As South Africa celebrates a generation of freedom, Anglo American acknowledges its deep roots in the country and looks ahead to its contribution in the next 25 years and beyond.

Over the next five weeks experience 25 Reasons to Believe with City Press as we explore the economy, job creation, enterprise development, health, land reform, sustainability, education, technology and – most important of all – the communities

As you approach Anglo American’s iron ore business, Kumba Iron Ore’s Kolomela mine just outside Postmasburg in the Northern Cape, big blue safety boards line the road reminding employees to “work safely”.

Back in 2016, Kumba Iron Ore’s chief executive officer Themba Mkhwanazi launched a “sacred covenant code” and declared that no person would lose their life while working there.

It was no small commitment, considering the scope of its operations – the Sishen and Kolomela mines employ over 10 000 mine workers including contractors who are exposed to the elements during their work shifts to enable the mine to operate around the clock.

Philip Fourie, Kumba Iron Ore’s executive head of safety, health and environment, says: “Our goal is to achieve zero harm, but our focus at Kumba Iron Ore is to make the company fatality free first, and that will help us achieve not just zero harm, but absolute zero harm, because we consider even scrapes on the fingers as harm.”

The zero-harm approach is not just corporate talk and good PR for an industry that is constantly scrutinised for its safety record – it is something that is ingrained in every employee on the mine.

