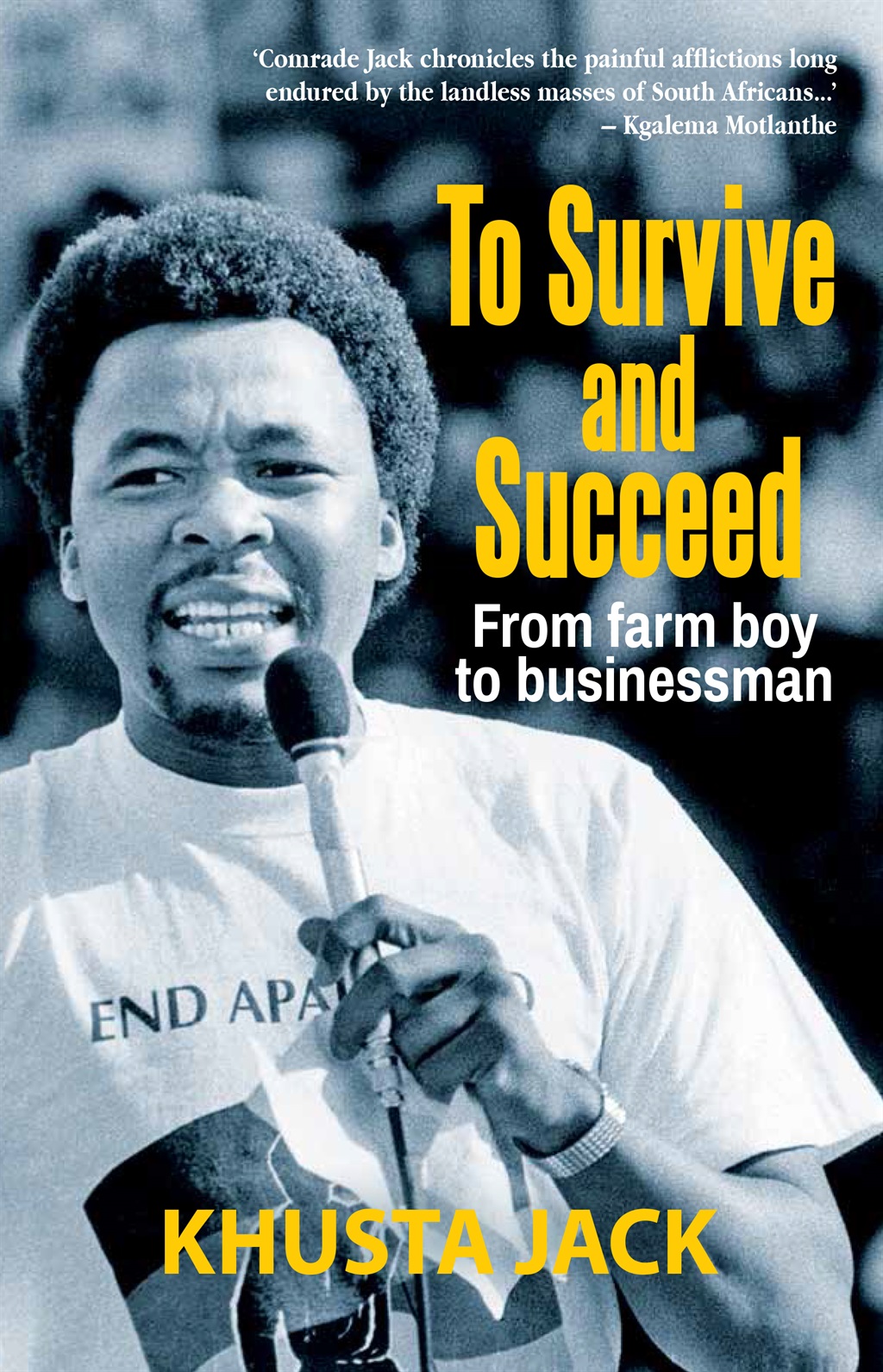

In this extract from the book To Survive and Succeed by anti-apartheid activist Khusta Jack, he recalls how his family had to leave the farm where they lived because the white owner of the farm wanted them gone.

