Johannesburg: ‘Becher’s Brook, Second Time Round’ April Fool’s Day 1947

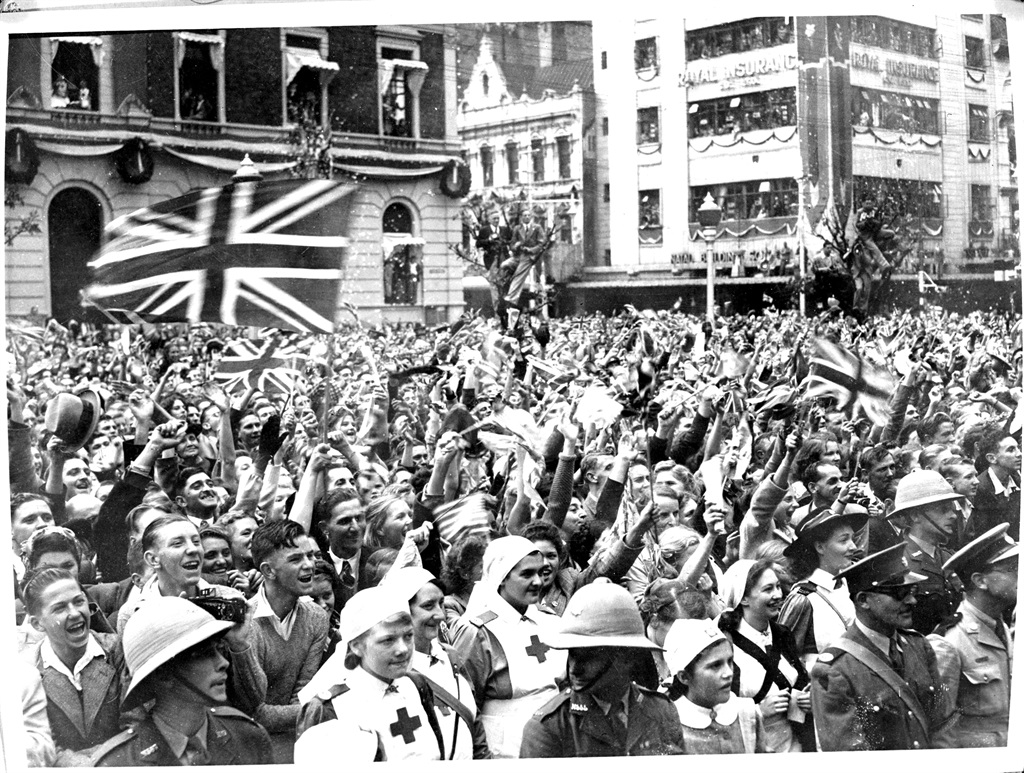

All over Johannesburg, in the weeks leading up to the visit, a great sea of Union Jacks (and some of the St Andrew’s Cross to honour the Queen) had been raised. Many were over public buildings and skyscrapers, where they were flown jointly with the South African flag, giving the impression from a distance of the “many-turreted castle” that The Star said the city’s skyline now presented to welcome the Royal Family.

Many more were raised over private homes, in both richer and more modest suburbs. Fluttering in the Highveld breezes, they made an impressive sight, and symbolised a shared social and political identity. For many families, keen to follow the example of their Anglo-Saxon neighbours, this was a first, and one or two journalists felt obliged to point out, drily, that some of the Union Jacks were being flown upside down.

There was also in Johannesburg a large poor white Afrikaner population, mostly living to the south of the city centre and in some of the less salubrious areas along the Rand, whose lives were – unintentionally – becoming more English, though certainly not in politics or sentiment. (The same could be said for many Afrikaners of that era.) Not many flags were raised in these areas; none of them were Union Jacks. Urbanisation had not been easy for these people.

One of the many Nationalist grievances was that the business world was almost exclusively in the hands of the English-speakers and the Jews. As late as 1937, Die Transvaler estimated that there were only 20 Afrikaans enterprises in Johannesburg.

Significantly, English surnames predominate in the long guest lists for Johannesburg’s Administrator’s Banquet, the two civic lunches and the Princesses’ ball. There is a fair smattering of Afrikaans names, no more, and some presumably belonged to people who had anglicised. The names of prominent Jewish families appear too. The leading Johannesburg baronet and knight, Sir George Albu and Sir Ernest Oppenheimer, respectively, and their wives, whose names both appear just under the titled courtiers and civic officials, were both of Jewish descent, though by this date practising Christians.

The weather, until then at any rate, had remained glorious, with all the snap and sparkle of a Highveld autumn morning, and the finest air in the world – the much-vaunted “champagne air of the Highveld” (as the newspapers and travel agents were still able to claim) – swept up to meet them as the open tourer drove steadily onwards and upwards along the madeup dual carriageway. Finally the procession passed under the triumphal arch that marked the then boundary of the greater city (near Bramley); the route led on through some of the suburbs which by that time were spreading rapidly north, east and west of the city and boasted names like Orange Grove, Yeoville, Dunkeld, Rosebank, Houghton and Parktown, all essentially conforming to the English garden suburb prototype on the lines originally envisaged by Ebenezer Howard.

This replicated further the very English ideal of rus in urbe, which had been introduced to the Cape in the early nineteenth century and remained the pervasive vogue in urban South Africa. At this date, there was more than a hint of WASP California thrown into the mix too. Here, jacaranda’d avenues were lined with comfortable houses of mostly unremarkable architectural merit, set in intensely gardened plots that benefited from a marvellously repaying horticultural climate, and often boasting a tennis court and, increasingly, a swimming pool.

By now the crowds on the pavements were thick and continuous, and augmented here and there by phalanxes of schoolchildren in their uniforms: the boys of King Edward VII School, the girls of St Andrew’s and Roedean. The King Edward’s boys had strung a welcoming banner across the road and gave the school war cry (“Gigamalayo Gee! Gigamalayo Gee! Teddy Bears, Wha! Who are we: Teddy Bears!”) as the Daimler passed. Marist Brothers and their band were stationed on the crest of Orange Grove Hill; nearer the city, the boys of St John’s College lined the road. Among the spectators, too, standing side by side with their employers, were many domestic workers (uniformed too, but quite differently, of course) and given the morning “off”; many responded to the cavalcade with waves, ululations and cries of “Hau!”

By 9.50 the Daimler had reached Clarendon Circle, the elegant circus that was considered the entrance to the city proper. On this day it boasted a mammoth crown at its centre, designed by the architectural branch of the City Engineering Department and installed by the Parks and Estates Department; its outer circumference was ringed by the helmeted city constabulary, standing smartly to attention in uniforms identical to those of London bobbies.

The Jeppe Boys’ High Pipe Band and the St John’s Ambulance Brigade Boys’ Band were stationed to play at the Circle; the King saluted as he passed and the crowd of 6 000 (the northwest side of the Circle being “lined with natives”, as The Star reported) cheered wildly. At this point, the colour scheme of the civic decorations, which had been a patriotic red, white and blue since the Bramley arch seven miles (11 kilometres) back, changed abruptly to green and gold, the colours of the city. By then, the full extent of Johannesburg’s incredible reception must have begun to dawn upon the Royal Family and the Household. One million people in all were there to cheer the Royal Family that day; this would prove to be the greatest South African welcome of them all.

Publications

Publications

Partners

Partners