The Longest March by Fred Khumalo

Umuzi Publishers, an imprint of Penguin Random House

264 pages

R230

Historical fiction is a genre that has gained a lot of popularity over the past few years all over the world. It is difficult to account for such an occurrence except to say that, for a number of writers, it has seemed important to look into the past in order to understand what the contemporary world is like. This should not be a surprise because, as many people opine, it is extremely difficult to comprehend the ways in which events are unfolding in the present, and a glare into the past, some suggest, is perhaps the best way to understand the contemporary period.

When I received Fred Khumalo’s latest novel, The Longest March, I was quite surprised, reading the back cover, that his follow-up novel would also be a historical one. This is because just two years ago I had reviewed Khumalo’s impressive novel, Dancing the Death Drill, and I was taken by this author’s ability to look at a largely forgotten historical event and bring it to life for readers in the 21st century. In reading what The Longest March was about, I found that it would be another reckoning with the past. This time Khumalo looks at the 1899 Zulu march that took place from Johannesburg to Natal right before the onset of the Anglo-Boer War.

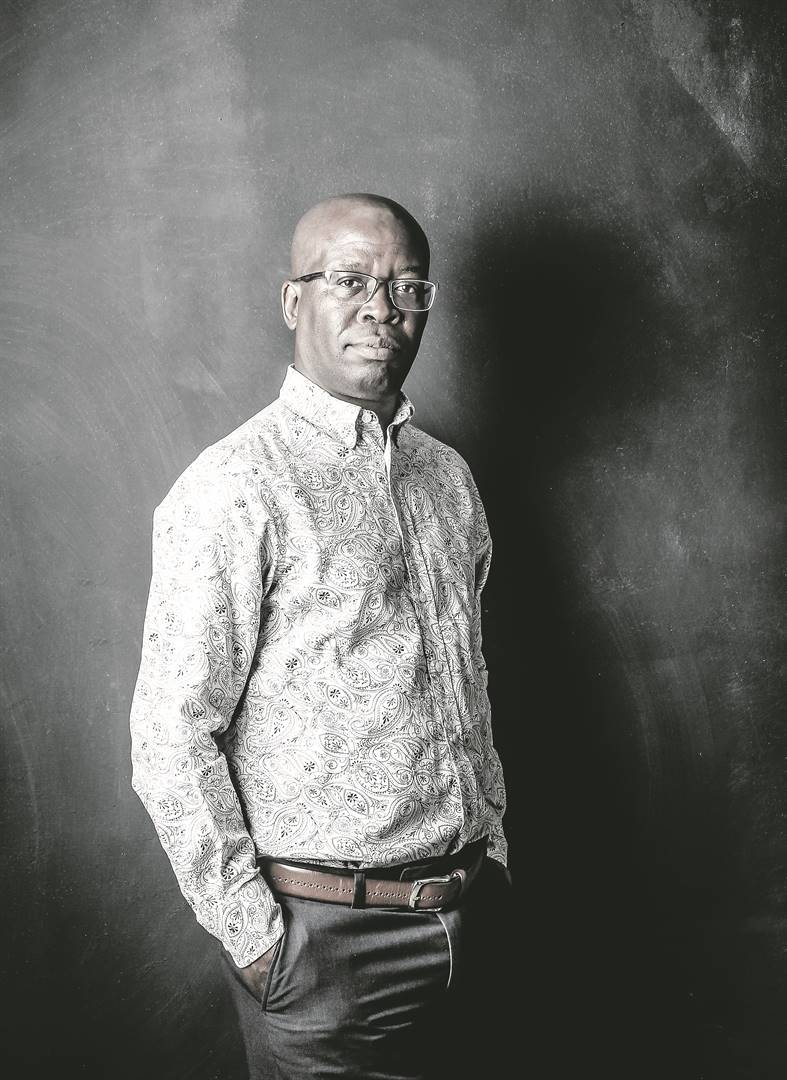

When I meet up with Khumalo at his home and ask how the idea of this novel came about, he says that “I was driving, listening to 702, the Jenny Crwys-Williams show, and she was interviewing a documentary director about their film relating to this incident I wasn’t aware of. I’d never encountered that story before so I listened attentively”, and it was from this that the seeds of the novel would be planted. Khumalo then engaged in further research, trying to understand a march that was undertaken by 7 000 mineworkers, and he says that he did not want to write a story that would merely be about facts and that is why the fictional form was attractive to him. “I needed to understand the characters,” he says, “what drives them? That’s when I started creating my characters.”

The Longest March is a novel with three central characters – Nduku, Philippa and Xhawulengweni – and it takes place in 1899 in southern Africa. The story is told from each of these character’s perspectives, as we get a glimpse into their individual histories and what led to their being in Johannesburg in the late 19th century. The novel starts a few months before the march that was a consequence of a looming war.

The Johannesburg in the novel had only existed for a few years and could not have been conceived as the place that it is today, although early signs were already there. The story tells that “born just less than 20 years earlier, Johannesburg is still not a place for children. It is still too young to have a family-raising culture.” Most of the black people who are in this Johannesburg are miners, there to seek work and escape their places of birth. The three main characters have all left their places of birth and a common theme that runs through their stories is a sense of oppression that they felt where they lived.

In many ways then, this is as much a story about the past as it is about the present. In the Johannesburg of 2019, there are still thousands of people who arrive from all over the world, attempting to create new lives in this city. Johannesburg, in other words, continues to retain its foundational aspirational values. It is a place, for many, where biographies can be rewritten.

