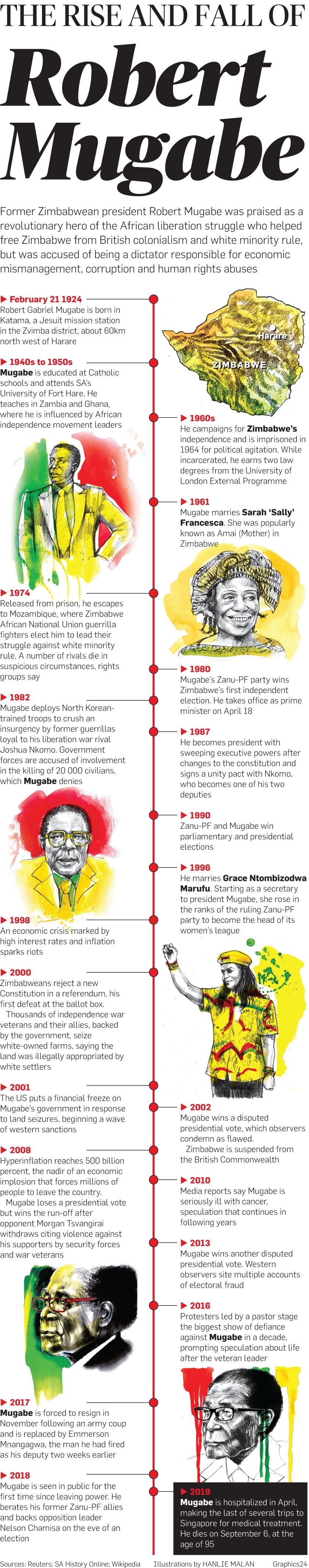

The one-time hero has left behind a country in ruins, its economy in tatters, its moral fabric torn by poverty and suffering

Robert Gabriel Mugabe’s name should have been there in the pantheon of Africa’s greats.

He should have been counted with the likes of Kwame Nkrumah, Kenneth Kaunda, Julius Nyerere, Jomo Kenyatta, Eduardo Mondlane and Agostinho Neto – men who led the unshackling of their countries from colonial rule to established free African republics.

In a perfect world Mugabe, who died on Friday aged 95, would have been universally hailed as a hero.

His mistakes would have been recognised but put down to normal human frailties.

Zimbabweans would have been pouring out on to the streets, wailing publicly for the fallen father of the nation.

They would have been crying “what will we be without you?”, as South Africans did when a long-retired Nelson Mandela died.

Across Africa and the diaspora there would have been heartbreak at the passing of a tough and brave giant.

This was not to be. The verdict on Mugabe was mostly that he was a vile villain who in his later years brought anguish to his people and left a country of great promise in a state of desolation.

There were sycophants, hypocrites and ostriches with heads in the sand who came out to praise Mugabe in the past few days but they were few and far between.

Those who praised him did so on the basis of his valorous role in the struggle for independence; the credible manner in which he ran the country in the first decade; the support he lent to liberation movements after Zimbabwe attained freedom and his willingness to stand up to Western powers.

On that they were right. One cannot take away his revolutionary credentials.

Mugabe was an unlikely revolutionary.

Coming from a devout Catholic family at a missionary outpost in Mashonaland, Mugabe was a timid and bookish boy who was always bullied by his peers at the mission school.

Even when he was a student he showed little interest in the activism that was stirring at tertiary institutions.

This lack of interest continued during his early teaching career.

It was only when he went to study at Fort Hare University – a hotbed of anticolonial and anti-apartheid agitation – that Mugabe was infected with politics.

There, in the company of students who would later become leading figures of the ANC and other African liberation movements, Mugabe found his anticolonial voice.

By the time Mugabe returned to his country, Marxism, Africanism and anticolonialism were flowing in his veins.

As a teacher in Southern Rhodesia (Zimbabwe) and Northern Rhodesia (Zambia) and newly independent Ghana he immersed himself in politics.

With Joshua Nkomo, later to become his arch-nemesis, they forged resistance organisations that would culminate in the formation of the Zimbabwe African People’s Union (Zapu).