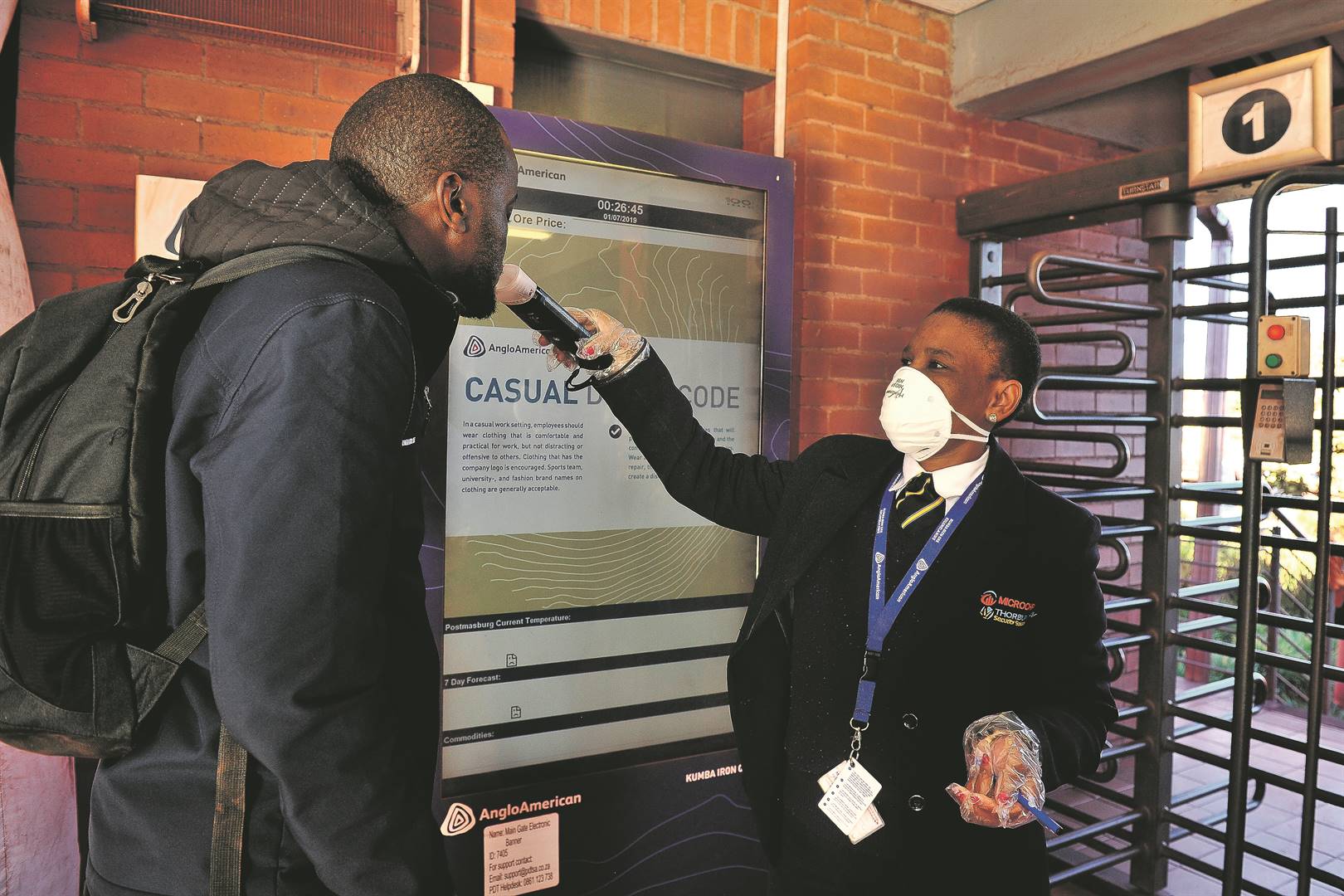

Everyone – including visitors – at all the Kumba Iron Ore offices and mines has to undergo a breathalyser test, every car when entering the premises has to be reverse parked, no one is allowed to walk and talk on a cellphone on any of its premises and, when you go up or down a staircase, you must hold on to the railing.

These four simple rules have been part of a bigger campaign that now sees Kumba Iron Ore achieving its longest period without a fatality.

“May 10 2016,” Fourie says, “that was when we had our last fatality.”

The hardest part, he says, has been the culture change within the company because there are more than 10 000 employees who all need to make sure that safety is not just the responsibility of management, but of every employee.

“Our employees mostly stay in environments that are typically not completely safe – they travel to work in taxis that are not completely safe and then they get to the mine and they need to change their entire way of thinking. That has been the challenge.”

Kumba Iron Ore’s approach to critical controls, its incentive programmes and its constant, in-your-face reminders have helped make their mines a safe environment to work in.

Some of the incentives the company has introduced include rewarding employees for reporting any work area they believe is unsafe.

“We sent out a personalised memo to every employee and contractor from our CEO stating that they must report any unsafe work as per section 23 [the right to stop unsafe work and to refuse working in an unsafe environment] breach if they feel unsafe, and that the CEO and management will fully back them,” Fourie says.

Previously, many employees didn’t report unsafe working environments mainly due to fear of victimisation or losing their jobs.

The department that implemented the best section 23 protocol was awarded a trophy and prizes.

Another incentive was the change in bonus structure. Previously, 70% of bonuses were awarded based on production and 30% on safety, but, since last year, this has changed so that bonuses are calculated on 50% production and 50% safety.

With critical control mechanisms put in place to make sure working environments are safe, leaders randomly check areas and make sure no short cuts are taken. These leaders are also trained and encouraged to genuinely care about their subordinates’ safety because, “if you do not truly care, employees will see right through that”, Fourie says.

TECHNOLOGY AND SAFETY

One of the strategies for better safety controls is the use of technology.

Fourie says that, “when it comes to technology in the safety environment, we want to employ as much technology as possible” because humans do make errors and take short cuts if they deem it easier for their work.

Some of the technology they have rolled out includes auto-braking systems, another first in South Africa.

“With auto-braking on our [big] mining vehicles, the vehicle will automatically stop and not collide with a person, vehicle or equipment.”

Another way to make sure critical controls are observed is biometric access to substations, where only technicians who are authorised and accredited can enter, thus eliminating the risk that an unauthorised person will be able to use a technician’s access card to gain entry to critical areas.

There are also collision warning systems that have been installed in all mine vehicles, while fatigue monitoring cameras – which track the eyes of operators and look for slow blinking and signs of tiredness – are used to make sure that all operators and drivers are fully fit to operate their equipment and vehicles.

Blasting and drilling have now also been made safer.

Recent scientific advancements mean that dynamite has become obsolete. Blasting is done when two chemicals combine – only in the hole, and only once all safety protocols have been completed.

Drilling is now done autonomously from an air-conditioned control room, where a driller sits in front of computer screens and monitors the drill’s vitals while using an Xbox gaming controller to adjust the drills if necessary.

“This all takes our people out of dangerous environments and makes sure they are safe,” Fourie says.

But the drillers aren’t the only ones who have gaming controllers. Automated bulldozers that move the rock and ore creating the mounds on mines are also being employed.

“An operator can now use a gaming controller to operate those, especially in high places. So, So if anything happens to the dozer, it is safe because we don’t have anyone in it,” Fourie says.

TECHNOLOGY, MINING’S FUTURE

Thinking about what a mine might look like in the future, Fourie says that as much as technology is the future, this does not mean that mines will be without people.

Through the company’s FutureSmart Mining™ programmes, it is exploring all the options to make mining more efficient in the future.

This doesn’t necessarily mean a loss of jobs, but rather opportunities to learn skills that are needed for the jobs of the future.

