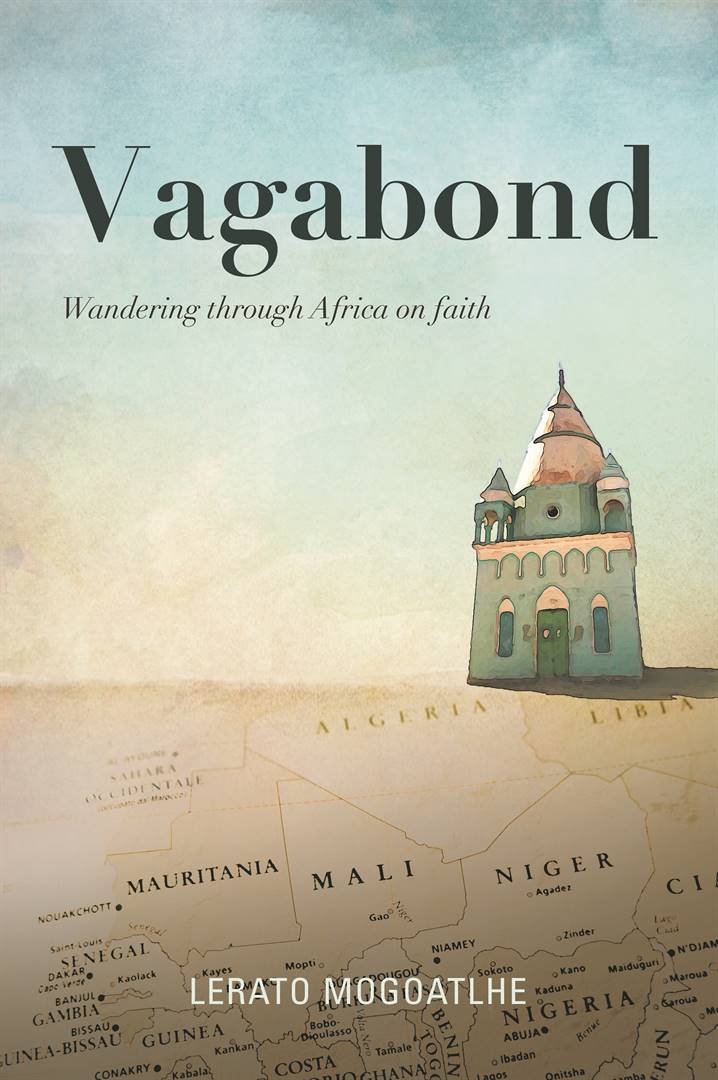

Vagabond – Wandering through Africa on faith by Lerato Mogoatlhe

Blackbird Books

264 pages

R250

Journalist Lerato Mogoatlhe travelled solo across 21 countries on the continent over a period of five years. In this extract from her travel memoir, Vagabond, Mogoatlhe’s chance encounter with Malian singer Habib Koité in a desert in west Africa has her living out her best life.

Essakane is a small village about two hours out of Timbuktu. It has a smattering of houses in different stages of crumbling, with missing door frames and walls that look like they were abandoned midway through the process of building them. An eerie silence keeps the village in a comatose state.

The trip is uneventful other than for the cars getting stuck in the sand. At the festival site, I stand on dunes to catch my breath; taking in hills of soft white sand that burn from the scorching sun. I make my way to the media camp, where the publicist’s only regret when I ask for a media pass is that they don’t have a mattress for me, only a thin sleeping mat. I share the tent with two journalists – one from the US and one from Argentina. The site has sections for sleeping that are divided into camps for the press and artists, a conference area and accommodation for everyone else, as well as bars and restaurants, bathrooms with showers and toilets, the market and the main stage area.

Before becoming a global event that brings more than 30 000 people to town, the Festival in the Desert was the traditional meeting place of the Tuareg tribes of the Sahara. Even with roots and families in villages like Essakane and towns like Timbuktu and Gao, Tuaregs are nomadic at heart and still follow a way of life inherited from ancestors who roamed the desert with their camels and livestock. Get-togethers like this one are the fabric of their social life.