In later years factional battles saw the banned Zapu split and Mugabe and others formed the Zimbabwe African National Union (Zanu).

It was his 11th imprisonment in 1963 that resulted in Mugabe earning legendary status. While not on the same scale, he became a Mandela-like symbol of resistance.

It was only natural then that when he was released and went into exile he would emerge as the foremost figure of the liberation struggle. Operating from Mozambique, he had by 1977 seized total control of both the party and its military wing the Zimbabwe National Liberation Army (Zanla).

In the annals of guerrilla warfare the exploits of Zanla and the rival Zapu’s Zimbabwe People’s Revolutionary Army are writ large.

The Zimbabwean liberation war is considered one of the classics in guerrilla warfare.

Embedding themselves among the peasantry, using herdboys as scouts and black security force operatives as moles, the two armies created “liberated zones” out of territories they captured.

From here they launched attacks.

By 1979 the Rhodesian government of Ian Smith had been forced to the table.

The Lancaster House talks, overseen by the UK government, resulted in a cease-fire and Smith agreeing to surrender power.

If you go to Zimbabwe today you will meet males born in 1979 and 1980 who are named Surrender in honour of that day on December 21 when the Lancaster House Agreement was signed.

Inasmuch as Mugabe’s revolutionary prowess is fabled, so is his ruthlessness.

Legend abounds about how he had a hand in the mysterious deaths of many Zanu leaders as he made his way to the top.

One of these was Josiah Magama Tongogara, the commander of Zanla. Tongogara was highly popular among the soldiers, the Zanu rank and file, and even among the people back home.

So popular that Mugabe is said to have preferred he not be around when independence day came, lest he be seen as an alternative.

A widespread (and believed) rumour is that Mugabe used to see the ghost of Tongogara every night at State House, compelling him to build a plush new mansion to sleep in.

On a mass scale there was the killing of more than 20 000 civilians in Matebeleland during the Gukurahundi campaign, a heavy-handed military operation to suppress a low-key insurgency.

And it was the good Mugabe in the good decade who ordered this heartless massacre.

Those who wanted to see only the good in Mugabe point to his stewardship of the country and its economy in the first decade of independence.

During that decade Zimbabwe was a net exporter of food and the government’s investment in education – including adult education – was reaping amazing results in terms of literacy and numeracy.

Despite pressure from the apartheid enemy down south, the economy was sound.

Art thrived, with Harare being a much-visited home of musical, literary and other cultural festivals.

On the streets of the big cities books from the dynamic publishing industry were as readily available as penis enlargement pamphlets at South African traffic lights.

At some point Mugabe went rogue. Many blame the 1992 death of his wife, Sally, who was a rock by his side and kept him in check when his natural lust for power got the better of him.

This theory has it that Grace, the woman who took her place, complemented his baser instincts.

That she played to his insecurities that had developed during his days as a wimpish schoolboy who was bullied.

This may sound a sexist view as it absolves him but there is no denying the correlation between his descent into outright villainy and the presence of his degenerate spouse.

When he died on Friday in a hospital in Singapore Mugabe left behind a country in ruins.

The economy is in tatters, the moral fabric of this once morally upright society has been torn by poverty and suffering.

Beneficiaries of Mugabe’s ambitious education polices – many of them highly educated professionals – work in menial blue-collar jobs around the world.

The Zimbabwe that Mugabe created as he became more and more paranoid is a repressive securostate where the military, the police and intelligence services are the real government.

His successor, Emmerson Mnangagwa, a protégé-turned-foe, will not fix the mess as he was a key Mugabe lieutenant during the years of destruction.

At his funeral African heads of state will applaud the life of a revolutionary, liberator, visionary and Pan Africanist.

None will mention the despot, narcissist, glutton and mass murderer.

TALK TO US

His legacy is one of shame. Instead of a hero he became a villain. How do you feel about his death?

SMS us on 35697 using the keyword MUGABE and tell us what you think. Please include your name and province. SMSes cost R1.50. By participating, you agree to receive occasional marketing material

| |||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||

Publications

Publications

Partners

Partners