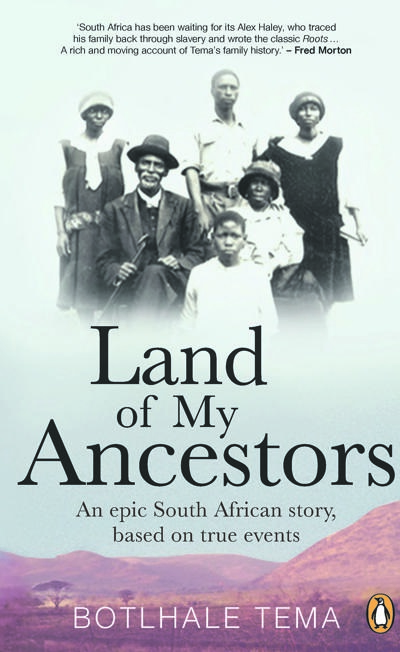

Land of My Ancestors: An epic South African story, based on true events by Botlhale Tema

Penguin Books

269 pages

R189 from takealot.com

First published in 2005, an epic South African book by Botlhale Tema has been republished to highlight the burning issue of land and dispossession in the country.

Growing up on Welgeval, we all knew we were different. Firstly, there was no chief living in our community. Secondly, Welgeval men were dedicated and fierce cattle farmers who called each other “neef” (cousin) and the older people spoke a lot of Afrikaans.

They grew crops such as sweet potatoes and mealies that were different from those grown in neighbouring villages. These crops, together with their cattle, were the means of barter trade with the neighbouring communities. The women looked after children, prepared food, kept homes clean – typical “women’s work” – but they also kept pigs, which were slaughtered mainly in winter, and from the fat they collected, they produced “boereseep” to wash their clothing. These were uncommon activities among black communities in the area. How it all got to be so different, nobody ever offered to explain. In fact, enquiring about these anomalies was an invitation to a smack. Whatever the story was, the old folks sat on it and made sure we never heard it from them.

But the more tightly they kept the lid on our origins, the more curious we children became. As we grew older, we learnt indirectly that not only were we different, but we were also outsiders – we did not originate from within the mountains of Pilane, where Welgeval was ensconced.

Fragments of praise songs that old people recited at weddings hinted at a distant place in the northern Transvaal (today’s Limpopo province) called “ga Moletji” – but no one explained the significance of this.

Welgeval was our home, with a support system for all circumstances and a regular life rhythm in all seasons. This regularity defined people’s roles and lent a sense of belonging. Men ploughed and planted crops in spring; women weeded the fields in summer and did pottery when it was too hot to work in the fields; everybody harvested in winter and prepared produce to barter in neighbouring villages for crops we didn’t produce ourselves. Education was of central importance: all children went to the local primary school before joining their parents in farming or going on to secondary school elsewhere.

As farming on Welgeval grew more stable and successful, ambitious families encouraged their children to enter professions. My father set a non-negotiable rule that we should get a profession before we got married. Parents sometimes sold cattle to pay for their children’s education.

But our habitation of Welgeval came to an end at the height of apartheid. In 1980, it was incorporated into the Pilanesberg National Park, and our people were moved away and resettled elsewhere. We lost a place that had nurtured our family for generations.

Many years later, I stumbled across intriguing information about Welgeval. I was secretary-general of the SA National Commission for Unesco at the time, and one of my responsibilities was to facilitate the implementation of Unesco projects in South Africa. I attended a meeting of the Slave Route project in Cape Town, part of a global initiative to raise consciousness about the history of slavery and to set up economic development projects in the affected communities. At the time, I thought the only slaves in South Africa had been those whom the Dutch East India Company had brought to the Cape. The South African Slave Route project therefore focused mainly on slavery in the Cape.

At the meeting, I exhorted descendants of slaves in the Cape to embrace their history and not to be ashamed of it, arguing that feeling shame amounted to blaming the victims for their history. Later, after I told a historian friend about this, she handed me a book, Slavery in South Africa, to show me that slavery was not confined to the Cape. The book, edited by Elizabeth A Eldredge and Fred Morton, outlines the history of slavery throughout South Africa, including in the Transvaal. It explains how the Boers used to raid villages in the northern Transvaal and bring back “black ivory” in the form of children and women to work on their farms. She pointed me to page 179, where Welgeval was mentioned:

When missionary Henry Gonin arrived in Rustenburg in 1862 for the purpose of establishing a DRC station in the area, he encountered ex-slaves in Rustenburg town and on the surrounding farms. At Welgeval, where Gonin opened his first station, his first enquirers were Dutch-speaking Africans who had grown up in Boer farms and homes. Among them were “Januari”, who worked for Gonin as a servant and interpreter, and was eventually christened “Petrus”, and Vieland, christened “Stephanus” by Gonin. When a boy, Januari was one of the women and children stolen by a large Boer commando during the raid on the BaKwena capital of Dithubaruba, near Molepolole in 1852. Vieland was also captured when young.

I couldn’t believe it. “Welgeval, that’s my home!” I said. “I spent many good years of my youth there and you are telling me I’m a descendant of a slave!”

I couldn’t put down the book that night as I uncovered the most unexpected information about my people. In one of his chapters, Fred Morton says that the history of slavery in the Transvaal was never openly acknowledged, even by most historians, partly because legal slavery was abolished in 1834 by the British, who governed the Cape then, and because the Boer leaders in the Transvaal signed the Sand River Convention of 1852, which agreed to prohibit slavery. This meant that, officially, no slavery was permitted in the Cape after 1834 or in the Transvaal after 1852. However, Morton says that the reality was quite different: as late as the 1870s on the fringes of the Transvaal, slave raids on the Setswana-, Sesotho-, and Nguni-speaking peoples were conducted.

Along the moving horizon of the Great Trek, peoples living in the eastern and northern Cape, Orange Free State and Natal were attacked and seized. Most of the slave raiders were Boers aided by their African allies, and most of the Africans they captured were children. Young captive labourers, often bound to Boer households and raised to adulthood without parents or kin, helped to sustain and consolidate the advancing Dutch frontier.

Another contributor to the book, Jan CA Boeyens, writes that this “new” form of slavery was euphemistically called “apprenticeship” or “inboekstelsel”. The captured children were referred to as “inboekelinge” because their presence in the Transvaal had to be recorded, or as “weeskinders” (orphans), a false explanation of why they were separated from their parents. They were also called “kleingoed” (little ones), “buit” (booty) and “black ivory”, as opposed to the real white ivory that the Boers collected from the northern Transvaal, where they also raided for cattle.

Morton writes that an important characteristic of the inboekelinge was their assimilation of the Dutch culture: they spoke mainly Dutch or Afrikaans, and they were adept at most Dutch household chores (cooking, butter- and soap-making) and economic activities (tannery, carpentry, gun and wagon repair). These were some of the activities practised by my people at Welgeval.

Publications

Publications

Partners

Partners