On paper, it is legal to be queer in Botswana, but that doesn’t match up with people’s lived experiences.

In tranquil Gaborone, Vukile Dlwati meets a veritable rainbow of LGBTI individuals who are living their lives despite an oppressive penal code and relentless homophobia in the workplace, the police, the church - and the healthcare system.

There is a sense of serenity when you land at Sir Seretse Khama International Airport in Gaborone that is a far cry from the mayhem of OR Tambo in Joburg.

Outside the airport, too, there seems to exist a heavenly landscape of laid-back people.

Botswana’s pula is stronger than the rand and the crime rate there is far lower than it is in South Africa.

There’s the death penalty, but citizens generally enjoy fundamental human rights, considerable free education, an Employment Act that does not allow for discrimination, free healthcare and a lot less race conflict.

But what if you’re queer?

A cursory check on Google reveals that it is legal in Botswana to openly identify as lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender or intersex (LGBTI), but your sex life is a crime.

Section 164 of the country’s penal code carries with it a maximum sentence of seven years in prison for “carnal knowledge of any person against the order of nature”.

MEETING CAINE

“Sometimes it feels like you’re in paradise, sometimes it feels like you’re in prison.”

The sun is baking down on the taxi as it heads into the suburbs of Gaborone.

There are no signs outside the double-storey house to indicate that we have arrived at the office of the outspoken advocacy group Lesbians, Gays and Bisexuals of Botswana (Legabibo).

Inside, it’s a different picture. Upstairs, sitting opposite manager Caine Youngman, I ask about the contradiction in the law, which is a fairly common one across the continent.

In plain English, he says, any person involved in a sexual act that doesn’t involve a penis and a vagina is guilty of a criminal offence.

“The penal code is perceived as a law against the gay people,” he says, a frown creasing his forehead.

"It’s unimaginable, according to conservative social norms, that heterosexual couples would enjoy anal sex, oral sex or use sex toys, so there’s no reason to believe that they would do anything against the “order of nature”.

“Botswana is a secretive nation … Issues like this don’t get addressed,” he says.

The penal code breeds further secrecy, shame and victimisation among the LGBTI community.

There is a widespread need to avoid being stigmatised by your family, your workplace and the state.

“Take nurses for example,” says Caine.

“They have the wrong interpretation of the law … They believe that providing healthcare services to us makes them complicit in breaking the law because of the penal code.

"Or at work – you basically become unemployable once you take your matter to court and seek justice.”

The activist says change is slow in Botswana, and the problems that haunt the LGBTI community often lead to mental illness, and drug and alcohol abuse.

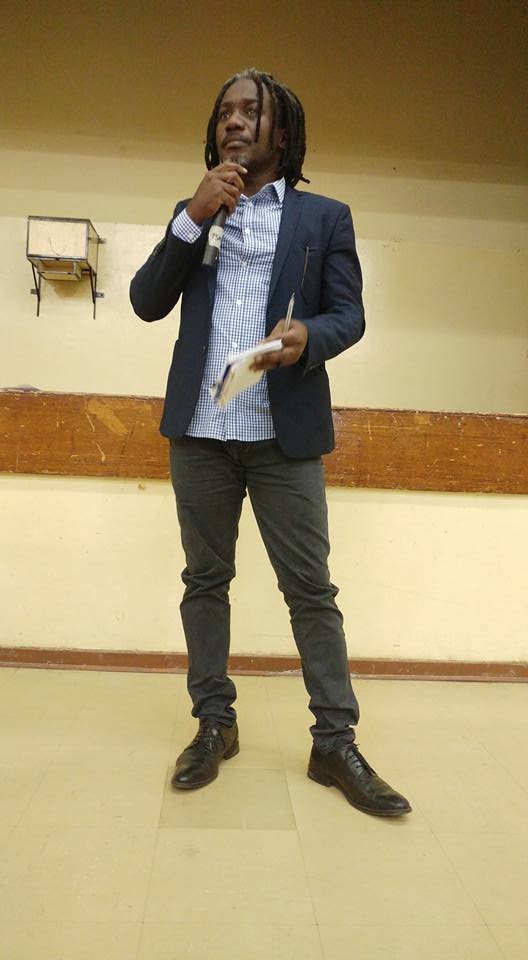

“Sometimes it feels like you’re in paradise, sometimes it feels like you’re in prison and sometimes one can be dazed,” he says, pensively stroking his impeccably groomed dreads.

MEETING KAT

“Here, you’re not special, but the abuse is special to you.”

After spending some time with an animated Katlego Kolanyane-Kesupile, I’m not surprised by how often our conversation is interrupted by people stopping to greet her.

“Oh, in Gaborone everyone pretty much knows everyone,” she says, fixing her bold maroon panama hat and neatly dismissing the compliment.

Kat, as she is fondly known, is an “artivist” because she uses art to advocate for the rights of LGBTI Africans.

One thing you have to know about her is that she doesn’t leave the house without sunglasses because, as a transgender woman, she picks up a lot of optical violence.

“Botswana people are beautifully passive-aggressive,” she says over drinks at Europa in one of Gaborone’s malls.

But she doesn’t just get stared at – people also verbally threaten her.

I ask her about the penal code and she snorts: “You could be a celibate gay man here, but you are still a criminal in their eyes by virtue of you being gay, because you want to have sex in a certain way … You’re protected as a citizen, but only if you’re a particular kind of citizen.”

From the age of eight, Kat believed that she was a girl and that she would develop physiologically as a woman.

