Bad things happen to the men who date her. So runs the narrative about ‘difficult woman’ Kelly Khumalo. Most recently, she walked off stage at an EFF rally after the crowd started chanting the name of her late boyfriend, Bafana Bafana star Senzo Meyiwa. According to them, she is responsible for his death. None of it has been proven and yet the criticism of Khumalo continues. Sihle Mthembu looks at how we vilify women musicians.

At the time of writing this, it’s late March and Kelly Khumalo should be nursing a break-up with rapper Chad da Don. But she doesn’t have the time to do that right now.

She is preparing to go on stage for a solo show at Alice & Fifth – a posh restaurant and quasi-live music venue nestled in the lobby of the Sandton Sun hotel.

Here you’ll find a mix of “progressive whites” and the blacks of “woke Twitter” kicking their shoes off after a long day to take in some jams and sway under the spell of the establishment’s cloud-high domed roof.

As I sit in one of the green booths that circle a red table, I spot Khumalo out of the corner of my eye.

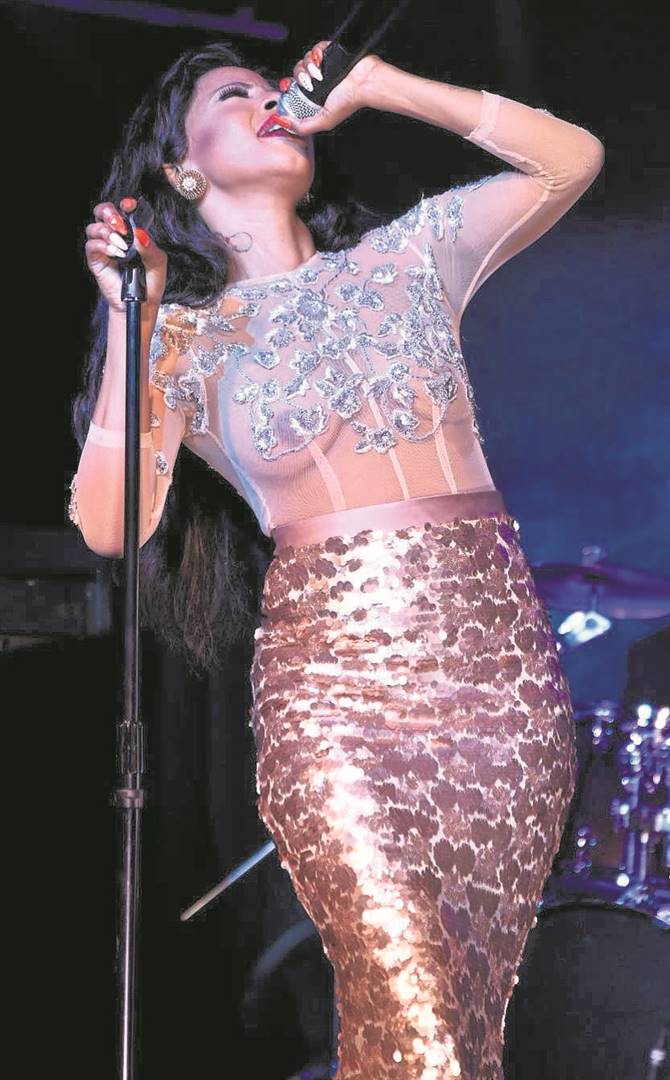

She’s on the edge of a makeshift stage, wearing a sheer beige top with embroidered appliques that barely cover her and a rose-gold skirt that looks like snakeskin.

Its layers glow and glimmer when enchanted by the charms of the stage lights. When she later posts a picture of the outfit on her Instagram – on which she has 1.3 million followers – someone is quick to remark that she needs nipple covers. She quickly replies. “To make who happy? You? Never! You hate it, then unfollow [me], it’s that simple.”

This has now become a part of Khumalo’s brand, this antagonistic relationship that she has with her fans, or at least with the people who follow her on social media.

Unfortunately, it is not a reflection of Khumalo’s actual persona. In person she is amicable and witty and has a curious obsession with detail that is a little off-putting if all you’re looking for are the bullet points.

