It can take anything from several decades to a thousand years to grow a centimetre of topsoil and healthy soil is vital to a resilient, food-secure country, writes Mandi Smallhorne.

The dust storm engulfing the Kraft family on the national road as they drove home from their January 2016 Free State holiday was so thick they couldn’t see two metres ahead; they were forced to pull into a garage and wait it out.

The dust clouds barrelling across the parched province’s fields, which should have been green with maize at least waist-high, were reminiscent of scenes from the Dust Bowl disaster in the US during the 1930s.

Back home in Johannesburg, their neighbour, a soil scientist, showed them the red dust that had settled on his patio: “That’s Free State fines,” he said, using a term for a kind of topsoil.

THE LIFE UNDER US

Topsoil is the top layer of the soil – it can be anything from centimetres to metres deep – in which life happens; the roots of plants burrow deep, sending out fine, furry side branches that interact with bacteria, insects and fungi in the soil.

These are the living creatures that break down organic matter (such as manure) and minerals and enable the plant to feed on them.

Under natural conditions, this dense matting of roots and microorganisms also stabilises the soil, and the spongy nature of good, healthy topsoil soaks up rainfall, reducing the risk of floods, retaining water just where plants need it and boosting the storage of groundwater.

One other vital service that healthy topsoil performs is that it is full of carbon. Organic carbon, says Hendrik Smith, a soil scientist at Grain SA, is “the fabric of healthy soils”.

So there is a win-win equation here – if we can store more carbon in our soil, we will have healthier and more resilient soil, and we will be acting to counter climate change as well.

When human activities disturb the soil, via actions such as overgrazing, land clearing or continuous monoculture cropping, the topsoil becomes very susceptible to water and wind erosion, says Garry Paterson, a soil scientist at the Agricultural Research Council’s (ARC’s) Institute for Soil, Wind and Climate.

And when, as happened in the Free State from 2014 to last year, you add to the mix a prolonged drought and high temperatures that desiccate plants and suck all moisture from the soil, conditions are ripe for the dense dust storms the Krafts saw.

Storms whip up the precious topsoil and can deposit it far away (during Dust Bowl storms in the Midwest, topsoil travelled half a continent across the US to land in thick layers on ships in the New York Harbour).

LOSING THE LIFE

12 - The percentage of South Africa’s land that is suitable for crop production

13 - The number of tons, as a raw average, of topsoil we lose for each hectare of maize harvested

70 - The percentage of South Africa’s land that is only suitable for livestock and wildlife grazing

26 - The percentage of high-potential arable soil lost to mining and prospecting in mpumalanga by 2012

Topsoil is life; it is what grows our food, whether in the form of the plants we eat or the plants that feed our livestock.

It can be considered a nonrenewable resource; under natural conditions, it can take anything from several decades to a thousand years to grow a centimetre of topsoil.

Smith says we are losing it much faster than it is produced naturally, to windstorms, erosion and other land uses.

In South Africa, it’s often said we lose 13 tons of topsoil per hectare of maize harvested, but that’s a raw average. Paterson says losses range from five tons to 25 tons in some of the more fragile areas.

“If you look at satellite photos after heavy rains, you can see brown stains spreading out into the ocean – that’s silt and minerals washed down our rivers.”

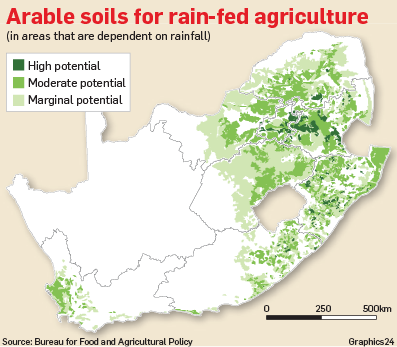

We don’t have much land to play with in the first place. Of the approximately 1.2km2 million that is South Africa, only 12% is suitable for crop production – and less than a quarter of that (22%) is high-potential arable land.

Water is the main constraint; Paterson says there is good soil for agriculture in parts of the North West and north-western Free State provinces, if only there was water available.

Close to 70% of our land area is suitable only for grazing, be it for wildlife or livestock.

Quite a significant chunk of land that is good for farming could be considered precarious, either in Mpumalanga where it lies over highly desirable underground coal seams, or in a rapidly urbanising areas.

