Medicines that taste like strawberries or mangos, cutting edge trials on preventing TB in kids, measuring how children’s bodies take up TB medicines. In this World TB Day feature, Kathryn Cleary profiles the amazing research done by the Desmond Tutu TB Centre in Cape Town

The world marked TB Day on March 24 and, according to the World Health Organisation, this year’s theme is It’s Time – time to accelerate diagnosis, treatment, prevention and, overall, time to end tuberculosis (TB).

Ending TB, specifically ending TB in children, has long been the focus of the Desmond Tutu TB Centre (DTTC), part of Stellenbosch University’s faculty of health sciences.

Spotlight spoke to DTTC director Professor Anneke Hesseling, as well as Dr Megan Palmer, medical director at the centre’s pharmacokinetics unit, based at Brooklyn Chest Hospital, about some of the centre’s ground-breaking work in paediatric TB.

The unit at Brooklyn Chest Hospital

Tucked away in a neighbourhood in Brooklyn, one of Cape Town’s northern suburbs, is Brooklyn Chest Hospital, a provincial TB hospital that treats both adults and children, and is home to the DTTC’s paediatric pharmacokinetics research unit.

“We currently mostly do work around drug-resistant TB and pharmacokinetics,” says Palmer.

“Pharmacokinetics is basically the study of how a drug moves through a body. You drink a tablet, but your body handles each medicine in a different way.”

To perform pharmacokinetics, serial blood samples are taken from children over a 24-hour period to measure and monitor the drug concentration levels in the blood.

“This helps us to establish what the optimal doses of the treatment are, and whether we should dose kids differently according to weight, age, HIV status or nutritional status. A lot of the work that’s been done here has informed the doses of TB drugs that are used to treat MDR-TB [multidrug-resistant TB] in children around the world,” says Palmer.

“The pharmacokinetics work we do here is largely about ensuring that we use drugs that are safe for children, that we use drugs at the correct doses to minimise side effects, that the drugs we use are effective and the children can actually get cured or manage to complete the treatment, and that there is also a lot of work on formulations.”

One in 10 cases are in kids

“TB is a disease of poverty and, statistically, one out of every 10 cases of TB occurs in children, but drug companies are not really interested in the paediatric TB drug market,” says Hesseling.

Part of the DTTC’s work is to engage with pharmaceutical companies on how to create child-friendly formulations.

Celebrations were in order last October after Unitaid – a multinational organisation that invests in innovations relating to HIV/Aids, TB and malaria – awarded the DTTC with a grant valued at more than R280 million to develop and evaluate child-friendly treatments and preventative therapies for MDR-TB.

The grant will support the Better Evidence and Formulations for Improved MDR-TB Treatment for Children (Benefit Kids) project, which will run until 2022.

“[The study] aims to address research gaps related to high priority second-line TB drugs. These are the drugs that are used to treat and prevent MDR-TB. This is a big project that is made up of several smaller studies, trials and projects,” says Palmer.

The project will be implemented in India, the Philippines and South Africa.

“Children with drug-resistant TB are a neglected population and estimates are that about 95% of children [globally] with drug-resistant TB never access treatment, and the treatment we use in children is often just extrapolated for what we use in adults,” says Palmer.

Not small adults

“Children are not small adults; they metabolise differently and the drugs work differently in children, so it’s really important to generate data safely from children so that we can really inform which treatments are safe to be used.”

Palmer tells Spotlight that originally children with MDR-TB had to be treated for up to 18 months, and most of the time this required hospitalisation and daily, painful injections.

“Injections are painful, but they can also cause a significant amount of hearing loss as a side effect. Historically, children were admitted here at Brooklyn Chest Hospital for almost the duration of their treatment. [They were] separated from families, admitted in hospital for up to 18 months, [had] daily injections, and that’s just not good enough,” she says.

“So over the years, and with contributions from the studies we’ve implemented here at DTTC and work that’s happened around the world, South Africa has moved away from that so that most children receive shorter MDR-TB treatment regimens, without the need for daily injections and their unacceptable side effects, and many children can be treated at home.

“Everything we’re doing now is addressing a major knowledge gap,” says Hesseling.

TB Champ

TB Champ is one of the clinical trials under the Benefit Kids project, and looks at preventing MDR-TB in children under the age of five. It is only testing one drug, the antibiotic levofloxacin.

“Preventing TB is far more effective than treating TB, particularly from a public health perspective, so this is an important trial,” says Palmer.