Without a trace

At the time of my birth not a single person in my home had attended formal schooling. Those who tried it out later didn’t keep it up for long.

There was no school close to where we lived – at least, not one we black children could attend.

The closest school was the prestigious and exclusively white private school Woodridge, off the N2 road that links Cape Town and Port Elizabeth.

The school that admitted the children of farm labourers was at Mondplaas, about four kilometres from our home on the Jeffreys Bay side of the Gamtoos.

The Mondplaas area was controlled by conservative white Afrikaner farmers who dominated the dairy industry in the Gamtoos River valley.

Other farmers were large-scale producers of vegetables and first-grade citrus.

The mud school at Mondplaas was built on the land of a certain baas Dempers Meyer, who later became a member of parliament for the National Party.

For my brothers and sisters of schoolgoing age, trudging sixteen kilometres a day to and from school became too much, especially on top of the chores they had to perform when they got home and many of these tasks also had to be performed in the early morning before school.

Besides, in our small community schooling was not viewed as progress but rather as a form of Christian indoctrination.

The church and school were seen as two sides of the same coin – both brainwashing tools with the aim of undermining our customs and traditional African way of life.

All the stories we were told at home before bedtime were about our own people, stories that emphasised the strength, courage and the importance of our Xhosa ancestors.

Poems of our glorious past were recited, giving expression to both good and sad times in our long history.

We were amaqaba, meaning that we were neither educated nor Christian converts, and none of us was given a so-called Christian name at birth.

My oldest brother and sister never even tried to go to a proper school, but there was a young man on the farm who started teaching them, and other children, to read and write – until his family was forced to move and look for a place on another farm.

The only evidence that my brother could write is the tattoo on my left arm which says “Elvis Presley”.

He used a needle to break my skin and then rubbed in a black substance from a battery, possibly lead dioxide.

I was six years old at the time. Elvis clearly had a strong impact on my brother, though I can’t imagine how he came to know about the “king of rock ’n roll”: where we lived, there were no newspapers or radios, and definitely no television.

One day around evening milking time, not long after I got my tattoo, my mother returned from working in the fields as usual.

But from the expression on her face I could see that something was wrong. She looked shocked and upset. I’d never seen her like that before.

We children crowded round her, wide-eyed, as she told us we had to pack up everything and be gone by sunset the next day.

Talking fast in her panicked state, she told my older brothers to go to families on neighbouring farms to ask for help: to see if they could take care of a few cows or goats for us because the farmer, Koos van der Walt, had told her we must leave nothing behind; there was to be no trace of us.

When the men came back from milking they were talking about the farmer’s orders and shaking their heads.

Men and boys, and some women too, came to help. The adults started sorting and packing up.

Everyone was grumpy and touchy. I kept asking why we were leaving, and whether we were going to come back, but the adults brushed me aside, too busy to bother with my questions.

Eventually I was told the white man was the owner of the farm and he wanted us gone.

Until then, I had thought that where we lived and where my mother worked in the fields was our land. It was the beginning and end of my world.

I had no idea that there was a white owner – a boss of our lives.

One of my brothers walked over to Mondplaas to give the terrible news to our Uncle Oudenks, one of my Grandpa Kholisile’s sons.

He said we could come and stay with him and then dispatched his own sons to find out from other families what help they could offer.

The next day support came in small welcome measures. Local people offered help in all sorts of ways.

Some offered to hide us from their own employers who would definitely have objected to having “more blacks on their land”.

Some took care of our livestock – taking four or six goats each – keeping the numbers small to avoid detection or suspicion from their mlungus (white bosses).

There was much coming and going the whole day with everyone kept frantically busy. I simply felt helpless and confused.

Publications

Publications

Partners

Partners