Eighteen years on from the racial attacks at Vryburg High School, Teresa Oakley-Smith looks at what has changed at the school and in the country

‘Racism is like a Cadillac,” Malcolm X said once. “They bring out a new model every year.”

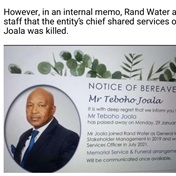

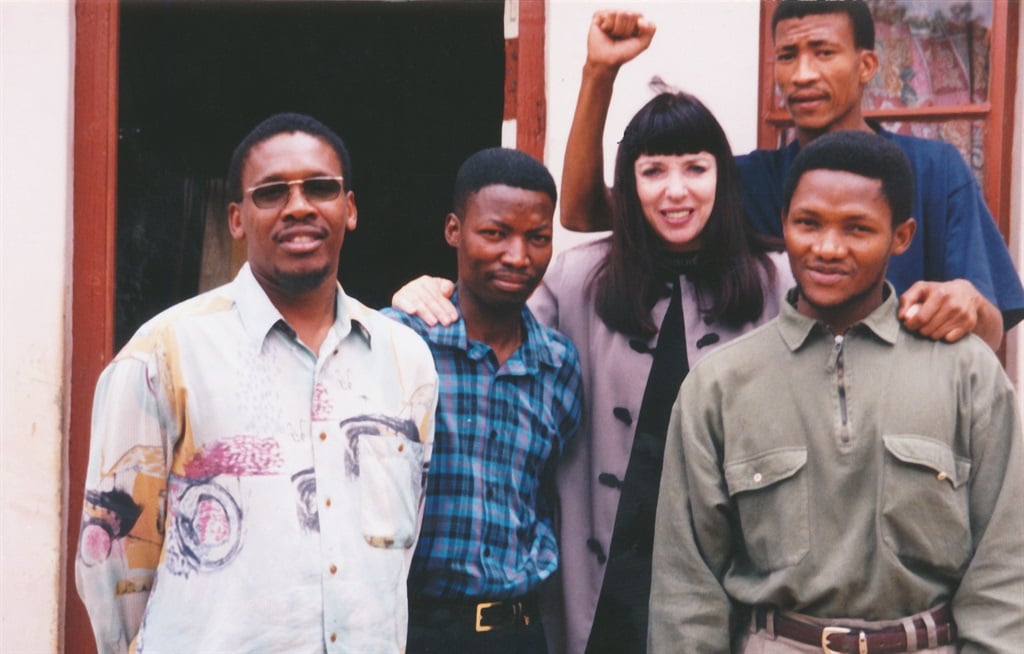

In 1998, I was appointed by the North West ANC provincial government to head a task team investigating the horrific racist attacks on black pupils at Vryburg High School.

Since then, I am often asked whether anything has changed at the school and the town that will be forever tainted with that memory.

The attack was the culmination of ongoing, insidious racism at work in the school and the town.

It ranged from the petty – in the dining hall, the table for black pupils was covered with a black cloth, the tables for white pupils with white – to the extreme, with black learners in the hostels living in frequent terror, awaiting beatings from white pupils and getting up before dawn to shower so that they would not be seen sharing facilities.

Black pupils were offered an inferior education. They were only allowed to study certain subjects in a system of so-called “parallel-medium education”, whereby white Afrikaans pupils were taught in Afrikaans by able, white, first-language speakers, while black pupils were taught by second-language speakers of English, some of whom were black.

No white pupils were taught by black teachers. There was virtually no social mixing between pupils or teachers, and racist taunts and epithets were common.

The (white) rugby team was well kitted out; the (black) football team had to pay for their own ball. Black pupils were forbidden access to some parts of the school grounds, such as the rose garden.

Most of the black pupils came from Huhudi township. The cost of travel, fees and uniforms was onerous. Most of these children owned only one white school shirt to be washed nightly, and it if was not dry and another colour shirt was worn, the pupil was severely punished.

What became of the ‘big five’?

The black pupils at Hoërskool Vryburg also became victims of a savage attack, orchestrated by a team of white parents, teachers, school governing body members and former pupils, allegedly led by the then deputy principal, a Meneer Steenkamp.

On one sunny day, an “English” classroom was invaded by sjambok- and chain-wielding assailants determined to “teach these k*****s a lesson and take back the school”. The school motto was, ironically, “Carpe Diem”. It still is.

Such overt and vicious racism is no longer a feature of Vryburg High, but the memories run deep in those affected, particularly the so-called “big five”.

These were five black pupils identified by the “concerned parents” as “troublemakers” and “no-hopers” destined for lives on the streets.

Clifford Shorane, Charles Nhlapo, Shadrack Bosman, Lengford Kelemetsi and Neville Mothikabele were the five, whose school days, like those of all black pupils at Vryburg High, were a living hell.

The media chose to focus not on them but on Andrew Babeile, an unfortunate young man who gained notoriety after the Vryburg incident by stabbing a white pupil in the neck at the tuck shop.

Contrary to all expectations, the big five are an unsung South African success story. All matriculated and are working today: two studied abroad; one is a doctor; some work in local government. Most are husbands and fathers.

They were brave enough to fight the injustices, tell their story and risk their lives.

Getting to the bottom of what happened, who was responsible and exactly how it was orchestrated, was extremely difficult. Our multilingual and multiracial team talked to everyone, from the local dominee and all the school staff, to the local police and shopkeepers, to many parents and, tellingly, the woman who cleaned the school.

