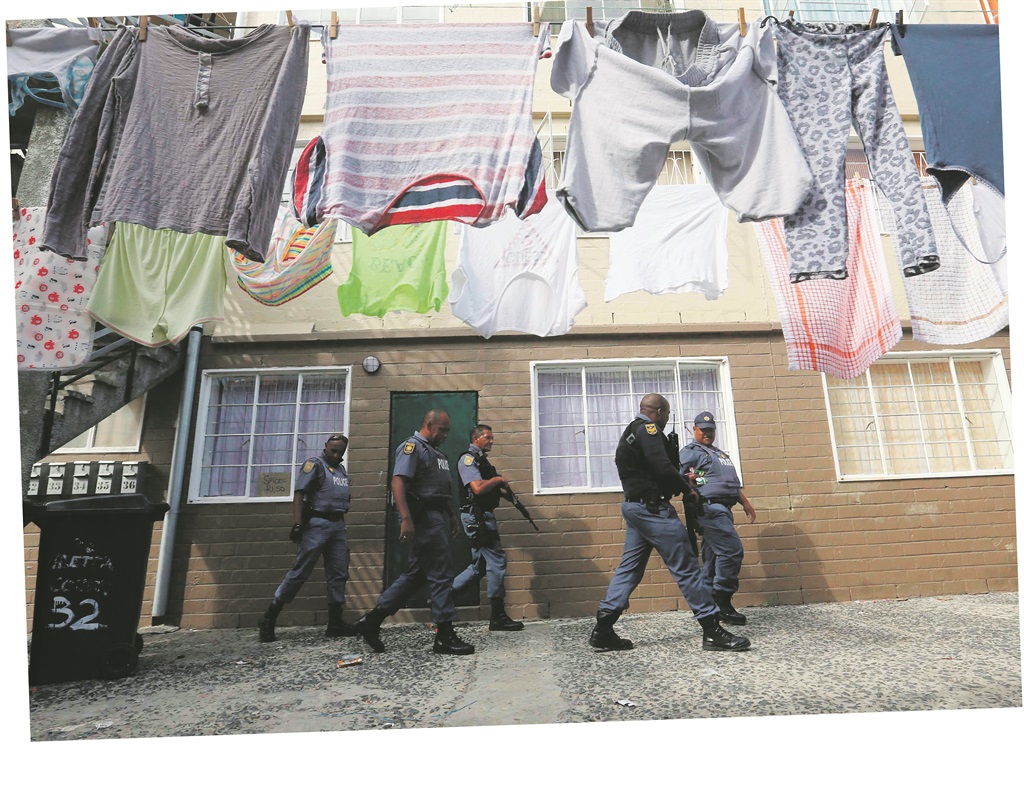

The gang crisis in Manenberg even spurred the parliamentary portfolio committee on police to visit the neighbourhood last Friday, after 17 people were killed in less than a month.

Police statistics show that Manenberg had the third-highest drug-crime figures of all the country’s police precincts last year, recording 3 191 drug-related crimes and 63 murders.

Inside the Manenberg Clinic, with its bright corridors and waiting room filled with pregnant women and toddlers on neat rows of chairs, the despair of crime and broken families feels somewhat removed.

The floors are gleaming blue linoleum and the walls are freshly painted, with informative antenatal posters and, along one corridor, a sign that reads: “No kimbies (nappies) here”.

The clinic’s manager, sister Judith Hendricks (52), was there, even though it was supposed to be her day off.

Hendricks’ office windowpanes are also bulletproof, and there is a panic button within reach of her desk. Her walls are lined with certificates for service excellence and, on a shelf, a large silver trophy stands next to a potted plant.

The Manenberg Clinic has won the trophy – awarded annually to the best of nine clinics in the Klipfontein subdistrict on the Cape Flats – three times.

“It is important for people to know that despite the situation outside, we are accomplishing so much in here,” she says.

She has been at the Manenberg Clinic for three years, after moving from the nearby Hanover Park Clinic, where she worked for 10 years. She says she loves her job and that she has grown accustomed to the violence surrounding her.

“In Hanover Park there were selective shootings – at 8am, and then maybe again at 12am,” she says.

“But here in Manenberg, wow, it just continues. Violence can erupt at any time; especially on days of funerals, they shoot.”

She adds that the clinic has strict protocols when violence flares up: “We close the gates and the building, and call the Metro police. They are usually here within minutes. Then we continue.”

Hendricks, who lives 6km away in Lansdowne, says that although she is not scared, some of the clinic’s suppliers are more wary. “We always let our couriers know when they must not enter Manenberg.

“I am not fearful, but shame, some of the IT guys, for example, are very scared,” she says with a smile.

Hendricks had always wanted to be a nurse and started training at the Somerset Hospital in Green Point when she was 21. Despite her years of experience, the horror that children face has never become easier to deal with.

“Especially not with children. I always see in them my own children, or my grandchildren,” she says.

But she is grateful that she can make a difference.

“I have the opportunity daily to improve people’s lives, and it is a daily blessing.

“I would not change my job for anything, or move away from the Manenberg Clinic.”

Publications

Publications

Partners

Partners