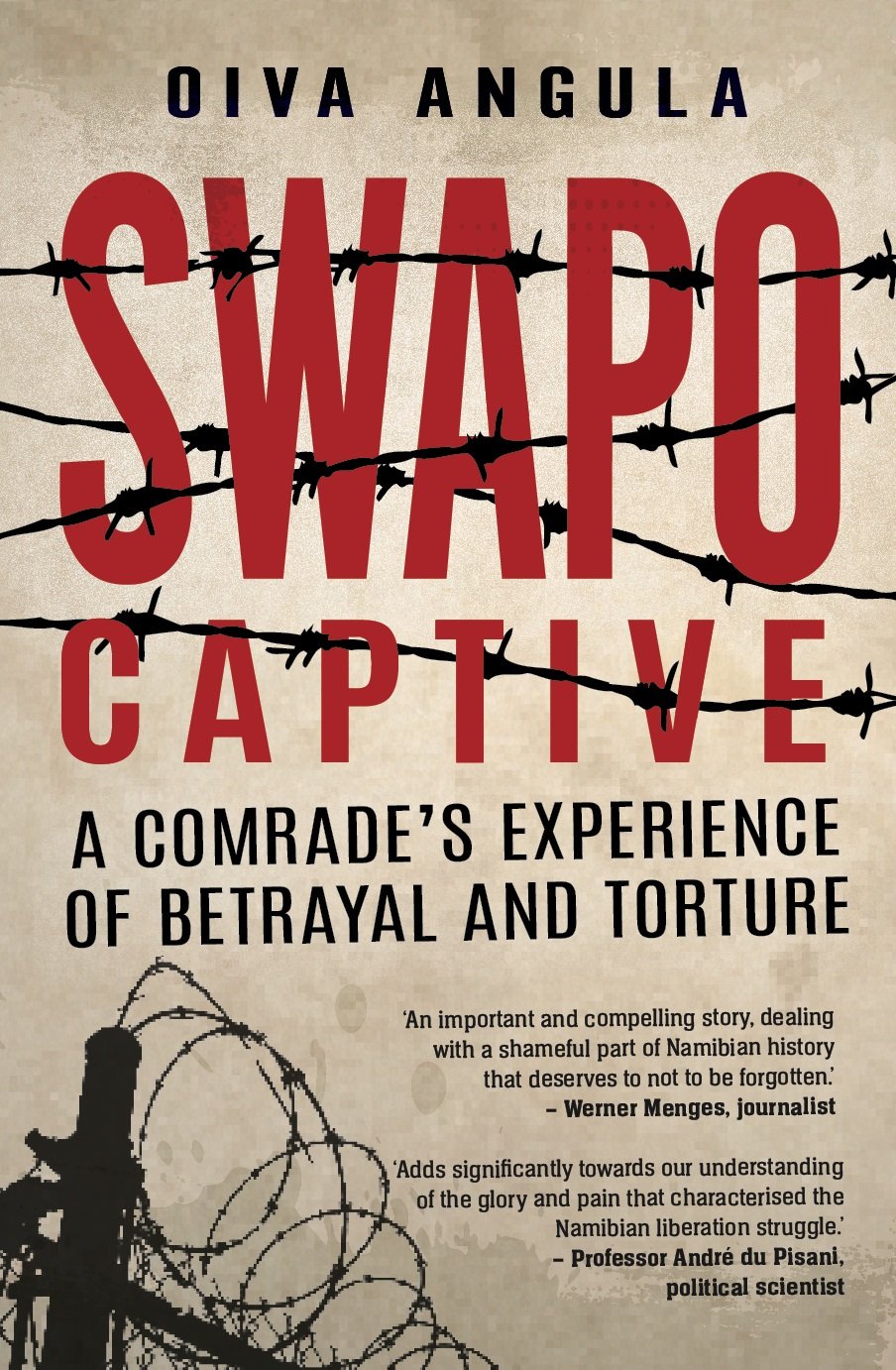

A young Namibian goes into exile to join Swapo’s military wing, Plan, in the late 1970s.

A series of purges within the organisation lead to him being wrongfully branded an apartheid spy and traitor.