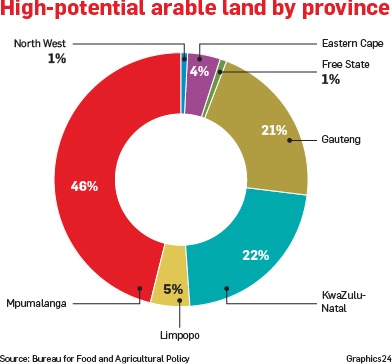

Paterson points out that “although it’s the smallest of the provinces, Gauteng has the highest percentage of good soils”.

At present, however, there’s still good open farming land on the outskirts of Gauteng worth preserving – towards Bapsfontein or Vereeniging and Carletonville, for instance.

According to a Bureau for Food and Agricultural Policy pilot study back in 2012, 46.4% of our high-potential arable soils are in Mpumalanga.

“The potential loss of maize production from current mining activities and activities in the near future amounts to 284 844 tons per annum.

A further 162 736 tons of maize could be lost from the prospecting areas that in future could also be transformed,” the authors write, calculating that this could over time push the price of maize and mealie meal up significantly.

Mpumalanga can be seen as food security insurance for South Africa because it is resilient to drought – and a changing climate means we’ll be seeing more droughts in future.

The sad news is that “high-potential soils that are mined will never be rehabilitated”.

At the time the study was done, Mpumalanga had probably already lost about 26% (225 217ha) of its high-potential arable soils to mining and prospecting.

And it can’t really be restored: “It’s like putting a wedding cake in a tumble drier and then trying to make use of what comes out,” says Paterson.

Contrary to earlier beliefs, you can’t replace topsoil, and the damage done by opencast mining to the water table compounds the overall damage to agricultural potential.

WHAT WE CAN DO

If our soil is so crucial and so hard won, is there anything we can do to save it?

Yes, as it happens, quite a lot.

First, we can use the extensive information that is available from the ARC and other organisations to assess the land we’re considering buying or using – is agriculture feasible, and what kind? Would mining or development destroy good soil?

Secondly, we can demand more responsibility and accountability from our government.

Mining-affected communities, environmental social justice activists and even mining companies themselves have all demanded more stringent application of laws and regulations pertaining to the environment.

Civil society should understand that this could affect our food and water security too, and join them.

Thirdly, we can suggest that government tighten up on laws such as the Conservation of Agricultural Resources Act to include some kind of duty of care for farmers to protect the soil.

Finally, we can get behind organisations like the ARC and Grain SA in supporting the application of conservation agriculture.

This is a method of farming that does not plough up the land, tearing the topsoil; instead, it drills into the topsoil to drop individual seeds in relatively undisturbed soil.

It keeps a layer of mulch or growing plants on the land at all times and it looks to diversify farms, running livestock and planting a range of crops instead of just one.

Conservation agriculture not only preserves soil from erosion, it also actively grows topsoil. And that is something we are going to need in a precarious future.

Cocky Mokoka invested in a no-till plough in 2007 and switched his entire 1 000ha in the Vaal area to conservation agriculture, with 300ha under crops and livestock running on the rest.

“The secret is a cover crop,” he explains.

This prevents evaporation of precious moisture and if you choose the right cover crop, it can fix nitrogen in the soil, reducing your need for chemical fertilisers.

“And you need to plant diverse crops. You need to move away from this mono, mono, mono,” he adds, referring to huge swathes of land all under a single crop in regimented rows.

Initially it’s expensive to invest in the machines, but after a few years your input costs start to drop (less fertiliser, herbicides, pesticides and even diesel for your equipment) and your soil springs back to life. The little community of microorganisms and insects starts doing its job again, the soil retains water better, it stashes away carbon, and the whole ecosystem becomes more resilient

This feature is part of a journalism partnership called Our Land, between City Press, Rapport, Landbouweekblad and Code for Africa, to find the untold stories, air the debates, amplify the muted voices, do the research and, along the way, find equitable solutions to SA’s all-important land issue

This is the fourth feature in a science of land security series made possible with the support of the African Academy of Sciences

TELL OUR STORY

You, our readers, are the most important part of the Our Land project. We would like you to tell us your stories so that we can share them across our partner network. Email us on ourland@citypress.co.za

Publications

Publications

Partners

Partners