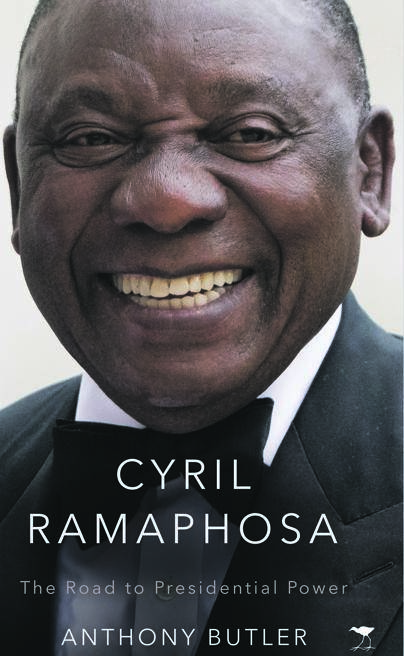

Cyril Ramaphosa: The Road to Presidential Power by Anthony Butler

Published by Jacana Media

Pages: 448

Price: R330

With the completion of the country's sixth general election last week, professor of political studies at the University of Cape Town, Anthony Butler, in this extract from an intricately woven biography of Cyril Ramaphosa, examine's the president's first term in office and predicts that the ANC 'will not see a new president until 2027', saying that the country's leader has 'not yet pushed the limits of his personal power'.

It is sometimes remarked that the personal characteristics one needs to ascend to the presidency differ quite markedly from the qualities one requires to succeed once one has secured the job. Indeed, some sceptics alarmingly believe that these two sets of qualities are mutually exclusive.

Anton Eberhard, a planning commissioner with whom Cyril Ramaphosa has since worked closely, notes: “It is a cruel irony that Ramaphosa, who potentially could become South Africa’s greatest president to date, has been dealt the worst possible hand: a paper-thin margin in a divided ANC, rent-seekers fighting back and an economic downturn following the disastrous Jacob Zuma years.”

The new president’s stabilisation programme began with the firing of a small number of Zuma’s most controversial ministers.

A key priority was the state-owned enterprises, which had been mismanaged and looted over the previous decade.

Corruption was meanwhile addressed by means of three commissions of inquiry into state capture, the revenue service and the Public Investment Corporation.

The economy was Ramaphosa’s main focus, however, and he convened a jobs summit, an international investment conference and a new Mining Charter within his first year.

His framework for a national minimum wage was accepted by Parliament and implemented at the start of 2019. He also pressed ahead with turning the ANC’s Nasrec resolution in favour of “expropriation without compensation” into a series of realistic policy proposals for rural and urban land reform.

Despite this flurry of activity, critics claimed at the end of his first year in office that Ramaphosa’s fine words did not amount to appropriate action.

At the start of 2019, more concrete policy proposals emerged from the Union Buildings, from steps to overhaul the basic education system, to skills development programmes, and faster labour-intensive growth in tourism, agriculture and the ocean economy.

Key steps towards resolving the Eskom crisis were taken.

Ramaphosa also announced the re-establishment of a National Security Council under his chairmanship, and the commissioning of a powerful investigating directorate – resembling the Scorpions, which were dismantled under Zuma – to address the growing plague of corruption.

Ramaphosa’s stabilisation programme had to be undertaken beneath the shadow of national and provincial elections that were scheduled for May 8 2019.

This required a fine balancing act, because the new president had to persuade voters that his efforts to punish Zuma-era looters were genuine, while avoiding an immediate round-up of political adversaries within the ANC that might leave the movement deeply divided in advance of the polls.

Meanwhile, the ANC remains a motor of corruption and political instability. This does not imply that the movement is likely to kick Ramaphosa out before he has completed two full terms as its president.

It is difficult to see how former president Zuma’s cronies can launch a “fightback”. The ANC likes to imagine it has the power to “recall” a state president, but this alleged power is not found in the movement’s constitution.

To be effective, a recall has to be backed by a credible threat to whip ANC MPs to vote against their own president in a no-confidence vote.

