Acursory academic search of postgraduate studies on the tokoloshe is as disturbing as any random scene from acclaimed film director Darrell Roodt’s 2012 TV series Room 9.

Judging by the names of the postgraduate students, it appears that about 90% of them are white men, many of them Afrikaans.

The same is true of the self-published books on the

subject that litter Amazon with half-naked black maidens traumatised by the hairy, horny creature that is rooted in African oral culture, a dwarf-like and mostly malevolent spirit.

The bricks under the maid’s bed

In Room 9, a poor replica of The X-Files but on a Porta Loo budget and without the sexual tension, or any other kind of tension for that matter, domestic workers (in French maid outfits) in Killarney sleep with bricks under their beds so that the tokoloshe can’t climb up on to them.

Aside from Daily Sun posters, this is the enduring cliché of the white tokoloshe experience and it stems from separate development and exploitative labour, where live-in domestic workers serviced white families.

Despite the head writer of Room 9 claiming in a US interview that the series “had a pretty huge impact” in South Africa, in truth it dropped with a thud.

“Every episode that was screened was trending days after,” he said. Perhaps. But he failed to mention that it trended for all the wrong reasons.

In Room 9 the tokoloshe was lined up for cheap US thrills, alongside “poltergeists, zombies, aliens, demons and other myths, such as Zulu vampires and mermaids”.

It had about as much cultural depth as a Petri dish because its head writer basically saw the tokoloshe as a kind of werewolf, which originates in Indo-European mythologies and emerged in pop culture in Medieval Europe.

Displaced from its cultural roots, it becomes just a device to deliver shock and horror.

Or laughter as it turned out.

Scare the shit out of the natives

But Roodt really has nothing on Leon Schuster, the enduring funnyman of South Africa’s silver screen and still the biggest hitmaker in our cinema history.

In his candid camera spoofs, Schuster has staged gags where an actor playing the tokoloshe is hidden inside a suitcase which is left by German tourists at a traditional marketplace.

Speeding away on an emergency, the suitcase is left behind and the curious natives circle it, only for the tokoloshe to jump out and terrify the bejesus out of them.

What Schuster does is appropriate a culture and then add insult to injury by traumatising them with it.

It’s been this way since the beginning of white South Africa’s tokoloshe obsession, which can be read as either an extension of white fear or white obliviousness. Cue Bill Faure’s Shaka Zulu and just about every video put out by Die Antwoord.

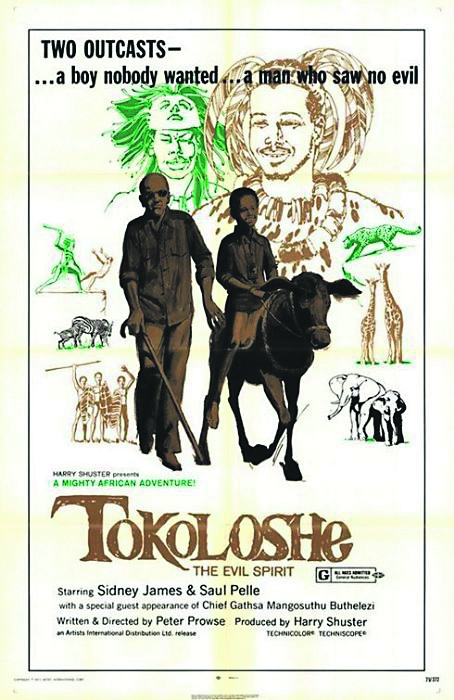

The 1965 film Tokoloshe sets the tone.

“A young African boy is rescued from a witch doctor’s death curse. He travels to the big city where a blind white man becomes his protector,” reads the official summary. Enough said. The mainstreaming of African folklore is an extension of the colonial project, even if Mangosuthu Buthelezi stars in it.

Film critic and film festival programmer Sarah Dawson has studied horror and B-Grade film.

“Oral culture is different to mass media, such as newspapers or film, in that the former is unconstrained by institutions flowing freely between people who talk and people who listen. The latter, though, emerged with the invention of patented technologies, such as the printing press and camera, around which developed industries and conventions that allow for mass reproduction,” she said.

“Importing images that come from oral culture into mass media needs is, therefore, treacherous unless one understands the deep structure of racism that underpins the film conventions we take for granted.

“Films like Get Out show that it is indeed possible to use the conventions of horror reflexively to subvert racist structures, but this is careful and self-conscious undermining and inversion of years of abuse. Unfortunately, the image of the tokoloshe in South Africa is used, more often than not, in ways that are incredibly patronising.”

“Tokoloshe haunts mlungu!” shouted a Daily Sun poster many years ago. As if in retaliation, mlungus then haunted a tokoloshe when masters of appropriation Die Antwoord were commissioned by Vice magazine to investigate tokoloshes.