“Against all intelligence in my head, my body was supposed to grow boobs when I got to puberty ...

"But I am in this body and I recognised that what the world expected of my body is different from my expectation of my body.”

She says society is particularly cruel to trans people: “Here, you’re not special, but the abuse is special to you.”

There is no hate crime legislation, she says, so it’s difficult to report, for example, physical violence rooted in a certain type of hatred such as transphobia or homophobia.

Every trans person in Botswana has the right to free, quality healthcare, but transphobia makes it gruelling and your existence is reduced to the struggle of getting on to hormonal treatment as you transition.

“What do we think of trans women who need to go for a prostate exam?” she asks.

“Gender affirming surgery is not a matter of doing it to remove the prostate – you still have a prostate, but you get a vaginoplasty.

"Does that mean you don’t go for a prostate exam? And what happens when a trans man needs to get a cervical exam?

"We still look at cervical cancer as a woman’s thing. But cervical cancer is for people with cervices.”

MEETING ADVOCATE AND ROMEO

“Who is the man and who is the woman?”

I will hear similar stories from many people I interview in the sweltering city with its main streets named after Pan-African liberation heroes.

Back at the Legabibo office, lanky young volunteer Advocate says that the last place he wants to visit as a gay man is the hospital because of the sneering looks he gets from healthcare workers when he goes to test for HIV with his partner.

“We are often asked the wrong questions in hospital, like: ‘When was the last you had sex with a woman?’ The public health space is very heteronormative and you can’t open up.”

For him, it’s triggering because he struggled for years to accept that he was gay before eventually coming out to his grandmother, who raised him.

“It was really confusing having to fake being heterosexual … I volunteer here because I am willing to be there for someone who might be going through what I went through.”

Legabibo helped him see that there are others like him.

But just being a “normal” gay man is full of fears. The police, he says, are as bad as the nurses.

He recalls having to report his boyfriend at the police station when things started to get violent during an argument.

He had to give a statement to the police, who wanted to know about his relationship with his boyfriend who was in make-up that day because he was taking part in a local fashion show.

“They started questioning why my boyfriend was wearing make-up and dressed like a woman. Who is the man and who is the woman? It was a very terrible experience.”

I join Romeo Yame Kehitile, a peer outreach worker at Legabibo, who always knew he was gay.

He says people in his village and at high school used to insult him because of it.

“Today, I laugh at people who call me names, or at those who say we are cursed and that we are not normal,” says the confident 21-year-old nutrition and dietetics student.

He says that, throughout his life, he has experienced people using their religious and cultural beliefs to justify their homophobia.

“I go to church and people don’t say anything about my sexual orientation, but the preaching can be very homophobic …

"But God loves me and I believe he created me to be who I am. I kiss my boyfriend in public despite that it could be regarded as criminal to do so.

"Why can heterosexual people kiss and we can’t?” he asks defiantly.

MEETING RUDOLPH

“I was so scared to undress in front of the nurse.”

Rudolph does not feel safe using his real name for our interview. When I meet him at a pub, he eagerly introduces me to his girlfriend of seven years.

He speaks candidly, dressed simply in a maroon T-shirt, black leggings and chic Louis Vuitton shoes, but, throughout the conversation, his eyes glance nervously at whomever is sitting behinds us.

“I am a Motswana trans man. I was born female, but identify as a male; that’s who I am,” says Rudolph, who doesn’t take kindly to anyone referring to him as she.

Rudolph has turned to entrepreneurship because he says trans people are faced with discrimination and stigma in the job market, despite Botswana’s Employment Act forbidding discrimination based on gender, race and sexual orientation.

It sounds good on paper, he says, but not in reality.

“I know I didn’t make the cut for many jobs because I was discriminated against on the basis of my gender,” he says.

“For a start, my identity card says that I am female, but I present myself as male in the interview set-up.”

It’s the same at the clinic: “I remember a nurse attending to me once and she kept referring to me as ‘sir’ because of my appearance. She wanted to examine me. I was so scared to undress in front of her.”

Rudolph binds his breasts to pass as a man.

“I had to take off the muscle top and, as soon as I did, the nurse said: ‘Wait, I will be back!’”

Little did Rudolph know that she was going to call her colleagues to come and join her in ridiculing him for “pretending” to be a man.

“I was the laughing stock at the clinic and I decided to leave,” he says.

MEETING LADY KILLER

“Nobody gives a sh*t here! This place gives us comfort.”

Before I leave Botswana, I pay a visit to a nightclub called Zoom after being told it’s a safe space for Gaborone’s queer community.

Here, I meet Lady Killer.

Well, she’s hard to miss.

Her flamboyant dance moves, brow ring and a striking tribal tattoo on her right arm all vie for attention.

Lady Killer is a personal fitness trainer who has been an advocate for LGBTI rights for eight years in Botswana, and she’s eager to chat.

“Come!” she insists, leading me away from the dance floor and its electrifying neon lights to a quieter room filled with men playing pool.

Her biggest frustration, says Lady Killer, is the struggle to find a secure job because she’s openly lesbian.

At Zoom, she can forget about all that.

“Here, we are free to do anything. Nobody gives a sh*t here! This place gives us comfort.”

She says her heterosexual counterparts at Zoom just “don’t mind”.

In fact, a feature of Botswana is its tolerance and, according to her, the laws don’t match who Gaborone’s people really are in their hearts.

.This series on LGBTI life in Africa is made possible through a partnership with The Other Foundation. To learn more about its work, visit theotherfoundation.org

Publications

Publications

Partners

Partners