Most people would agree that calling out racism, sexism, homophobia, transphobia or any other form of bigotry is necessary. However, the prevalence of 'call-out culture' has also created toxic online spaces that are not conductive to learning, and it has not been effective as one would hope it would be. Rhodé Marshall explores the complexity of what has become a double-edged sword.

For those who don’t spend their days and nights on social media, over the past couple of years, we’ve seen an increase of a brand of online activism called cancel culture, which takes user outrage and converts it into a large-scale rejection of someone – mostly a celebrity’s work, product or place in pop culture.

It usually involves tweets or social media posts calling on a particular person or brand to be wholesale boycotted or ignored due to criminal behaviour or bigotry. Users may tweet at brands this person is associated with, or lobby messages at the person themselves. This has affected many people in a wide range of situations, including rapper OkMalumKoolKat, film maker Khalo Matabane, and kwaito artists Brickz and Arthur Mafokate, to name but a few local examples.

On the one hand, this type of public shaming has resulted in so-called takedowns of public figures who have engaged in ghastly behaviour. It’s also been described as a thoughtful strategy because it puts power and agency into the hands of online minorities and consumers. But on the other, cancel culture has also become dysfunctional.

There is a growing group of people who strongly oppose cancel culture, suggesting that we should show compassion for people who make mistakes, and rather educate them and help them to do better in future. And then there are those who believe that removing our support is one of the ways in which cancel culture can become effective – hoping that this will end up with the person learning from their misdeeds.

There is also the question of whether, after someone is “cancelled”, when, where and how you disengage with their work, and on which merits it would be okay to welcome them back.

Former US president John F Kennedy once said: “Too often, we enjoy the comfort of opinion without the discomfort of thought.”

While cancel culture at its core is a well-meaning form of action, it can often become toxic because of the mayhem inherent in social media and the bandwagon activism on the platforms. And, truthfully, the debate and culture largely lives on social media in South Africa.

Outside of the online space, it feels like the culture is only really growing and being implemented in Joburg. So, while there are many sides to a story, let’s analyse cancel culture and its effects.

To cancel or to forgive?

Increasingly, people are questioning the relevance of cancel culture. Something that can be said for those who reject cancel culture is that they are instead trying to implement a culture of forgiveness and growth. But the question that they fail to answer is: What happens after the forgiveness?

They say the best apology is changed behaviour, something critics of cancel culture strongly believe, and should because it’s the only true reflection of change.

#Cancelled as a hashtag originated on black Twitter in 2015, and has been used to address a number of people (and products) deemed to be problematic over the past few years. While the #MeToo movement has revolved around abuse, it has also dealt with topics such as racism or queerbaiting.

When there have been call-outs, some have been more successful than others. An example of cancel culture is when the revival of the sitcom Roseanne got dropped by channel ABC after Roseanne Barr made racist comments on Twitter.

And then there are examples of cancel culture not affecting its subjects, such as rappers Kanye West, OkMalumKoolKat or R Kelly. Twitter users called for Kanye to be cancelled when, during an appearance on US entertainment site TMZ, he said that slavery was “a choice”, but his album still went to the top of the Billboard chart that year.

OkMalumKoolKat was convicted of sexual assault in Australia in 2016. Some Joburg promoters have stopped booking him, partly out of fear that the gigs will be boycotted or because they felt that the rapper didn’t give a genuine apology, but, in many parts of the country, he still takes to the stage. As it is, he’s continued with music, lending his voice to other artist’s songs.

