For 150km in Mpumalanga, the ruins of the Bakoni lie like figurative gravestones, marking a culture that fell from prosperity to extinction in little more than a generation, writes Luke Alfred

One of contemporary archaeology’s better-kept secrets concerns a group of people called the Bakoni who lived in the Mpumalanga Middleveld region between 1500 and 1820.

By all accounts, the Bakoni (roughly translated as People from the North) were a peaceable and industrious lot, who numbered 65 000 at the height of their powers.

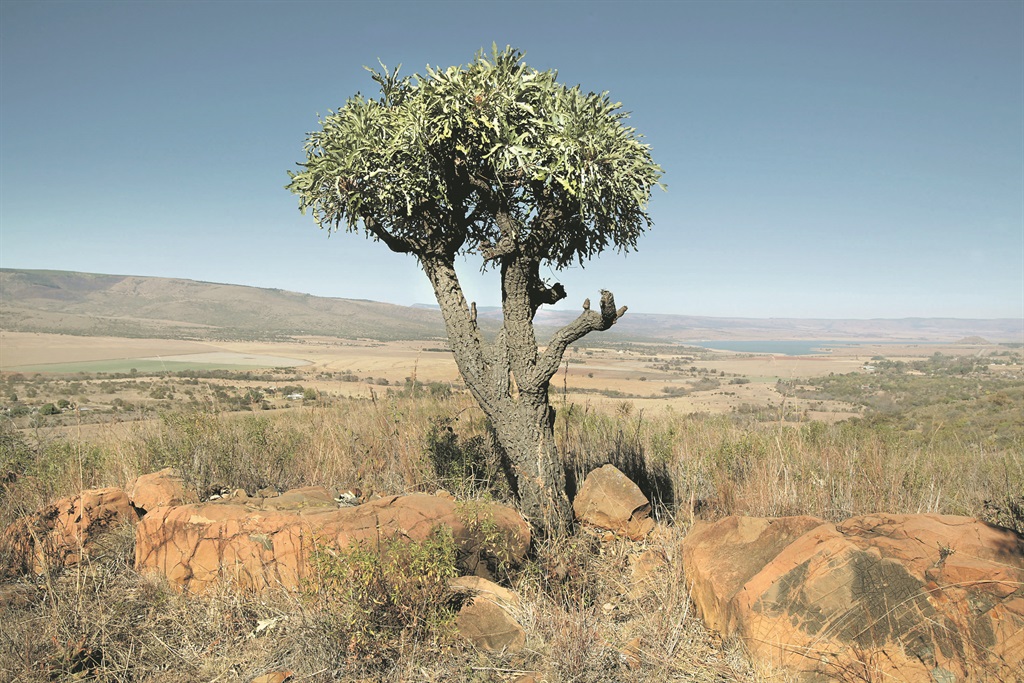

They built stone kraals and terraces, and cattle and goat pathways, which are scattered generously across Mpumalanga in a rough 150km line stretching from Ohrigstad on the edge of the escarpment in the north to Carolina in the south.

Their ruins and terraces are so ridiculously widespread that you can casually catch sightings of the formations through the car window while speeding along the N4 outside of Machadodorp on the road to Nelspruit.

Look carefully at almost any hill or koppie in the area and you will see the lines of stone walls, circular kraals and grassed-over terraces. Winter is the best time to see the ruins because the grass is low and the veld is burnt in places.

Smart farmers and adventurous chefs

The ruins suggest the existence of a flourishing precolonial culture and what the Bakoni bequeathed us is a massive open-air museum spread across hundreds of square kilometres.

However, outside of local landowners and a group of academic historians, archaeologists and geographers, the Bakoni’s story remains largely untold.

Currently neglected by dysfunctional provincial heritage authorities and stigmatised for years by an apartheid world view that saw them as static and backward, their story of enterprise and endeavour with a tragic twist is past due for the telling.

Here was a society that recognised, for instance, that they could prolong their growing season if they stayed away from the winter frosts of the Highveld and planted in the intermediate zone called the Middleveld.

They built their kraals and terraces on east and south-facing hillsides close to water, but far enough away to avoid flooding.

They kept cattle in stone pens close to where they lived and drove them to grazing along stone-lined cattle roads, fertilising the terraced fields with cattle and goat dung.

They were assiduous recyclers long before it became fashionable.

The fields themselves, often ingeniously built, constituted massive outdoor exercises in water filtration, the terracing preventing erosion and preserving moisture.

The rich volcanic soil contained everything from sorghum and millet to pumpkin, squash, peanuts and wild spinach. Supplemented by meat, food was flavourful and various.

Peter Delius, a Wits University historian who has studied the Bakoni, has found evidence of more than 20 recipes for cooking and preparing sorghum porridge.

This is a culture that appears to have been far more industrious and creative than they’ve been given credit for.

Their farming was intensive and their crop rotation was smart. On the moderate slopes of the Middleveld, they might have had a growing season almost eight months long.

A tale of enterprise and tragedy

One of the finest preserved examples of Bakoni ingenuity stands on Eric and Heidi Johnson’s farm Verlorenkloof, which is close to the Kwena Dam south of Mashishing (formerly Lydenburg).

Beyond the little graveyard of the Dutch Ahlers family and a slightly larger cemetery containing members of the local black community who work on the farm, there is a fine example of terracing that is hundreds of years old.

Supported by a 2m-high retaining wall both buttressed and scalloped, the terrace is remarkably well preserved.

The walls themselves are constructed with care and forethought; they contain a kind of pre-wall made up of a line of vertical rocks before giving way to the wall itself, which is often thick and varies in height.

