US scholar Reynaldo Anderson is the co-editor of a collection of academic essays called Afrofuturism 2.0: The Rise of Astro-Blackness. He recently joined forces with local writer Bongani Madondo in a colloquium and a series of workshops on black sci-fi in Joburg. Grethe Kemp asks him about Afropessimism, the film Black Panther and Afrofuturism 2.0.

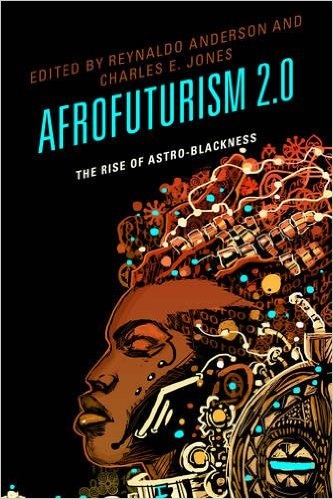

Academia around the idea of Afrofuturism – the intersection of black identity with technology – has existed for many years, and the term has gained traction with the explosion of black-centric films like Black Panther. Reynaldo Anderson and Charles E Jones’ 240-page book Afrofuturism 2.0: The Rise of Astro-Blackness places the term in the school of Africana, and uses it as a lens to look at subjects not previously tackled, including religion, architecture, communications, visual art and philosophy. The book has already been praised by academics and writers, with literary journal The Skinny Poetry Journal calling it “a significant literary achievement” and “scholarship [that] is absolutely astounding – a work of passion, creativity and excellence”.

Anderson is currently on something of a world tour promoting the book, and #Trending caught up with him via email to ask him more.

You were involved in a colloquium on the book two weeks ago with Bongani Madondo. So how did you end up in South Africa?

I was introduced to Bongani Madondo through graduate student Michelle Mlati. Michelle was using my co-edited book Afrofuturism 2.0: The Rise of Astro-Blackness in her scholarship, and I saw her post on Instagram noting how important the book was to her work. Michelle and I corresponded and discussed the possibility of collaborating on an event in Johannesburg with the Black Speculative Arts Movement and South African Afrofuturism enthusiasts. Michelle indicated her schedule would prevent her from organising the event on her end and she connected me with Bongani. Without the insight and organisational ability of Bongani, the event would not have been possible.

What is your definition of Afrofuturism?

Afrofuturism 2.0 is an emerging Pan-African transnational, trans-contextual, technocultural social philosophy characterised by other dimensions that include African or African diasporic metaphysics, aesthetics, social sciences (such as Afrocentricity, Black/African feminist and womanist thought, or Black queer practice), theoretical and applied science, and programmatic spaces.

For our readers, why do we call it Afrofuturism and not just sci-fi?

What we now call Afrofuturism (or the Black speculative tradition) and the largely white male Eurocentric science fiction tradition developed during the genesis of the industrial revolution, global slave trade and emergence of modern science.

However, Black speculative thought was conceived in the 19th century and early 20th by diasporic African writers and leaders such as Martin Delany, Pauline Hopkins and WEB Du Bois. The Black speculative tradition is a response to the Western transatlantic and Arab slave trade, scientific racism and white supremacist global hegemony as a utopian antidote in pursuit of freedom; the emergence of Western science fiction develops as a reaction to the European enlightenment project focused on progress.

Moreover, both traditions were largely shunned by the intellectual mainstream literati until after World War 2 and the growth of the modern media industry, African and/or Black artistic/liberation movements, and the development of scientific projects like cybernetics by Norbert Wiener.

Why Afrofuturism 2.0 – what came before?

The previous iteration of Afrofuturism was an African-American-centric post-Cold War framework based on the notion of a digital divide and the growth of the popular use of the internet by the mid-1990s. However, the contemporary second wave of Afrofuturism is a global 21st-century Pan-African response to the growth of social media platforms and digital technologies. Furthermore, new media technology has compressed the space-time awareness of Africa and its diaspora with regard to developments like the incorporation of the African diaspora as the sixth zone of the African Union, the 2008 collapse of the Washington Consensus on global finance, a post-American world order, global migration or climate change, and the rising tide of fascism and authoritarianism.