The festival remains true to its heritage. Men and boys are dressed in bazin boubous, their faces wrapped as always in indigo cotton turbans called tagelmust. Women drape themselves with ?owing robes; their heads gleaming with gold accessories. Walking past the stage, I see Harouna Samake tuning his kamale ngoni; Salif Keita’s making a surprise appearance. I huff my way to the entertainment area to look for a good time. A short, very black man in a khaki suit and straw hat jumps at me, planting a kiss on each cheek.

“Mon chérie, join us, please,” he says, his right hand clasping my left.

His name is Djibril. He and his friends, Cherrif, Omar and Adama, have boxes of Marlboros and bottles of whisky on their table; of course I’ll join them. We barely understand each other – I don’t understand French, still, and Djibril’s English is worse than my French. I pretend to follow their conversation; laughing when they do and contributing by talking about how amazing the festival is. Our table falls silent, their eyes and bodies turning in the same direction. My jaw drops when I see who they’re looking at. He strolls between plastic tables, smiling at everyone who greets him. Habib Koité hugs everyone and sits opposite me. I walk over to him and fall at his feet the way people here do when they meet an icon.

‘That’s not necessary,’ he says, laughing.

“Habibo, this is our great friend from South Africa, Lerato,” Cherrif says.

“Lerato, this is our friend, Habib.”

Habib envelopes me with a long embrace and follows me back to my chair. He never leaves my side. He translates the conversation for me or starts one between us, encouraging me to use the growing French vocabulary that still struggles to roll o? my tongue. He holds my hands and shares secret jokes with me. More people join our table, some for a few minutes to greet Habib. I’m with my favourite artist and he is hanging on to every word of my seriously broken French; he thinks it’s amazing that I’m travelling around Africa.

“I hope you’re hungry,” he says after a while, pointing at an old man bending over a sheep. One sweeping slash and the sheep stops bleating. It bleeds out into a hole the old man digs for this purpose. He hangs the carcass on a tree to skin and gut it before putting it on a spit ?re. When it’s ready, he slices it, and we eat it with takoula.

Habib and I leave the gang to watch Salif Keita. He holds my hands to help me move up and down the dunes and o?ers me water whenever I stop to catch my breath. The area around the stage is already full. There are rows of people sitting on the ground at the front circled by the standing crowd. Habib is tall enough to see from the back; I’m happy as long as I’m with him. He uses his star power to cut through the crowd to take me to the front. My life is a fantasy – I’m with Habib Koité at a Salif Keita performance, and the band wink and smile when they spot me in the crowd. We go back to the gang after the performance, where the party moves inside. Whisky and beer make way for tequila shots, and the music goes from barely audible to full blast. The deejay makes my night when he plays Bobraba. It always inspires the most skanky-ass dance moves; I lay them on Habib, laughing, downing shots, dancing, becoming friends.

The festival by day is an open-air market with food, jewellery and fringe performances. A woman sits on the ground beating a drum, occasionally dipping her hand into a calabash with water, which she splashes on the drum’s hide. Other instruments in the performance are the clapping hands of three women in black chi?on wraps and cornrows styled with gold disks. A Tuareg boy in matching tan tunic and loose pants stands centre stage, his short arms spread away from his body. He jerks his shoulders and neck in rhythm to his left leg, which he holds in the air at a 45-degree angle. He breaks his gaze with a grin at the end of his performance.

Four coned, black leather hats lined with cowrie shells peek out from the top of a dune. I follow them, and discover that they belong to musicians who chant around the site and play a musical instrument made of calabashes. One hat has round mirrors, another is decked with blue, yellow, purple, pink and lime cowrie shells. There’s a camel parade and a traditional sword fight dance, with men moving slowly and gracefully in their grand boubous; my first time in the Sahara Desert remains one of the most enchanting times of my life.

Vagabond launches on Tuesday at Exclusive Books, Rosebank. Email marketing@jacana.co.za to reserve a spot

Publications

Publications

Partners

Partners