Before she goes on stage, Khumalo is bobbing from side to side like a pendulum waiting to settle. From where I’m sitting there are only a few minutes left and there is a whole event being made of her eyeliner, or there seems to be something in her eye.

I think of that lyric by Prince in the song Erotic City: “Everytime I think of you / thoughts of you get in my eyes.” Down this wormhole I begin to wonder how often she thinks of her late boyfriend, Senzo Meyiwa, and what songs make her get him in her eyes. Because, since his death in 2014, Bafana Bafana soccer player Meyiwa is all people seem to think about when they see Khumalo.

When she eventually goes on stage, she’s more settled. She dances and turns, beguiling the audience with her mic control and vocals that surge into the night.

She engages in sing-talk conversations with a group of women seated closer to the front of the crowd than I am and this night is a fine example of one of the more understated powers of Khumalo as a performer. Moghel knows how to work the room.

There is no debate as far as pure talent is concerned – Khumalo is the best vocalist of her generation.

The control, range and apparent effortlessness with which she uses her instrument is the subject of intrigue and envy in the music industry. Why then is she still not well regarded? It’s because people wanted her to fail and she didn’t, but also because she is a “difficult woman”.

A music industry term repeatedly used to describe female singer-songwriters, often black, who rebel against the whims of an industry predicated on defining who they should be and how they should live.

Decisiveness

Khumalo has been through the ringer of violent relationships and drug addiction.

The highs of having multiple hit records and lows of relative anonymity and performing in small venues. She wears it all on her sleeve. Particularly on her latest album, Unleashed.

On the project she deploys her golden voice with deceptive skill. In the framework of the 12-song album she carves up a new lane for Afro-pop by departing from the layered and often dense west African rhythms that have come to dominate the genre locally in recent years and instead opts for a simpler, listener-friendly sound.

On the cover of Unleashed, she’s not looked healthier. She wears a white, lacey dress.

Her hair is tied up in a messy bun and her hands are held to the side straight and flat, permitting you to make out some of the writing of her tattoos, which include a cross and a third eye.

She looks directly at the camera, her gaze is neither confrontational nor vulnerable, instead it puts forward the theme that runs across the album – decisiveness. Here it is, this collection of 12 songs made by a woman who has seen the worst and refused to melt away.

If you’re looking for anthropology you will find no serenity here.

This is not an issues album. Perhaps with the benefit of time we will remember Unleashed as an animated musical map tracing the contours and folds that exist within Khumalo’s rich inner life. A life marked by finding joy and enflamed by a longing for a spiritual connection with a power much higher than herself.

If you’ve made it this far, you’ve done well. So let me reward you and let’s talk about the elephant in the room.

Senzo died on October 24 2014. The story goes that there was a robbery and Senzo was killed. Three unknown assailants fled the scene. This version of events and the timeline has since been contradicted several times by people such as music producer Chicco Twala, who was called to the scene shortly after the incident.

But whether you believe this or not does not matter, at least not right now. What is known is that Khumalo has since been blamed for Meyiwa’s death – apparently sending the three men to kill him. The narrative of the black woman who bewitches a man and lures him to his death via the magic between her thighs and the slickness of the tongue is as old as Adam and Eve.

The joke about Khumalo being a bad omen for the men with whom she forms relationships is a long-running one, but still bothersome.

It is not uncommon, even in this era, for people to say of a man who has problems that he should get into a relationship with Khumalo. The presumption is that something bad will happen and we will be rid of him.

This is not a new thing. In isiZulu there is term which says, “Okuhlula amadoda kuyabikwa”, which loosely translates to, “What has beaten the men must be referred to women”. At first this seems like a backhanded compliment remarking on the abilities of women to problem-solve complex scenarios.

But what is closer to the truth is, what we really mean when we say that, once men have tried to solve the problem and thoroughly messed up, women must come in to sweep up the mess.

On Brenda and Babes

And Khumalo has been our sweeper for a while now. We expect her to clean up after Senzo even in death. Real life, however, remains a lot messier than just that.