I also want to note that it is not unusual for the African diaspora and continental Africa to exchange political or cultural ideas across the Atlantic. To be more specific, the South African freedom struggle educated the African diaspora on the connection between global capital, the land question, foreign policy and the power of young people.

What did the colloquium and workshops entail? What were some of the most interesting points that came up?

The WiSER symposium was organised around concepts such as artificial intelligence and the fourth industrial revolution, grass roots activism, African art, global capital and indigenous healing systems. The members of the Black Speculative Arts Movement came to learn from our African counterparts and we learnt a lot. For example, the knowledge of Zulumathabo Zulu in the area of indigenous metaphysics and science, and the connection to contemporary practice was excellent. The wisdom of Dr Nokuzola Mndende and other practitioners on the panel of indigenous healing systems in her/their discussion of African traditional religion, divination, psychology and its suppression by the modern state was inspiring and informative. The intellectual rigour of lecturer Raimi Gbadamosi across several dimensions of African and African diaspora scholarship was outstanding.

However, the most powerful presentation, in my opinion, was given by the young activist women on the grassroots panel focused on the intersection of social media with the rights of women, the poor and the landless of South Africa. For me, they really drove home how rape culture, capitalism, technology, organising across gender and class lines, and the suspension of male privilege can be successful.

Bongani mentioned to us that Afrofuturism had its own San, Xhosa, Zulu, etcetera magic-realist and astro-expressions. That’s very interesting. What are some examples of this?

I think Bongani is more qualified to talk about this perspective than me. However, during my time there listening to Zulumathabo Zulu, I can see how the cosmic knowledge system of the Basotho as explained by him lends itself to incorporating theoretical, empirical, metaphysical indigenous approaches as a framework for African futuristic tradition, or perspective, on contemporary Afrofuturism.

You say your stance is to acknowledge that Afrofuturism has a strong ancient and undeniable base. Why has this been overlooked for so long? Why do people think Afrofuturism is a new thing?

The Black or African speculative tradition has been overlooked and understudied due to factors such as colonialism, enslavement, Western thievery, capitalist misuse and appropriation, destruction of African schools of thought, and mental colonisation of people of African descent. The practice of Black/African speculative thought and practice has survived under ground and is witnessing a renaissance due to the declining spiritual and intellectual influence of the West and the desire for people to seek other alternatives.

Let’s talk Black Panther. It’s been huge in bringing the idea of Afrofuturism to the mainstream. Is it a good or bad thing that an American movie has had such a big impact on the visibility of African sci-fi?

Largely, it is a positive thing. The movie demonstrated there is a global market for Black science fiction, which will fuel a desire to hire artists who are African writers and producers of the content to develop and create these projects.

I’ve become interested in the literary genre of Afropessimism. In South Africa, I’d define this as writing usually from the perspective of a youth suffering major feelings of disenchantment in a post-democratic era. Would you say Afrofuturism is the opposite of that? Is Afrofuturism always a positive outlook on what the future holds, or not necessarily?

I would argue that Afropessimism, as a critical approach, helps keep contemporary Afrofuturism’s thought and practice, ontologically or its sense of being, firmly grounded, with its sometimes utopian practices, and accountable to the masses of people previously determined by others to be savage or half human and non-human. For many Afrofuturist thinkers and practitioners, the apocalypse, maafa, or disaster has already happened. Afrofuturists are attempting to develop a framework to interpret, re-engage, build or negotiate an alternative future for African peoples everywhere facing intersecting problems of climate change, the rise of artificial intelligence, post-capitalism, recolonisation, and species extinction.

- Afrofuturism 2.0: The Rise of Astro-Blackness is available at takealot.com for R979

Publications

Publications

Partners

Partners