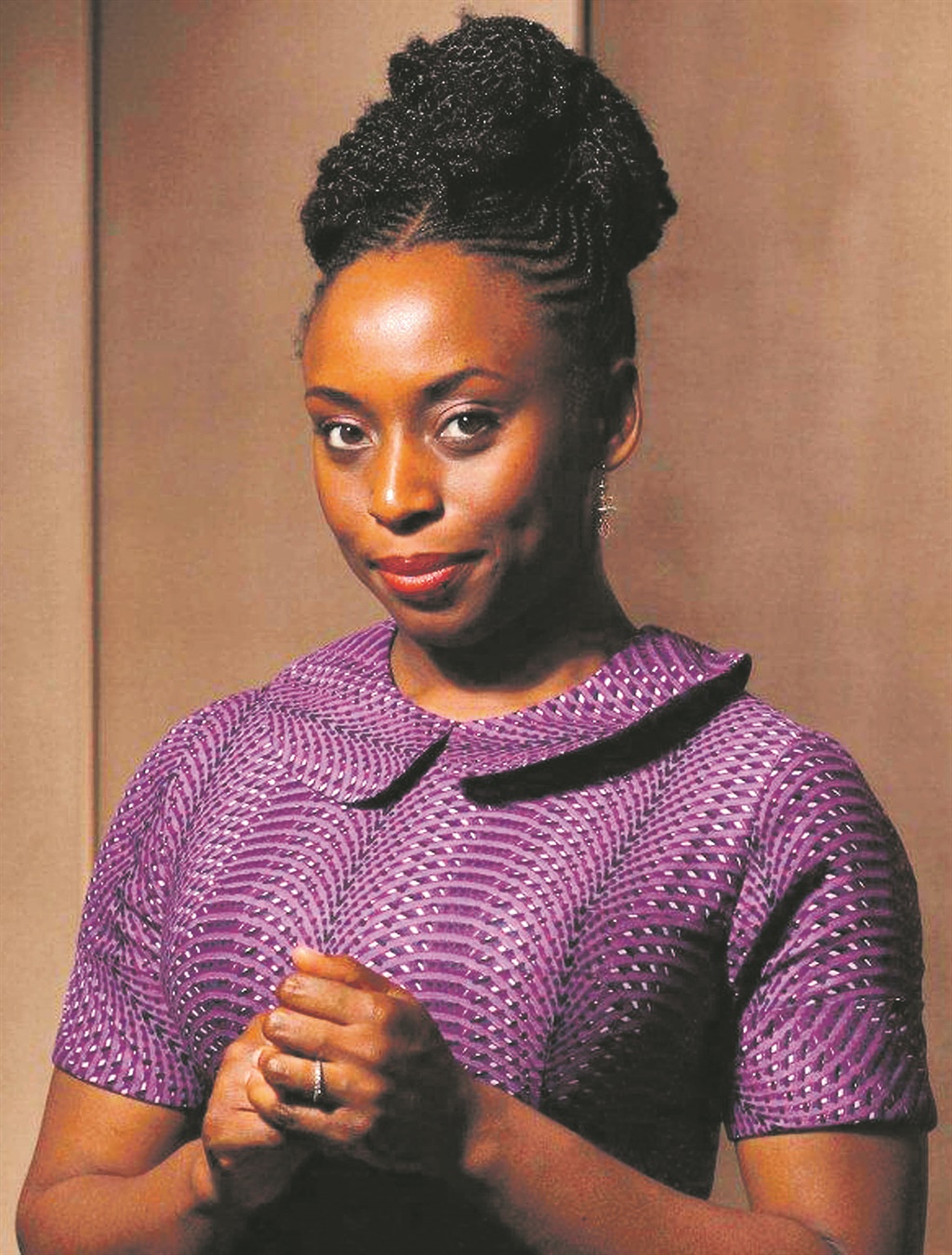

It’s easy to either get caught up in the black girl magic of Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie’s powers, or to join the outrage machine over her views on Beyoncé, trans women and postcolonial studies. Manosa Nthunya believes the key to understanding her views lies in her novels.

Over the past few years, there’s been a bit of a backlash against one of Africa’s most celebrated and bestselling authors, Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie.

This backlash is informed by what many see as callous statements against transgender people when she said: “It’s difficult for me to accept that then we can equate your experience [trans women] with the experience of a woman who has lived from the beginning as a woman and who has not been accorded those privileges that men are.”

Then there’s her opposition to what she sees as Beyoncé’s strand of feminism that is centred on men: “Her type of feminism is not mine,” she said. “It is the kind that ... gives quite a lot of space to the necessity of men.” And then there’s her view that postcolonial theory is the invention of bored academics (such as myself, I guess) who need jobs.

It’s easy to see how some of these views can be perceived as short-sighted, particularly when Adichie has been at the forefront of challenging us to be critical of the ways in which our social positions inform what we are able to see.

The danger of a single story

One of Adichie’s most watched and revered talks is The Danger of a Single Story, where she urges us to adopt a humble disposition and appreciate other people’s complexity. She calls on us to accept the limits of what we know, as we are all shaped by the societies we’re born into. What, then, does a reader who admires Adichie do when confronted by what might seem like a contradiction between her writing and some of her personal views?