Men have their own agency and the historical benefits of patriarchy. It was Meyiwa who decided to be in that house; it was he who had moved out of his family home and left his wife to pursue Khumalo.

Perhaps that should be less of a footnote when we talk about his life in the months and weeks leading up to his death.

We are now entering the realm of speculation here. If, for a moment, we are to entertain the notion that Khumalo knows Meyiwa’s killers, we must also accept that this is about as South African an act as there is. It is not uncommon in the black community for us to know someone who has committed crimes and, because of the historical stain that comes with being a snitch, we say nothing.

Equally, our fear of prison and what it does to break black people, in particular, forces us to render empathy that prevents us from outing even the worst among those who have wronged us.

The morality of having a desire for justice is often weighed against the reality of having criminals who are also breadwinners ripped from the community. The latter wins way more times than it should.

So it is easy to lash out at Khumalo and egg her on to do something, to speak out. It is easy to project our failures on her because it makes them easier to manage.

“The fault, dear Brutus, is not in our stars / But in ourselves.” (Julius Caesar, Act I, Scene III)

The persecution of Khumalo reminds me of how we treated Brenda Fassie when her love, Poppy Sihlahla, died next to her while she was high in their hotel room in Hillbrow.

Headlines painted her as a bad woman, who used her power and voice to lure an innocent young woman into a den of sex, drugs and groove before robbing her of life. About the incident MaBrrr would later say it made her realise how much she wanted her fans to love her even as she was fighting them.

More recently, after an outcry following the release of a video in which kwaito artist Mampintsha beats up gqom queen Babes Wodumo, we have seen the tide turn on the young gqom artist and she has become the pariah of the story. In a recent performance celebrating her birthday at Durban’s Rich Durban Nightclub, the singer utters the phrase, “kukhona ingane lay’ndlini”, a term used by Mampintsha during the altercation which went viral.

For some this was an unforgivable transgression. With many Mampintsha loyalists and even some who supported Babes declaring that for saying these words she is worse than he is and is making a mockery out of the people who supported her and that she deserves to get beaten up. We refuse to see this moment as Babes taking back her agency after Mampintsha recorded a song using the phrase that he said to her repeatedly while stripping her of her dignity.

Punished

The female pop star as evil witch is a stale trope that is the product of society’s desire to bend over backwards just to prevent people in general, and men in particular, from being accountable for their actions and lives.

Our fascination with the pop icon as villain comes from a deep-rooted bias on the capabilities of women. We see beauty and talent as something that makes women incapable of certain things, including evil. So, when we think they’ve done something bad, the punishment dealt out is disproportionate and often swift and irreversibly severe.

When female artists make a mistake, the pleas that we cop for their male counterparts are never available to them.

That is because the music industry takes its cues from us, the buying public. From an early age, we treat boys as more valuable than girls. Entrust them with family names and install them as heads of the family regardless of age and their station in life.

In this business, the docile, passive performer, who owns nothing and says nothing is the only version of womanhood permitted to exist. Women like Brenda Fassie, Lebo Mathosa (who was often accused of wrecking relationships and turning young women into lesbians) and Khumalo are anything but docile.

We think of Senzo every time we see Khumalo, joyful and living her life without inhibitions and hate her. We boo her off stages not because we have any proof she did anything wrong or know something about Meyiwa’s death. We believe that her very survival and Meyiwa’s death robbed us and Meyiwa of his moment of redemption.

We had secretly hoped he would come back to his senses and label her as the homewrecker and go back to his wife; that Khumalo would stop living out so damn loudly and would retreat into a sheltered life marred by shame. Nothing vexes a crowd baying for blood quite like a woman who, put in fire, somehow makes it out alive.

Senzo had many moments to do this, to leave, and he chose not to. So, rather than deal with the blunt blow of that reality, we project our anger on to a woman who can do a lot, including spiral and bend her spine like a human slinky, but what she could not do then was make Meyiwa’s choices for him and she certainly cannot bring him back from the dead.

So, when we see Khumalo clashing with people on social media or getting off stage when she is booed, she is not merely attempting survival. She is hollering. Now it’s up to us to let her go.

Publications

Publications

Partners

Partners