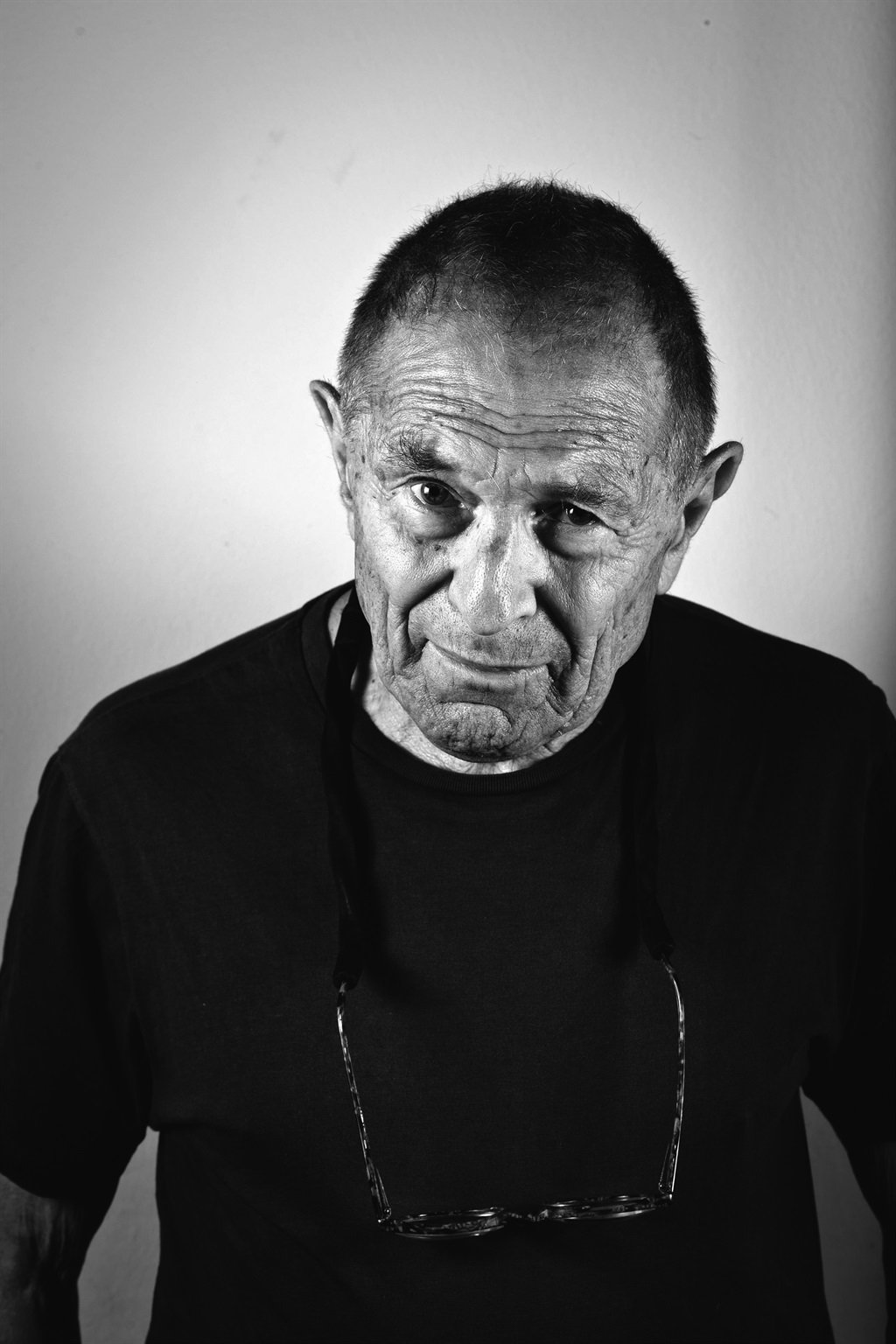

On Monday, a giant of South African photography, David Goldblatt, succumbed to cancer at the age of 87. His longtime friend, fellow photographer and the curator of a new showing of his archive, Paul Weinberg writes of the Goldblatt he knew

David Goldblatt was a mighty tree in the forest of society, a colossus among his South African and global peers in the world of photography.

It is hard to imagine the world without David Goldblatt. He was ever-present, bulletproof and seemingly immortal. An Übermensch, a mentor, father figure to many of us who knew him and a loyal, wonderful friend.

David the photographer was a colossus among his peers. He held a mirror to South African society. Whether on the mines, among Afrikaners, in Soweto, through our architectural structures, or reflections and refractions of our scarred, but beautiful, landscape.

He was deeply committed to this place, exploring and excavating its contradictions and imperfections. It is here he resonated, the photographer and the storyteller. No other environment attracted him.

At times he yearned for the freedom of just losing himself in the beauty of the land. He considered becoming an economist for a while in his early years, but there was a life he was drawn to explore. “What I knew in my gut was that I wanted to experience the stink, the feel, the piss of reality. As a photographer I knew I could experience something like that.”

. . .

South African reality drove and deeply troubled him at the same time. As he once said: “Something in reality takes me. It arouses, irritates, beguiles. I want to approach, explore, see it with all the intensity and clarity that I can. Not to purchase, colonise or appropriate, but to experience its isness and distil this in photographs.”

David’s isness was his metier. As someone privileged to journey with and through his archive, I have often stopped at an image for a while, pausing to take in the complexities, absorbing its technological artistry, its meaning and its depth.

These little pit stops have arrested, provoked and fascinated me. Whether it was an image in Hillbrow of a young white couple, a migrant worker deep in the South African mines, a young boy with broken arms in plaster taken at the Black Sash office during the turbulent 1980s, or a rare, on-the-fly, spontaneous moment.

