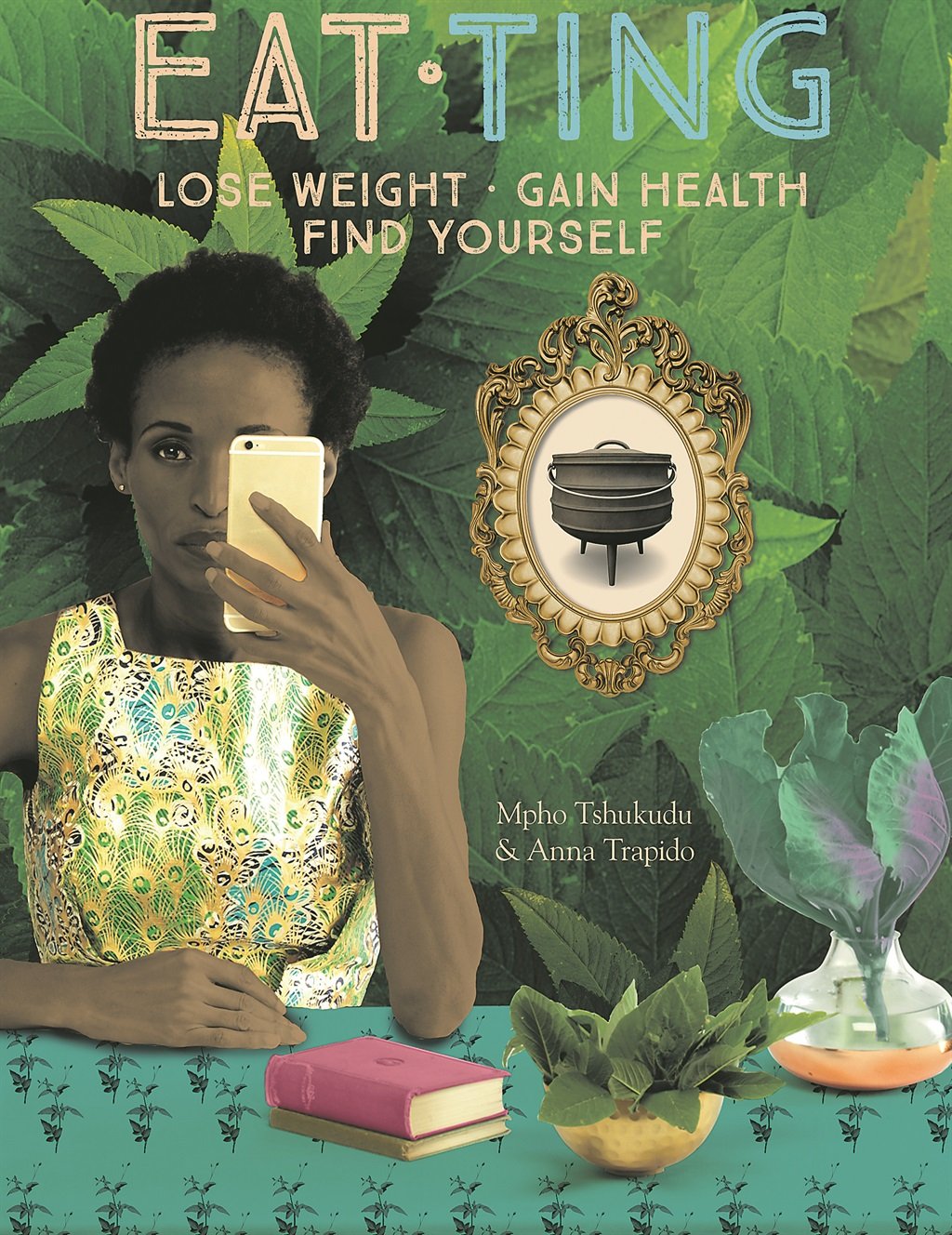

A new book by dietician Mpho Tshukudu and City Press food writer Anna Trapido is encouraging South Africans to get back to eating nutritional, traditional African food, writes Grethe Koen

Eat Ting

Mpho Tshukudu and Anna Trapido

Quivertree Publications

224 pages

R273 at takealot.com

Rating: 4/5

There are many powerful ideas in Mpho Tshukudu and Anna Trapido’s new cooking and nutrition book, Eat Ting, but the quote that best sums up the ethos of this beautifully worded and photographed manual is this: “Since we are what we eat, if we ignore taste preferences and familial food fondness, we become someone else. Essentially, the existing diet books serve up the idea that Africans need to change who they are to lose weight and gain health. This is nonsense.”