So begins Oiva Angula’s terrifying story of betrayal and torture by his comrades, which culminates in imprisonment in the omalambo – the hidden pits in Lubango, Angola, into which he is cast and left to die.

This is an extract from Chapter 3 – A New Journey

After the assassination of Paramount Chief Kapuuo on March 27 1978, a crescendo of dangerous and increasingly dramatic events signalled that it was finally time for me to go into exile.

South Africa’s jackboot of occupation was becoming unbearable.

Political repression was acute. Liberation activists were harassed, put on trial or imprisoned. Mass detentions in the military conflict areas in

the north of the country were common, as was torture of political activists.

The desperation of the colonial regime in the face of increasing anti-colonial resistance explained the intensity of its repressive tactics, massive military build-up, as well as incessant aggression against Angola and Zambia, countries that were providing Swapo with bases outside Namibia.

I was disenchanted with the situation and did not know how to survive the apartheid lash. Many young people were fleeing to join either Swanu or Swapo in exile.

Some left because they were hounded by the colonial authorities and feared for their lives.

But many went into exile gracefully, their flight glorified as an expression of opposition to white colonial occupation. Real freedom was beckoning Namibians, but our shouts of “A luta continua, a vitória é certa!” at rallies were becoming mere platitudes.

One thought buzzed in my head: I have to leave the country and study or train as a guerrilla fighter to dislodge the colonial administration from my native soil.

At first, I confided the idea of exile to my father, who was unimpressed and seemingly worried.

“Son, you should not leave home for exile. Life there is not as rosy as people say,” he cautioned, adding that exile would displace me, both emotionally and physically.

“I advise you to stay and still fight for freedom from here.”

I was defiant and my father was upset.

“I am not opposed to your association with Swapo, but trust my words, son.”

He explained with vehemence why he did not want me to go: “The devil you know is better than the devil you do not know.”

My father had spent about 12 years in exile and knew the wretchedness of life away from home. I thought about abandoning the idea altogether.

But the desire to leave Namibia nagged at me. I bypassed my father and talked the idea over with my mother.

“I want to go to Angola,” I said.

“That is a good idea, son,” she replied without hesitation.

“If we do not struggle, there will be no freedom. I know you will just be like a small fry in a big lake there, but your contribution to the struggle is needed.”

She said that if we want freedom and yet do not fight, we will be like those who want crops without ploughing the ground, or women who want to bear children without experiencing the birth pangs that go with it.

“Have you ever seen good rains without lightning and thunder?” she asked.

“In the past I asked you to go, but you kept on insisting the struggle is here.”

She shamed me on this score, but I replied firmly: “Yes, I wanted to continue with the struggle here, but the situation leaves us with little choice to stay much longer. Kavenamuua and I have decided to leave. Now.”

“Do you want to escape through Botswana or Angola?” she asked without missing a beat.

I clearly remember looking at my silver Citizen watch she had bought me when I was a sophomore at MLH. It was 6.30pm. Mother promised to arrange transport that would take us to Owamboland.

She left for Donkerhoek and returned with a Ford pickup. She packed a few of my belongings in a bag, walked me to the waiting truck and saw me safely into it.

“Go well, son,” she said.

“May the good Lord be with you all the way until we meet again.”

The words were so simple, but so definite. Parting from my family was a serious occasion, especially from Kuku, whom I so loved and adored. Yet I knew my relatives would always be in my heart and thoughts. I looked down at my younger sister’s pale face and into her apprehensive eyes.

“Goodbye,” she gestured at me. I kissed my mother a fond goodbye.

“I love you, son,” she said. “I am going to miss you.”

The journey to Owamboland gave me time to reflect on the unfolding political events in the country and to form a picture of what lay ahead in Angola.

I did not wish to remain any longer under white colonial rule, but the thought of forsaking family, friends and home was overwhelming.

I was leaving behind the only country I had known and the love, smiles and laughter of relatives, friends and comrades – until my return one day, God willing.

It was early morning when the pickup dropped us off at Oluno, near Ondangwa. There were South African soldiers and makakunyas – tribal soldiers who were part of the colonial military – in their Hippos, the large mine-proof troop carriers mounted with machine guns.

The sight of these war machines was terrifying to anyone who knew the situation in Owamboland.