Indeed, it was this brave woman, invisible to the people for whom she toiled, who overheard the plotting and planning by the deputy principal and his cohort of thugs and eventually, in the safety of a four-roomed Huhudi house, told us the story.

Unfortunately, most of our recommendations were never carried out and, in many ways, political scalp-saving prevailed over good judgement.

Instead of firing the deputy principal, the education department promoted him to principal of a Northern Cape school. The school principal kept his job. They continued with parallel-medium instruction and an all-white school governing body.

The protagonists of the shocking violence got off on a technicality. We reported the findings to the then premier, Popo Molefe, education MEC Zakes Tolo and even, in desperation, to then president Nelson Mandela, all to no avail.

I still find it incomprehensible that no effective action was taken against the perpetrators. Was bloodshed all right if it was black children’s blood?

Today, black children attend the school in greater numbers, but few of the teaching staff are black. The school is still “parallel medium”.

A cursory look at its website shows still largely segregated groups of pupils and few black teaching staff. Pictures of the matric dance show groups of white pupils together. The rugby team is white. The football team is black.

Black principal the only difference

The one recommendation the department did follow, and for which the school should be eternally grateful, is that they appointed an African man, Mandlenkosi “Barry” Fuleni, to the position of deputy principal.

Principled and full of integrity, he soldiered on through the aftermath. After 14 years as deputy principal, earning the respect of most pupils and staff, he applied for the vacant position of principal.

Unbelievably, some white parents then raised R2 million to take an application to the magistrates’ court to try to deny him the job. Even after two other (white) applicants dropped out to take up other posts, they continued to fight Fuleni in court.

Fortunately, they lost the case with costs and Fuleni was appointed. Under his stewardship, the school has gained the most success ever in matric (in 2015), with a 100% pass rate and many distinctions.

As white South Africans, we will never truly know what it is like to be the victims of racism, while our black counterparts still experience it every day in various guises, living “lives of quiet desperation”, as political analyst Sipho Seepe puts it.

There has been little development in Huhudi. The streets remain unpaved and the houses small and overpopulated. Black parents still struggle to find the money for Vryburg High’s uniforms, transport and fees.

Although black pupils are now in the majority, the powerful white parent caucus has ensured that black parents are not represented on the governing body and have no voice in the way the school is managed in 2016.

Eighteen years after the Vryburg fracas, and more than 20 years after our first democratic election, we still live separate, racially divided lives – apart from each other and fearful of each other.

Same-status contact is such a vital element of deracialising a society, and yet how many of us really know South Africans of other races? Yes, some of us are lucky enough to have our children schooling together, but to what extent do their parents socialise and share ideas and experiences?

How many black teachers, lecturers or professors do we find in these so-called nonracial schools and universities? Pitifully few.

Address racism systemically

The subtle messages are still strong and strident: White is superior, white is beautiful, white is clever. Black is inferior, black is corrupt, black is ugly.

Even more difficult to eradicate is the psychological damage caused to black South Africans by generations of discrimination. Somewhere deep down in the psyche of many blacks in Vryburg, Huhudi and elsewhere is a real sense of inferiority – just as in the psyche of whites there remains a real sense of superiority.

There seems to be profound apathy around racism too, a sense that it will always be with us.

Every so often an incident occurs that makes us react; then we carry on as before. Maybe we have an “antiracism day” and set up a committee to address the issue, but after a while, such efforts falter. Very few organisations, institutions or schools have a policy on racism, per se, instead referring to it under a host of ludicrous sobriquets such as “cultural diversity” or “human dignity”. No one seems able to call a spade a spade.

To really act against racism we need to address it systemically, recognising its foundation in the systems and economics of the places in which it entrenches itself. We need a process that incorporates the curriculum, role models, teacher selection and training; that involves school governing bodies and communities and includes rewards and sanctions.

Many white South Africans will remember going on “veld school”. Perhaps we need to incorporate a new form of veld schools into this process where antiracism replaces the old “swart gevaar”.

Current efforts at building nonracialism have failed because the unspoken message is “become like us and we will accept you”, as opposed to what it should be: “Be yourself and we will recognise our minority status, take a back seat and be guided by you.” The unspoken message has resulted in assimilation rather than genuine integration. It puts the onus on the victim to change in order to be accepted by the oppressor.

A genuinely transformed Vryburg High would have a majority of black pupils and black teachers, in line with North West’s demographics. It would have a majority black school governing body, be even-handed in its support for sports teams, and work at eradicating any vestiges of racism through its education. It would endeavour to support its poorest pupils by providing transport and uniforms, and reducing fees.

Perhaps it would celebrate a commemoration day every April to celebrate how far it has come from the days of April 1998.

Vryburg reflects the frustrating paradoxes that characterise South African life. Racism has changed its model but still governs our lives.

Yet despite the stubbornness of injustice, the best of our country lives on through the big five and people like Fuleni, who continue to fight, unsupported and unnoticed, one trying step at a time.

TALK TO US

What do you think is needed to ensure that Vryburg High School and places like it become fully integrated, and how should this be carried out?

SMS us on 35697 using the keyword VRYBURG and tell us what you think. Please include your name and province. SMSes cost R1.50

Publications

Publications

Partners

Partners