Eat Ting is the book we’ve always needed – a book that recognises black South African realities and actively promotes those beneficial foods we’ve been told we should no longer eat.

Dishes that your grandmother used to make, like slowly cooked tripe, offal and chicken feet. Low-GI legumes like tshidzimba (samp, sugar beans and peanuts) and dikgoba (cow beans and sorghum). Vegetables like morogo, wa thepe and amakhowe mushrooms. And, of course, ting (fermented sorghum porridge).

Now, not all traditional food is healthy – gemmer (ginger beer) and MaSkhosanas (scones) must still be consumed sparingly – and the writers are not saying that we should only eat traditional food (that would just be boring), but they are advocating that we disband the idea that traditional food is “poverty food”, or unsophisticated.

The way that traditional dishes are cooked and the fact that they incorporate so many good carbs, cultivated vegetables, and fermented milk and cereals, make them excellent for improving your health and helping you lose weight.

‘Poverty food’

What I love most about Eat Ting is that it is clearly based on people’s lived experiences. In fact, every chapter is interspersed with anecdotes derived from interviews with black South Africans.

One chapter addresses the seven problems that are making successful black people overweight and unwell. Among the universal modern-day issues of stress and a lack of time, black South Africans have kids who don’t know how to eat traditional food, which is frustrating when coupled with the obligation to eat at the “Triple M” – maso (funerals), matlapa (unveiling of tombstones) and magadi (lobola).

We also carry psychological scars from the past. Have you heard someone reject traditional food now that “re tlhabologile” (we are sophisticated)? Now-wealthy black South Africans generally know what it’s like to not have enough to eat and, not only do they never want to feel that way again, they want to make sure their kids never have to eat food associated with being poor.

A woman the author called Lebo writes: “When my husband and I were first together, we were young and we weren’t rich, but we had decent jobs and, for the first time in our lives, we had a fair amount of money. We both grew up quite poor and we just binged on everything. It was like, ‘Croissant! This is new! Let’s have 10!’ It was almost like a revenge thing. We were in hibernation mode – storing for winter as if the time of plenty would go away. But it’s silly because now it’s been 10 years and we need to calm down. Winter’s not coming. This is not Game of Thrones. The croissants aren’t going anywhere.”

Getting over that psychological feeling of “storing up for winter” means we must address it first.

And once we do, we will stop gorging on huge portions because we understand that the food is not going to run out overnight.

So did apartheid have anything to do with it?

What we eat and why we eat it is anthropological, cultural and political, says Trapido. Although global urbanisation has led to a rise in consumption of energy-dense, sugary foods (and an accompanying increase in body weight), South Africa is an even more extreme case because of apartheid.

Due to land dispossession, “families were split up and urban people no longer had access to the labour of grandmothers to cook, or younger sisters to collect firewood and gather wild leaves”.

Those who went to work in urban areas often lived in single-sex hostels where food was doled out by the employer.

Because of increased time spent commuting from black townships to white business spaces, there just wasn’t time for cooking any more.

Since slow simmering was no longer an option, people had to devise ways to add flavour to their food, which led to an increase in the use of stock cubes, powdered gravies and MSG (think Aromat).

The fact that apartheid outlawed land ownership and took away fertile farmland from Africans meant that there weren’t many black farmers around the urban centres producing indigenous crops, so even if you wanted to cook traditional vegetables, you couldn’t find them.

And then, perhaps the most insidious of all, was the arrival of state-powered mealie monopolies. Maize, the highly refined, nutrient-deficient and bleached kind, was pushed at the expense of other starches. This cheap, unhealthy food soon became many black people’s staple meal.

The good news is that bad habits can be broken. Urbanisation and acculturation might have introduced unhealthy food into our diets, but the power is in your hands to change how you eat; to take control of your diet and get back to nutrient-dense foods.

This might be the perfect book you need to get going.

Publications

Publications

Partners

Partners