In recent times I have returned to his archive again in preparation for an exhibition called On Common Ground, to be shown at the Goodman Gallery, where he and Peter Magubane will exhibit together for the first time.

There are so many Goldblatts that speak to the core of our society and that challenge our comfort zones.

But on reflection, David’s life work was essentially about the celebration of the ordinary, as Njabulo Ndebele once wrote, and how we danced our South African dance.

David once shared his approach to photography with me in a project called Then and Now.

“Photography to me is a tool to show the world. Whether I convey the mysteries in my photographs, I don’t know. I follow my ideas. I get to work, see what happens and then turn the pictures into series. The series may take several weeks, or several years. I followed one series for 15 years.”

Out of this emerged the books and exhibitions we have become so familiar with and that have become the embodiment of his oeuvre.

On the Mines, Some Afrikaners Photographed, The Structures of Things Then, Intersections and many other iterations and reiterations.

. . .

But the making of David Goldblatt the photographic icon took a lifetime.

In the early 1980s, as a young newcomer to Johannesburg, I bought a copy of On the Mines at a bookstore for R1.50, discarded and dumped on a pile of “for sale” books.

The same book today would, depending on its condition, be valued at between R3 000 and R5 000.

In a way, it’s a reflection of how David moved from relative obscurity to earn national and international acclaim.

It was only really late in his life, in the early 2000s, when photography became a feature in the fine art world, that the world caught up with David’s immense body of work and David caught up with the world.

He was the recipient of many prestigious international awards.

David always acknowledged he was a flawed photojournalist. After covering an ANC protest meeting during the 1950’s, commissioned by an international magazine where he was to meet Nelson Mandela, Walter Sisulu and others for the first time, he discovered, to his great horror, that his film hadn’t wound on.

It was a cataclysmic moment when he abandoned his idealism to become a “missionary with a camera” to instead pursue an approach that sought to engage with the underbelly of our society beyond events.

“It was to the quiet and commonplace, where nothing happened and yet all was contained and imminent, that I was drawn,” he reflected.

“During those years, my prime concern was with values – what did we value in South Africa, how did we get to those values and, in particular, how did we express those values? And once you start on that line of thinking, then it’s a continuation ... After apartheid I’m now concerned with how we are expressing our values now, what are our values? I’m as disgusted by some of the values we have now as I was with some of the values we had under apartheid.”

But to embrace a full 360 degree sense of David Goldblatt, is to know the man behind the lens.

. . .

Born in 1930 in Randfontein, a mining town to the west of Johannesburg, his parents Eli and Olga Goldblatt arrived from Lithuania to avoid persecution for being Jewish.

His father had a clothing store and his mother was a typist.

As a teenager already, Goldblatt started taking photos, but studied commerce at Wits University. It was only when his father died that he decided to sell the shop and pick up his cameras fulltime.

While an immensely private person, he had a generous community spirit. He ran workshops from his home for years.

He was the founder of the Market Photo Workshop, that became a catalyst for emerging African and South African photographers, and a co-founder of the Ernest Cole Award. While he often claimed he was not “political”, he exhibited widely throughout the turbulent 1980s in collective exhibitions that exposed the abhorrent apartheid society.

David was always there – a phonecall, an email or a visit away. So many beat a path to his door to seek his advice. From international curator to student, established and aspiring photographers. He turned no one away.

But while he was generous, he could be brutal in his criticism. He had an intellect that could cut the air with a knife.

I witnessed on many occasions, in meetings, how David was able to turn a large boat steaming ahead on course to its destination, 360 degrees in the opposite direction.

When David spoke we listened. And when you challenged him, you had to have all your Smarties together.

. . .

He was courageous and stood up for his views and values. He famously turned down the Order of Ikhamanga in Silver award from then president Jacob Zuma, at a time when the notorious “information bill” was being promulgated, because he felt it was a violation of our civil liberties and contemptuous of the spirit of our Constitution.

He withdrew his archive from the University of Cape Town because he felt the institution did not take a stand on censorship.

When its vice-chancellor Max Price accused him, Magubane, Omar Badsha and myself of contributing to “institutional racism” through our alleged portrayal of oppressed people, he took a stand.

David was a person in his own right, WRIT LARGE. He hated pomp and ceremony and being the centre of attention.

He was loyal to his contemporaries in religiously attending exhibitions and sharing their celebrations, but was quickly in and out, avoiding waxing lyrical over a glass of wine.

Asked to make a speech at photographer Paul Alberts’ funeral in Brandfort, the town most famous for the banishment of Winnie Mandela, David pitched up in “uniform”: short pants, boots and a flak jacket.

To celebrate his 80th birthday, usually a momentous occasion with lavish catering, he invited a small group of close friends to Steers for breakfast, a restaurant that became his favourite because of all his travelling in his camper van.

His order was always the same: two fried eggs, well done, brown bread, two crisp rashers of bacon, mushroom and grilled tomato washed down with black coffee. He knew who he was and he knew what he wanted.

. . .

At the funeral at West Park Cemetery this week, the rabbi, when speaking of David, said the spirits of people who have done evil die while they are alive, and the spirits of those who have done good remain alive after they have passed.

At the ceremony, a cold wind blew for a while and then receded. David was there – he will always be for those who knew him and whose lives he touched so profoundly in multiple ways. His photographs will continue to speak for eternity in their extraordinary humanity and poignancy.

. Weinberg is a photographer, teacher, film maker and curator. On Common Ground opens at the Goodman Gallery in Johannesburg on July 28.

Publications

Publications

Partners

Partners