Today’s likely successors – Zweli Mkhize, Paul Mashatile and David Mabuza – each suffer from fatal limitations. Health issues aside, we will almost certainly not see a new ANC president until 2027.

The power of a president or prime minister in a parliamentary system is not a post-election injection; it is accumulated over time. It took Thabo Mbeki some years to centralise personal power in an enlarged presidency.

Zuma’s presidency began feebly in 2009. The new ANC leadership insisted that “collective decision making” would be the new norm. Pretty soon, however, Zuma was using party power to control the state, and state power to control the party.

By the time he was evicted in 2018, he had become a danger to democracy. Ramaphosa’s power will grow as he weeds out old-order apparatchiks and accumulates control of the levers of state power and patronage.

During his first state of the nation address, Ramaphosa made this startling claim: “Together, we are going to make history.”

Only time will tell if Ramaphosa can change the country for the better over the longer term. As in many other countries around the world, political institutions are brittle and public debate has become intemperate. Racial grievances are frequently voiced. And the economy is in a far deeper crisis than is generally recognised.

Debate continues to rage about the likely impact Ramaphosa will have on the future of the country he now leads. Supporters of the president claim that his arrival in the Union Buildings represents a turning point for the nation.

Sceptics counter that Ramaphosa is a weak leader who is unable to confront the inexorable forces tearing South Africa apart.

Many social scientists and historians discount the influence of leaders. They prefer “structural” explanations for events that focus on what is likely to happen in the longer term, regardless of the intentions and actions of particular political figures.

FW de Klerk astonished the National Party in February 1990 when he announced the unbanning of opposition parties and the release of Nelson Mandela.

But the economic and political forces driving the National Party to negotiate were so powerful that any other leader would, sooner or later, have taken more or less the same steps.

In most scholars’ eyes, leaders are the vectors of wider historical forces rather than the “makers of history”.

The arrival of Donald Trump in the White House has brought the “question of leadership” back to global prominence. The late historian Eric Hobsbawm once reflected that the US had “probably elected to its presidency ... a greater number of ignorant dumbos than any other republic”.

No matter how feeble the president, however, “the great US ship of state has sailed on as though it made very little difference”.

If the American political system is indeed “foolproof”, as Hobsbawm claimed, this is because every leader is embedded in a strong system of institutional constraints.

Zuma’s tenure, like Trump’s, confirms that it is far easier for a political leader to do harm than to do good, especially in a system in which institutions are vulnerable. Ramaphosa’s political history should give us some cause for hope on this score.

The Constitution he helped to forge in extremely trying circumstances still shapes national political life for the better.

One of Ramaphosa’s ministers observes that “his strength is that he is inclined to be moderate rather than extreme”.

That may, of course, also represent his weakness. He has not yet pushed the limits of his personal power.

His Cabinet reshuffles have been painfully laborious. Zuma’s legacy appointees in the SA Revenue Service and the National Prosecuting Authority remained in place for months despite the president’s legal entitlement to remove them.

South Africa has a parliamentary system of government, and the president has to work within the constraints imposed by Parliament, by the people and by his party.

Even in such a system, however, a president has the authority to steer a nation by virtue of the force of the ideas and values he projects.

Ramaphosa is gifted and empathic when engaging with and understanding diverse constituencies: traditional and modern; Christian and black consciousness; capital and labour.

He favours institutions that allow the holders of divergent interests and values to engage with one another. But he is deeply hesitant to lobby for his own position, still less to impose his own views directly on others.

He is not, so far, at least, a conviction politician, who can define a set of long-range political objectives and then forge a fresh consensus about how they can be attained.

The true contribution of Ramaphosa’s presidency should not be measured in terms of his purging of factional opponents or his success in staging show trials of the agents of state capture.

He can make a very positive difference to the country by rescuing and constructing enduring institutions, and by entrenching effective and impersonal systems of good governance.

A truly great president, however, eventually has to lead from the front, and by personal conviction.

Publications

Publications

Partners

Partners