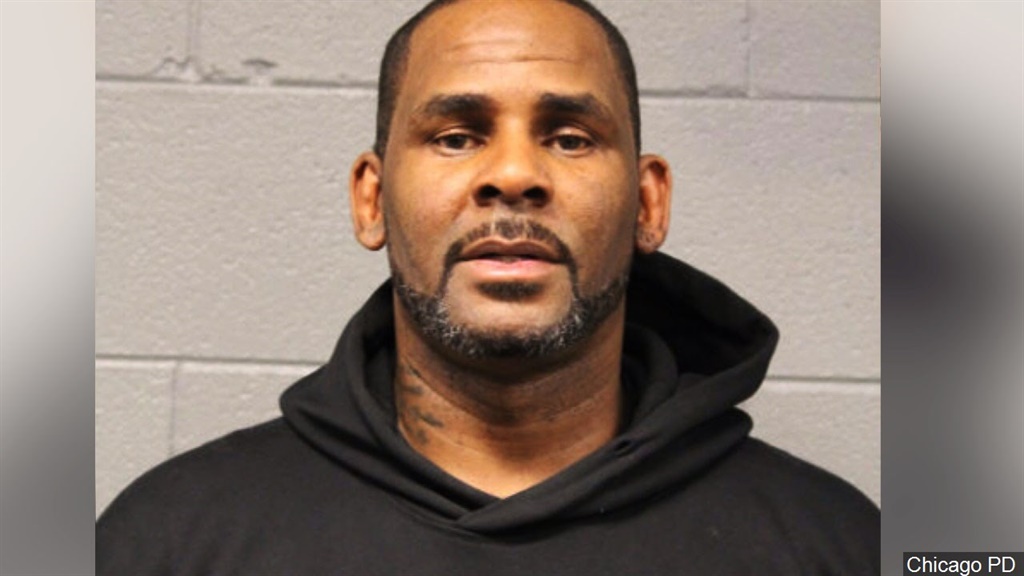

US musician R Kelly, who has been accused of sexual assault best summarised in the documentary series Surviving R Kelly and who faces multiple federal sex crimes charges and was denied bail on July 16 during a court appearance, has been cancelled for the alleged offences. But the cancellation, trumpeted via social media, didn’t immediately result in a real reversal of his popularity.

Online streams of R Kelly’s music increased 116% after the programme aired, a sign that you can’t expunge a legacy – however toxic it may be. He continued to perform and make public appearances, appealing to the public to allow him to make money to support himself and his family after some concert cancellations.

What does cancel culture really do?

I asked author of Born to Kwaito, Sihle Mthembu, whether calls on social media for artists to get cancelled were effective. Mthembu is an outspoken pop-culture voice and has a good grasp of South Africa’s musical landscape and artists.

“I think targeting individuals with cancel culture is easy, but, ultimately, it lacks impact,” he said.

“At the core of it, we need to target the corporates that back and support problematic people. It’s one thing to say ‘I won’t watch a movie by Woody Allen’. That’s an individual action and it’s a great gesture, but, ultimately, we have no way of knowing that you’ll actually do that in the privacy of your own home. That’s why people can say someone is ‘cancelled’, and yet their music streams go up – people don’t really follow through. But with corporates, when we cancel them or pull our money, the impact is significant and tangible, and we can see this in real time. Ultimately, it’s the companies that give monsters power by continuing to back them.”

Mthembu says that Allen was the reason he started making movies, however, he had to re-evaluate him as a figure after allegations emerged that he sexually assaulted his seven-year-old foster daughter. Allen also raised eyebrows when he married his stepdaughter – who is 35 years younger than him – in 1997.

“The more I’ve learnt about Allen, the more I’ve realised he is such a creep and that it’s coded in all his work. I’m not interested in digging my head in the sand and saying that he is cancelled – we will never watch or engage with his work again. Rather, I think we must run to the work to really get a clearer understanding of how such predators operate and hide in plain sight so that, hopefully, we can identify those signals in the work of others in the future. If we disengage with the work of people whose values do not mirror our own, we risk not learning, and then only realigning when it’s too late. Then we’re just repeating the cycle,” said Mthembu.

So the cycle continues and plays out in our everyday lives, but does this have any real impact on the way people behave, or are we just shouting at one another within a social media bubble?

Real justice?

I spoke to award-winning film maker and historian Palesa Letlaka about whether cancel culture is effective. Letlaka was one of several women who accused film maker Khalo Matabane of sexual assault, bravely penning an open letter to him that detailed the many forms of harassment she was subjected to.

“It depends on what you define as impact and how you measure that,” she said.

“Are you including emotional justice as an impact for women who have spoken out within a patriarchal society of violent masculinities that relies on silences and censures, which makes it terrifying and even life-threatening to speak out? Are you then including the impact of breaking the silence in a patriarchal society?

“The issues involve individual celebs or prominent men, but are bigger than the individuals and are really about a complexity of issues regarding rape culture. It asks us to examine the milieus and factors within society – silence and the reliance on women’s silence being a big one – that have been the enablers of existing patterns of behaviour in any designated group – the families, communities or cultures where the sexual assault of women is normalised. Comments like ‘it’s the way kungakhona’, or ‘it happens to every one, wethu’ – that downplaying of sexual assault,” said Letlaka.