Although the terraces are functional, they are not purely so. This is a beautiful, peaceful space.

“The work here may have been done for a family that was socially elevated,” says Eric Johnson.

While the Bakoni were savvy in taking advantage of local physical conditions and temperatures, their culture also prospered because it was at the crossroads of a far-reaching trade network.

The area exported gold and ivory to Portuguese and Arab traders, who shipped it off the east coast, probably from ports in what is now Mozambique. In return, they imported iron, beadwork and cloth.

While initially advantageous, the fact that the Bakoni were situated at the junction of trade routes flowing to all four points of the compass ultimately led to their undoing.

The riddle of their decline

The academics and researchers aren’t completely sure – there is a fair amount of spirited guesswork where Bakoni history is concerned – but the prevailing view is that they got caught between marauding Pedi from the north and Swazi raiders from the south.

They were ultimately unable to defend themselves in the ensuing Mfecane slaughter.

According to Joseph Mothupi, Johnson’s right-hand man and guide to relics on the farm, the Bakoni fought at least one pitched battle in the vicinity of Mashishing, but were unable to defend themselves for a prolonged period of time.

Perhaps this had to do with the comparative looseness of their social organisation or a distaste for combat. Maybe their reluctance was metaphysical – they simply wanted to be left alone.

The riddle of their decline – and, in some cases, reabsorption into other tribes – looks no closer to being solved now than it was 100 years ago.

With the Mfecane in full, blood-curdling swing, academics have suggested that, as a pre-emptive defensive move, the Bakoni retreated out of the sun-rich valleys and into the kloofs.

While this offered protection, the forests limited their crops’ access to sunlight, and therefore affected the stability of their food stocks.

This, possibly combined with successive years of drought, meant that, by 1825, the Bakoni were mortally wounded.

By then, many of their women and children had been captured by other tribes, including the Swazis, Ndebeles and Pedis, while their men had either fled or were dead.

The stone circles and terracing we see on the landscape are not only once-functional material remains, but figurative gravestones, a long and melancholy lyric to a culture that fell from prosperity to extinction in little more than a generation.

Nowhere is this better illustrated than on the Johnson’s farm. In the lee of towering orange cliffs and once camouflaged by hacked-away trees is a corbelled, once moss-covered hut with a tiny, ground-level entrance that looks more suited to children than adults.

There are many such huts scattered across the landscape, but the one on the farm is uniquely well preserved.

“We tie ourselves in knots over the corbelled hut,” says Delius, noting later that such huts were probably lookout posts with fine long views up the Badfontein valley.

“Though they may well have had a range of functions,” he says.

The hut, therefore, is both the actualisation and the symbol of a culture in retreat. In a sense, whether it was a granary, a smelter (unlikely), a lookout or a shelter is immaterial. Within only a handful of years, this retreat became permanent.

“The Bakoni were caught in a kind of no-man’s land between the Pedi and Swazi, and were subdued completely,” says Delius. “Radical depopulation of the area was complete by about 1830.”

Such a retreat was probably exacerbated by the arrival of the trekboers in the northern reaches of the area in the 1840s.

The neglect of the Bakoni

The neglect of the troubled Bakoni continues to this day, a neglect sharpened by the fact that issues of restitution rather than heritage and preservation have hurtled to the forefront of the national debate about land and land ownership.

When it comes to restitution, the Bakoni’s fate is complicated. Firstly, their dispossession took place roughly 100 years before the Natives Land Act of 1913, which is seen as the marker before which claims for land restitution (in the Restitution of Land Rights Amendment Act) cannot be made.

Secondly, with historical uncertainty about whether they constitute a tribe, a series of social groupings or a series of disparate but linked clans, comes confusion about where they stand in terms of restitution.

“In a sense, they’ve suffered a double tragedy,” says Delius.

“Not only do they exist no more, but, after 1994, the legal advice offered to them was for them to lodge their claims as a community – which has proven to be counterproductive.”

Bakoni heritage is theoretically protected by the Heritage Act, but, practically, the Mpumalanga Heritage Resources Authority doesn’t appear to have any interest in protecting any of the hundreds of Bakoni structures scattered across the Ohrigstad to Carolina cradle.

Landowners, academics and interested groups stand in opposition to such bureaucratic blindness, but they are hard-pressed to make inroads amid the apathy for the Bakoni.

Their rear-guard action for recognition and funding is increasingly desperate.

Where you can touch the walls of history

Beyond debates about restitution and heritage, progress in putting flesh to the bones of the Bakoni story is slow.

Delius, for example, doubts that oral history will provide the key to unlocking the treasure that is the Bakoni’s ingenious past.

Mothupi says that, even on the Verlorenkloof farm itself, there is need for further investigation because knowledge is incomplete.

Although they are thrilled with what has so far been discovered, everyone involved with the enigma of the Bakoni and their rapid disappearance is also painfully aware of what they do not or cannot know.

Then again, we have one of the world’s great open-air museums in the Bakoni’s stone remains. You can touch the walls and walk the terraces in a wonderland that allows you to step into a completely different time.

However, this wonderland is being encroached upon. Delius points to a potential mining boom in the area, particularly when it comes to chrome and platinum.

With a possible boom comes a frenzy for permits and prospecting by those with little regard for the Bakoni’s tortured past.

Should the opportunity arise, they will further profane these sites that are an irreplaceable part of our shared history.

TELL OUR STORY

You, our readers, are the most important part of the Our Land project. We would like you to tell us your stories so that we can share them across our partner network

Email us on ourland@citypress.co.za

Publications

Publications

Partners

Partners