Tracking wellness

- Silica is still used in mines and, because of its health risks, mining companies must comply with many stringent regulations. Anglo American is starting to roll out monitors that track the level of silica and then automatically shut down a work area that exceeds this level.

- Fatigue is another aspect of an employee’s work life, and this is checked by fatigue monitoring cameras and by medical experts who review employees who work long hours.

If an employee is tired, they are hooked up to a state-of-the-art fatigue monitoring system, where they play a game that tests their cognitive ability and speed.

Their vital signs are also tested to pinpoint the exact cause of the fatigue. If the employee scores below a certain percentage, they are sent to a nap room, where they can sleep on a reclining couch for 20 to 25 minutes.

Acting supervisor of the centre, Annie Seleka, explains that, “if they sleep for longer than that, they enter deep sleep and become more tired and they won’t be able to function after that”.

The employee is then sent to the bathroom to splash some water on their face before moving on to a chill area for about 10 minutes. Here, the employee can read or play board games while a bright white light suppresses melatonin.

“This makes the brain cells more active – melatonin is the hormone that makes your brain sleep – and makes sure that they can function for the next three to four hours,” Seleka says.

- This centre is also kitted out with a gym, a pool area and a canteen that is open 24 hours a day. Elsewhere on the mine, there is a medical facility where employees can go and get their hearing and sight checked. There’s even a trauma unit on site.

Drones and X-boxes

UNDERGROUND WI-FI

At Anglo American’s Goedehoop and Zibulo Collieries in Mpumalanga, as well as Dishaba platinum mine in Limpopo, communication has been improved a thousandfold thanks to the installation of Wi-Fi infrastructure underground.

The coal mining sector previously had fixed lines installed, and mine workers had to travel long distances underground if they needed to make contact with the surface as telephones were not portable.

Adolph Nhlapo, engineering manager at Goedehoop Colliery, says: “Our people are now able to communicate in a manner that is effective and efficient because they can immediately contact the right person for a specific query [instead of going through an operator]. They can now also attach pictures and videos of the problem so that it can be solved faster because the expert can see the problem in real time.

“We can also use Wi-Fi capabilities to track where the equipment is and monitor it to reduce inefficiencies.”

The reason it has taken so long, he says, is because the infrastructure was just not available underground, and because of the cost and safety issues of the equipment. Costing in the region of R10 million, Nhlapo believes that, once rolled out to all of Anglo American’s operations, the cost will come down.

This underground Wi-Fi technology was piloted at Zibulo Colliery last year and has also been recently launched at Anglo American Platinum’s Amandelbult Complex’s Dishaba mine.

DRONES

Franco Grobler, the engineer for survey technology (AKA “head of drones”) at Kumba Iron Ore’s Kolomela mine in the Northern Cape, has been using drones for the past two years for pit mapping to create “3-D models to calculate how many tons we have mined and what we still can mine, and for making mosaics for planning purposes”.

Grobler says drones are used for equipment inspections and to prevent accidents as they can be equipped with thermal cameras and image sensors to detect overheating and defects in equipment.

Another use is to make sure blasting sites are safe ahead of detonation and to record data for the analytics team to use in their reports to management.

Grobler is confident drones will be commonplace in mines of the future, but is sceptical about some of the virtual reality innovations for them.

“We can use virtual reality, but, currently we are still investigating feasible applications,” he says, adding that they are constantly exploring what technology will or won’t work at a mine, and only use what will improve the mines’ production efficiencies and human safety.

The most tech’ed out place on the mine in Kolomela is the control room. As you enter, you hear the hum of computers working at high speed; there’s a huge monitor in front showing the live feeds from the pits and another with a 2-D map of all the pits.

This is where the robotic drill operators sit and where all the mine’s operations are managed from.

On each of the autonomous drillers’ desks sits an Xbox controller, an access control box, three monitors, and a keyboard and mouse. From this air-conditioned room, they can precisely drill double the number of holes than if they were actually on site, allowing for a faster, safer and more efficient process.

Ludi du Plooy, one of the managers in the control room, says that “the most important thing is that our people are taken out of the firing line and can operate equipment more effectively”.

Du Plooy says the operators have very little to do; they adjust their coordinates and settings, and only use the Xbox controllers for minor adjustments.

A big map in the centre of the control room tracks all haulers, trucks and equipment, while also managing the routes and pit health to ensure operations run smoothly.

“All our software is coded by third parties, but tailored for us,” he says. “Artificial intelligence is used where possible, but still leaves vital processes in the hands of the people in the control room.

“When technologies are released, we analyse it and, if it will improve our systems and management, we deploy it as soon as possible.”

Publications

Publications

Partners

Partners