This city is, however, called to a halt when a war approaches and the central characters find themselves having to participate in a march. One of the characters who plays an important role in the organising of the march is Nduku. He helps his “boss” Marwick organise the march and, because Marwick, who is also known as Muhle, is white, he is able to arrange with the colonial government to allow the marchers to walk back to their homes. Nduku, on the other hand, is tasked with the responsibility of speaking to the men in the mines and convincing them to join the march. Signs of a deteriorating city were already visible as job and food shortages were becoming evident.

Nduku at first resents having to march and having to take on the responsibility of organising it. He tells his partner, Philippa, that he does not want to lead the march: “Who said I wanted to be a hero? Who said I wanted to save lives? I came to Johannesburg on my own. And I intend leaving on my own.” The reasons for Nduku’s reluctance to take on a leadership role become evident to the reader later. One of the things we learn is that, as a young boy, he lived under King Cetshwayo’s rule, as his father was a herbalist for the ruler. Nduku was himself being groomed for leadership before other events disturbed this journey. He would find himself at a mission school and then, with disruption once again, he came to be at the mines.

Philippa, however, urges him to join the march. She tells him, “Fate is offering you yet another stab at redemption: stick with this white man. Be part of his plan. I’ll be with you through it all” and tells him that “We have to face the truth, Nduku – you’re afraid of commitment.” It is from Philippa’s words, mostly, that Nduku is convinced to join the march.

His and Philippa’s story is a tale that is deeply troubled. The two met accidentally in Kimberley when Nduku found a place to have his suit fixed, and she worked there. Philippa – a white woman – “had never encountered a black man who wore a suit and spoke English with such ease”. It is from this encounter that a romantic relationship would develop.

It turns out, however, that Philippa is in fact not “white” but has passed for the identity as a coloured person. Philippa is one of the many coloured people who were able to pass for white because of how they looked, even though her mother is black and her father coloured. When I ask Khumalo where the idea for this character came from he says that he has a cousin who passed for white during apartheid and that he was interested in exploring the social and psychological effects of this. Speaking about his cousin, he says that “we talk about this and she says she had to do it in order to survive … I could identify with my cousin completely because at that time you had to work with what you had. You take advantage of what the system gives to you.”

The most interesting character, for this reader, is Xhawulengweni. He at first appears as a big-bodied strong man who can achieve anything until this expectation is thwarted. One of the biggest stories of the 19th century in southern Africa revolved around the gang leader, Nongoloza, “who was soon to emerge as the “original modern criminal in South Africa”. Khumalo uses this historical figure and attaches him to his own characters. Xhawulengweni is one of the men who has been under Nongoloza’s tutelage and has consequently “sharpened his pickpocketing skills”.

When the idea of the march from Johannesburg is proposed, Xhawulengweni sees it as an opportunity for him and his gang to make money by pickpocketing the people who would be in the march. However, it turns out that Xhawulengweni’s reasons for wanting to participate in the march are much more sinister, if not sadder, than one would assume. Xhawulengweni has a past romantic relationship with Nduku and part of the reason he participates in the march is to try to win him back.

When he engages with Nduku about this prospect of rekindling their love, it is evident that Nduku is no longer there. He tells Xhawulengweni, “You’re like my brother. I respect you, and always will. But what we had ended a long time ago. I thought you’d made peace with that.” Xhawulengweni responds by saying, “I’ll love you more than that white bitch of yours does and you know that” and much of the novel, as the march starts from Johannesburg, is driven by this love triangle.

When I ask Khumalo why he took homosexuality so far back in southern African history, he says; “I wanted to dispel the notion that homosexuality is a white person’s thing. No, it has always been there. It’s just that it was hidden. People didn’t want to come out because they would be ostracised, beaten or killed.”

And when I ask about the love triangle he has created he says; “We are more used as a society to heterosexual love triangles. I was trying to imagine what it would be like having two guys who are in love and the woman comes in and breaks the affair between them.” This is precisely what Philippa does, and the consequences that emanate from this I will leave for the reader to find out.

Khumalo is a prolific author who has written books that look quite deeply, and comically, at South Africa’s past and present. What stands out about this author is his ability to be comfortable and immensely successful in writing both non-fiction and fiction. His fictional books include Bitches’ Brew, Seven Steps to Heaven, Dancing the Death Drill and a collection of short stories. He has written a very successful autobiography titled Touch my blood, and is an accomplished columnist. When I ask him why it is that his fiction is always looking at the past he says, “I feel our history as black South Africans hasn’t really been told, especially from our perspective.”

Speaking about Bitches’ Brew, Khumalo says, “What I sought to do is to show that, in as much as apartheid overshadowed everything, we still lived simple lives as black people. We still made love and made music, despite apartheid.” He therefore sees his task as a writer as giving life to those who have been excluded by the historical record. Indeed, in reading about the events of the 1899 march, he says there are hardly any black people who are credited with the march. It is a history, similar to the recent history of the world, that continues to centre white people and this was something he wanted to challenge. He sees his task, he says, as a “political intervention” which is meant to expose “South Africans to a hidden pocket of our history”. Through this he is “hoping to celebrate our humanity as South Africans; where we have been and what the past did to us”.

Before I end my interview with Khumalo I ask him about a similar 10-day march that he is about to undergo, retracing the very journey he has written about from Johannesburg to Natal. On why he would put himself through such a strenuous challenge he says, “I’m trying to bring attention to the march; to test my endurance as a human being. It’s a journey within myself that I don’t want to talk about now. I want to challenge myself and to see what happens. It’s going to be the longest march to finding myself.”

Nthunya is a PhD candidate in literature at Wits University. He studied literature, history and philosophy at Rhodes University

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Get in touchCity Press | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Rise above the clutter | Choose your news | City Press in your inbox | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| City Press is an agenda-setting South African news brand that publishes across platforms. Its flagship print edition is distributed on a Sunday. |

Publications

Publications

Partners

Partners