We met Johannes Kambuaimue and his fiancée, Helga Jacobine Kauhanda, and their baby girl, also on their way into exile. Kavenamuua and I slept for two days at the house of Dr Thomas Ihuhua and his wife, Si Jacobine.

I shall remain forever indebted to them for their spirit of magnanimity during those trying times.

On the evening of April 26, a white Anglican Church sister transported us to Odibo.

“If we are stopped at a roadblock, I will tell the soldiers you are patients from hospital. Do not say anything,” she cautioned.

We eventually did encounter a roadblock, but got through without any hurdle. At Odibo, we were put in the care of a family and hidden in a rondavel, a small traditional hut made of wood and grass.

“This is a war area,” said Tate David, the homestead figurehead. “Do you know this area?”

We shook our heads.

“The situation is dangerous and you must take special care,” he told us. “You should not move around. I do not want other villagers to see you in this homestead. One never knows, some of them might alert the army.”

We spent the night there and the next day we stayed inside the homestead. We could hear the distant sounds of army trucks, and the roar of helicopters as these machines of occupation flew over the village.

In the distance, we saw soldiers sweep the bush for Plan combatants. The twenty-minute search felt like it lasted for hours. Luckily, the soldiers did not carry out door-to-door searches of the homesteads this time.

“You can see and hear it for yourselves,” Tate David said.

“If they find you here, they would arrest all of us and possibly torch our kraal. You will be taken across the border when it is dark.”

I became more anxious as the hours dwindled towards dusk. It was a nerve-wracking wait. Then, suddenly, the Plan combatants emerged from the nearby bush. Each of them had an AK-47 rifle with ammunition and at least two hand grenades. They were all young fighters in their twenties and thirties.

As a boy, I had heard stories that Plan fighters were able to disappear in the wink of an eye. I felt pent up with emotion, delighted at the prospect of being a guerrilla fighter and sharing their doughty life. I was part of them now. The beginning of a new life was at hand.

The guerrillas, carrying their AK-47s like fishing rods, ordered us to line up for the long march into Angola. They strongly discouraged us from venturing out of line.

Koevoet (meaning “crowbar”), one of the SADF“s killer squads, was hunting Plan fighters like animals, and in this area you could easily drift into ambushes or step on landmines set by South African soldiers. I was terrified at the thought of it.

Under the cover of darkness, we made our way over the rusting barbed-wire fence that ran along the border between Namibia and Angola, from the Cunene River and the Ruacana Falls in the west to the Kavango River in the east.

The security fence, all 420 kilometres of it, had been put up in 1976 to prevent the influx of armed guerrillas from the north. The fence was now trampled and broken, offering little in the way of resistance to the south-bound forces of change.

We walked the whole night. The moon was low in the heavens. No one spoke, and the only sounds were the rustle of the evening breeze through the trees and the crackling of dry leaves under our feet.

At dawn we reached a homestead, where we were served porridge and meat. After resting a while, we continued our journey into Angola. The route was little more than a jungle track. All traces of civilisation had disappeared.

Thick forest rose on either side of us, and if I had not been so walking-weary I would have rejoiced in the wealth of birdlife that I glimpsed flitting and calling among the trees.

The trip lasted several days and all the time we slept in the open air.

When we arrived at a temporary Plan base, our belongings were searched. My cash, driver’s licence and family photographs were taken with a false promise to be returned later.

I was made to taste my toothpaste and body cream – a Plan commander explained that the South Africans were sending agents with poison to kill Swapo leaders.

In the evening, we were picked up by a military truck, which steered a course across a highland prairie overgrown with grass and shrubs. Tired and hot, we eventually arrived at a Plan base at Oshitumba, known as Socialist Camp.

One of the officers in command of the camp was Patrick Iyambo, whose combat name was Luganda. He was a legendary guerrilla fighter whose courage and tactical skills overpowered the enemy on the battlefield.

The reception was genial and warm, but although we spoke the same language, the people acted differently.

My journey had called me out into a jungle wilderness. I searched my heart; in the still quiet of these moments, time stopped.

I suddenly felt alone and aware of being in a strange and distant land disconnected from anyone and anything familiar.

Publications

Publications

Partners

Partners