Whether one agrees or disagrees with Adichie’s public thoughts is not a matter to be underestimated. But equally important are the lessons that feminism has taught us about society’s relation to women.

Feminists have long argued that women, unlike men, have throughout history been expected to occupy a position that expects them to be pure and clean, and without complexity.

This has been the burden of women as our relation to them (and perhaps sometimes to themselves?) has been catastrophic because it’s still deeply informed by a binaristic logic, where we are expected to either love or hate them. And so it applies to Adichie. Do we now like or dislike her based on what may be perceived as certain clumsy utterances, or do we also read her as someone who has the right to articulate her perspectives and perhaps, at times, also change her views on things? Perhaps the best way to approach this is to look at her work and what it tells us about the human condition.

Kambili

Part of the reason we read is to expand our views on the world and its people. We do this because the world, and its people, is often too complex to understand. If we cannot find answers to this difficulty in our everyday experiences, the promise of art is to offer a plausible representation of life that might undo this anxiety through comprehension.

But much literary fiction tends not to offer the inquisitor the respite needed. What it often confirms and communicates instead is the very obscurity that makes the world what it is. Adichie’s fiction, often set in postcolonial Nigeria, attends to this and the impact of social constructs on those who are marginalised. This is evident from her very first novel.

In Purple Hibiscus (2003), Adichie shows the troubling consequences of religion, patriarchy, a violent state and gender. Kambili Achike is a 15-year-old girl living in a deeply patriarchal home. Her father, Eugene, is a staunch Catholic with very disparaging views on other religious beliefs. More than this, though, he’s an abusive husband who refuses to listen to any voice that disagrees with him.

The repercussions are a violent family structure that leaves its members traumatised. Kambili longs for freedom, but must learn that the price of freedom is always heavy as it can’t be untangled from one’s history.

In interviews, Adichie often says that part of the reason she writes is to shed light on the lives of those denied their humanity by history. This is an ethical act as the writer accepts that the way in which they see the world has been shaped by social norms, and that it is important to make use of one’s imagination to expand on what one knows and on the possibilities that might inhere.

It’s something that can also be seen in Adichie’s contemporaries such as Helon Habila, Ayobami Adebayo, Sefi Atta and Adaobi Tricia Nwaubani, who, in writing about Nigeria, are able to look at the intimate and private lives of their characters to show how these are entangled with larger political and economic structures.

Ugwu

Adichie’s expansive moral imagination comes through in what I suspect will be regarded as her classic work, Half of a Yellow Sun (2006). Here, she takes on the Biafran War of 1967 to 1970 that continues to haunt Nigeria. The novel depicts how the gruesome consequences of war challenge the assumptions that Nigerian citizens had about themselves in how they suddenly turned against each other.

This is much more than a war novel, though. One of the outstanding characters is Ugwu, who moves from a village to work as a houseboy for the relatively affluent Odenigbo and Olanna. Ugwu arrives in Nsukka with a keen interest in learning and pleasing his masters. He aspires to be part of the dominant class even as his existence and how he sees himself are a consequence of the very same socioeconomic structure that he aspires to.

Through Ugwu, Adichie asks pertinent questions: Will freedom for the marginalised only come through access to education and, if so, is access to education not inherently exclusionary? What does it mean to aspire to be like the master? Is freedom, in fact, not only possible if we devalue the very structures that make it possible to create societies where there are masters and servants?

Ifemelu

In her most recent novel, Americanah (2013), Adichie further raises questions about how race and gender intersect to dehumanise the lives of black women. The feisty Ifemelu moves from Nigeria to the US and, for the first time, has to confront how her body has been racialised. She meets people who stereotype and reduce her to what they think they know about black people.

The consequences are shattering as she attempts to

create a home where the possibilities of such a creation

are already prohibited. Ifemelu only attains some sense

of freedom when she starts blogging about how white America sees black people, hair and colourism, and dating white men ...

Adichie here seems to follow a strong feminist trope that argues for the importance of women having a voice in the public sphere.

We are all shaped by history

Adichie’s novels shed light on characters who are born into social and political positions that they do not choose. It is nevertheless these very positions that they have to navigate the world with. These positionings have been the cause of much catastrophe in recent history because the perverse impulse to read the other through a racialised, gendered, tribal or classist lens still lives with us and structures our relations to others.

But then is it not always the case that when we play into these prejudices we are also harming ourselves? The need to isolate ourselves from those we perceive as beneath us or as different to us will always be an impossible ideal because we are always haunted by that which we perceive as dangerous to our wellbeing.

A better response to such an impulse, Adichie suggests, is to understand that we are all shaped by historical forces that are often too complex to comprehend, and that is why telling a single story about a person is dangerous.

It is in understanding and appreciating this complexity, it seems to me, that a more humane society might be possible and the fears that haunt us might be abated. For who else are we haunted by if not ourselves in others?

It will therefore be interesting to listen to Adichie on Friday at the Abantu Book Festival to hear where she is in her thinking. And whether I find myself agreeing or disagreeing with her will be a continuation of living in a complex world in which one is never fully formed. And dialogue, no matter how uncomfortable it makes one, is always necessary in ensuring that ideas are shared.

Publications

Publications

Partners

Partners