According to Hesseling, no clinical trial has ever been done on preventing drug-resistant TB in children, and, as a result, there is no evidence to guide international and national recommendations.

“Prevention is much more cost-effective than cure,” adds Hesseling.

Treating MDR-TB is more complicated than treating drug-sensitive TB and includes more medicines and possible hospitalisation, all of which can be avoided if the disease is prevented.

“One of 20 kids in South Africa who get TB, get drug-resistant TB,” says Hesseling.

Study 35

“Prevention is better than cure”, says Hesseling, “but prevention needs to be feasible.”

In October last year, the DTTC launched Study 35, a preventative study that looks at using a shorter treatment regimen and a new combination of drugs to prevent drug-sensitive TB in children under the age of 12.

“I think a really important area for prevention currently is looking at shorter ways to prevent drug-susceptible [drug-sensitive] TB in kids, and also ways to prevent drug-resistant [MDR/extensively drug-resistant] TB in kids, so that’s an area where we are doing quite a lot of research,” says Hesseling.

“The standard [for preventing drug-sensitive TB] has been to give six months of isoniazid therapy, [but] the uptake is extremely poor and of the kids that start the regimen, fewer than 20% will go past month two. In essence, it really is not easily implemented.”

Study 35 is about short-course preventative therapy for drug-sensitive TB in children, which Hesseling says has already been shown to work well in adults. Instead of six months of daily treatment, Study 35 trials 12 doses of preventative therapy, a once-a-week medication over the course of three months.

“Getting an antibiotic into a child every day for six months is not fun, so a new regimen [that’s] been tested, evaluated and done really well in adults and kids is called 3HP,” says Hesseling.

3HP is a combination of isoniazid and rifapentine, and when given as 12 doses over three months it has been shown to be safer and just as effective as the six-month daily treatment of isoniazid.

“The idea is that it would really improve the uptake of the prevention regimen so that kids can actually take it.

“What we need to know in general then is how to get this into kids. We need a formulation or a form of the pill that kids can take like a tablet, and we need to know what dose you give to children and how safe it is,” she adds.

Making medicines taste better

As part of the DTTC’s clinical trials, studies and pharmacokinetics work, new drug formulations are being investigated for both the prevention and treatment of MDR-TB.