She pointed to her own experience with breaking the silence around Matabane as an example of the trivialisation of sexual assault.

“A woman I know from the film industry and I were chatting and she referred to what I had experienced as ‘forced kissing’. I asked her to imagine an instance where she was in a mall and a stranger came up to her, rammed his tongue down her throat, groped her body and buttocks and wouldn’t let her go. Would she call that a ‘forced kiss’ or a sexual assault?”

Who gets cancelled?

Privilege, particularly male privilege, plays a big part in whether someone gets cancelled and even to what extent they are cancelled. Cancel culture at its core tries to defend the minorities which, in the past, have had to endure being enslaved, abused and erased – and this helps them to reclaim their power and fight back. Most often, the “victims” of cancel culture are people who are expressing some kind of privilege.

James Gunn, arguably one of the most famous examples of cancel culture, was rehired by Disney to work on Guardians of the Galaxy after being fired for joking about paedophilia. It seems that many are called out, shamed and then seamlessly go back to lives, which raises the question: “Is cancel culture real and, if not, why does this keep happening?”

Letlaka feels the politics of credibility between men and women needs to be looked at.

“We have to look at if it is possible to have the power of being a ‘credible woman’ when the onus is taken away from the perpetrator’s actions, and the burden of truth and proof gets shifted on to the survivors of a sexual attack – in the courts, outside of the courts and in public spheres, including social media. We must look at the nexus of factors related to why men go on performing or working as before despite being called out for sexual assault,” she said.

In its current form, the act of cancelling someone is still mostly socially performative because the declaration that they are cancelled does not necessarily force a change in behaviour.

Kimberly Foster, the founder and editor in chief of the blog For Harriet, looks at the idea more broadly in a video called We Can’t Cancel Everyone. She points out that isolating people does not undo the harm they’ve done, and that it’s necessary to differentiate between individuals who said offensive things and the institutions that stripped people of their humanity – the latter being far more destructive.

“Changing culture meaningfully means approaching folks from the standpoint of ‘these harmful ideas you are perpetuating need to go; we’re not going to accept this any more’. But the people themselves can be recovered,” she says.

The moral panic

Morals, values and beliefs are the essence of the decision to cancel someone or not – not outrage or peer pressure, but an individual’s point of view. You could be angry all day at a racist or sexist celebrity, but if their fans don’t have the same values that you do and care less than you do, they won’t be cancelled.

This goes for most people who end up being called out, and then all you’re left with is instant gratification that quickly fades. Or perhaps we should admit that properly calling out someone to the point where it has real societal impact comes down to our personal biases and beliefs.

If most people on social media are honest with themselves, they should be able to admit that they can forgive someone based on their experiences and personal apology language.

Cancelling and forgiveness isn’t as cut and dried as we have made it out to be, and so we’re stuck in this grey area where some are held accountable and others are not, and where the conversation doesn’t extend beyond the internet and big cities.

A local example is Molemo “Jub Jub” Maarohanye, who made an astounding return to fame and favour after he and a co-accused were convicted of culpable homicide in 2012. The two were drag racing in Protea North, Soweto, in March 2010 when they crashed into a group of schoolchildren, killing four and seriously injuring two others.

Since his release in 2017, Jub Jub has been keeping the nation entertained with the success of the controversial TV show Uyajola 9/9. It seems as if it didn’t take much for Jub Jub to become Mzansi’s “It boy” without knowing whether he has been properly rehabilitated (let’s be honest, prison is no rehabilitation centre) and is safe to accept back into society – something not even his inner circle is entirely convinced of yet.

While cancelling someone often happens after a rush to judgement, cancellation does not always suggest or need moralism, or reckless impulses – it only necessitates reckoning of the truth as it is.

Mthembu said: “A new reading of an old work as what we know about the artist and what we think of them is very useful. In many ways, it’s much more useful than pretending that that work does not exist. Amnesia is neither activism, nor is it a solution for trauma.”

So can the cancelled be uncancelled? I’d say yes – if they are willing to do the work. Or hire a great publicist.

Publications

Publications

Partners

Partners