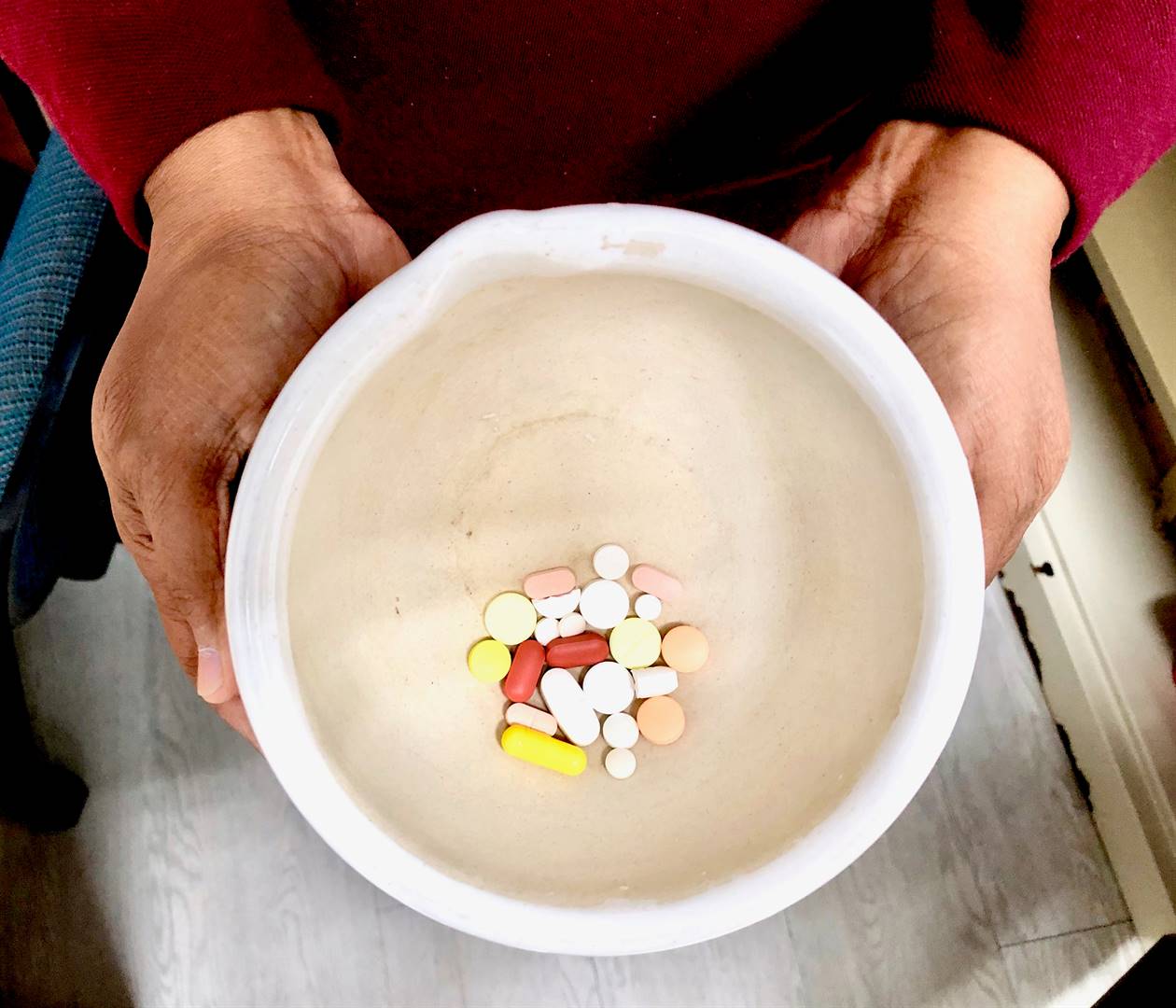

“A lot of these medicines are adult drugs that are crushed and mixed in yoghurt or water, or the children have to chew them and they taste bitter and horrible, so some of the work we do here is to work with pharmaceutical companies to look at formulations that are child-friendly and that taste nice,” says Palmer.

The DTTC teams have pushed towards making TB prevention and treatment more child-friendly for years. Their child-sensitive and child-focused staff have worked in partnership with their social science team to improve TB care for children.

DTTC’s social science team has worked in Brooklyn Chest to interview children, caregivers and parents on the type of medicines children like and don’t like to take, as well as what the experience of being hospitalised is like and how it could be improved.

“We’re hoping to be able to also contribute evidence about how to make things more child-friendly,” says Palmer.

Based at the BCH research unit, study nurse Adelaide Carelse said the new medications DTTC were developing had a much higher approval rate by children, and were easily dispersible in water.

“The medication that is on the market now doesn’t taste nice,” said Carelse.

“The children don’t want to drink it and get nauseous. The new medication we are developing tastes like maybe strawberry or mango, and [the kids] take that medication better,” says Carelse.

“We might crush it and mix it with water. In most of the trials we’re doing now we have to mix it with a certain amount of water, versus the old drugs, [which we had] crush and mix it with maybe yoghurt or juice to a better taste,” adds Carelse.

Inside the ward

Study nurse Ragmat Saul gave Spotlight a tour of the research unit’s patient ward.

Before entering the ward, Spotlight’s journalist was given a mask. According to Saul, the research unit has not yet suffered a shortage of masks in light of the Covid-19 coronavirus pandemic.

The ward is small, with five patient beds and one separate isolation bed. Children’s cartoon characters adorn the light yellow walls of the ward, and one patient and their family were quietly playing in the ward’s adjoining family room.

“I love working here because I can see when they’re giving the patients the medication it really helps the kids,” says Saul.

“We also test their blood and you can see there are results; the patients are getting better and we can move forward. I think that if they do go on with [the research work], TB won’t exist in a few years’ time.

“[The families] are always happy with the treatment here; they always say that they’re happy with the study we are doing,” says Saul.

She adds that children seem to be responding well to the new child-friendly formulations.

“Giving it a thumbs up,” she says with a smile.

Hope for the future

“In the past 10 years, we’ve probably made more progress than in the past 50 years with regards to TB therapeutics,” says Palmer.

“We do have some new drugs to treat drug-resistant TB – bedaquiline, delamanid – which are both highly efficacious. So if you have drugs that are stronger, then you might be able to kill the organism quicker and treat for shorter periods. These new drugs, which have also been trialled here, are one of the reasons that treatment regimens in adults and children have been shortened.”

“I would say we are finally gaining ground in TB, but it’s taken a long time and it’s been a disease that’s been largely neglected.”

This article was produced by Spotlight, an online publication monitoring South Africa’s response to TB and HIV

Publications

Publications

Partners

Partners