The return of the tokoloshe

Now, like Shaka Zulu, the tokoloshe is having another global cultural moment and, really, not that much has changed, because the beast has already been dislodged from its culture and turned into a Westernised horror device and little more.

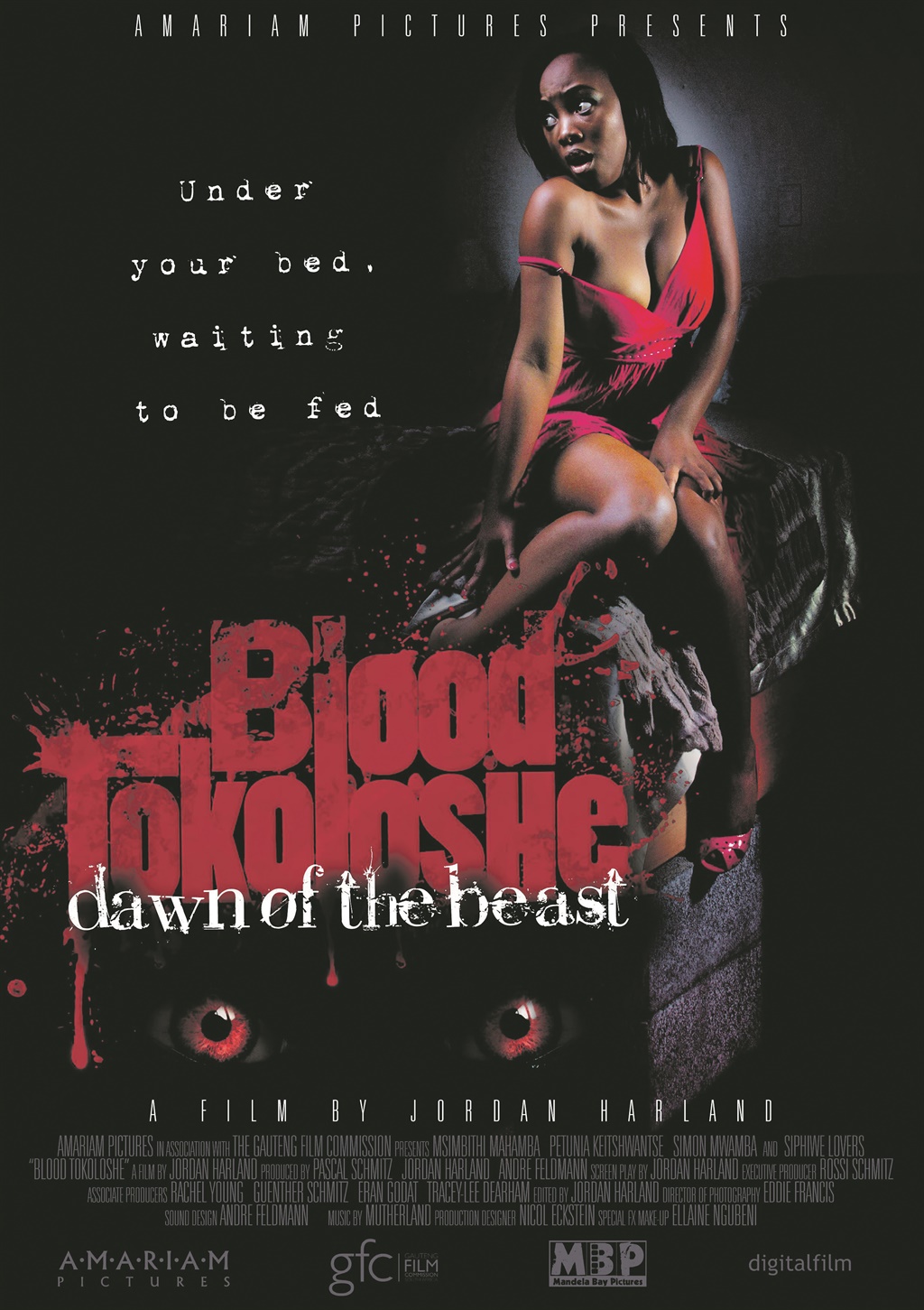

Blood Tokoloshe, filmed in Orange Farm and released in 2013, is full of B-Grade joy, but plays out like a US cornfield slasher, its Hollywoodification so pronounced that it was internationally released as Ghetto Goblin.

In the film a man gets a sangoma to make him a tokoloshe so that he can get sex and money. Of course it all goes wrong and he makes one wish too many. His calabash overflows with blood and the serial-killing tokoloshe goes on a babe-slaying rampage.

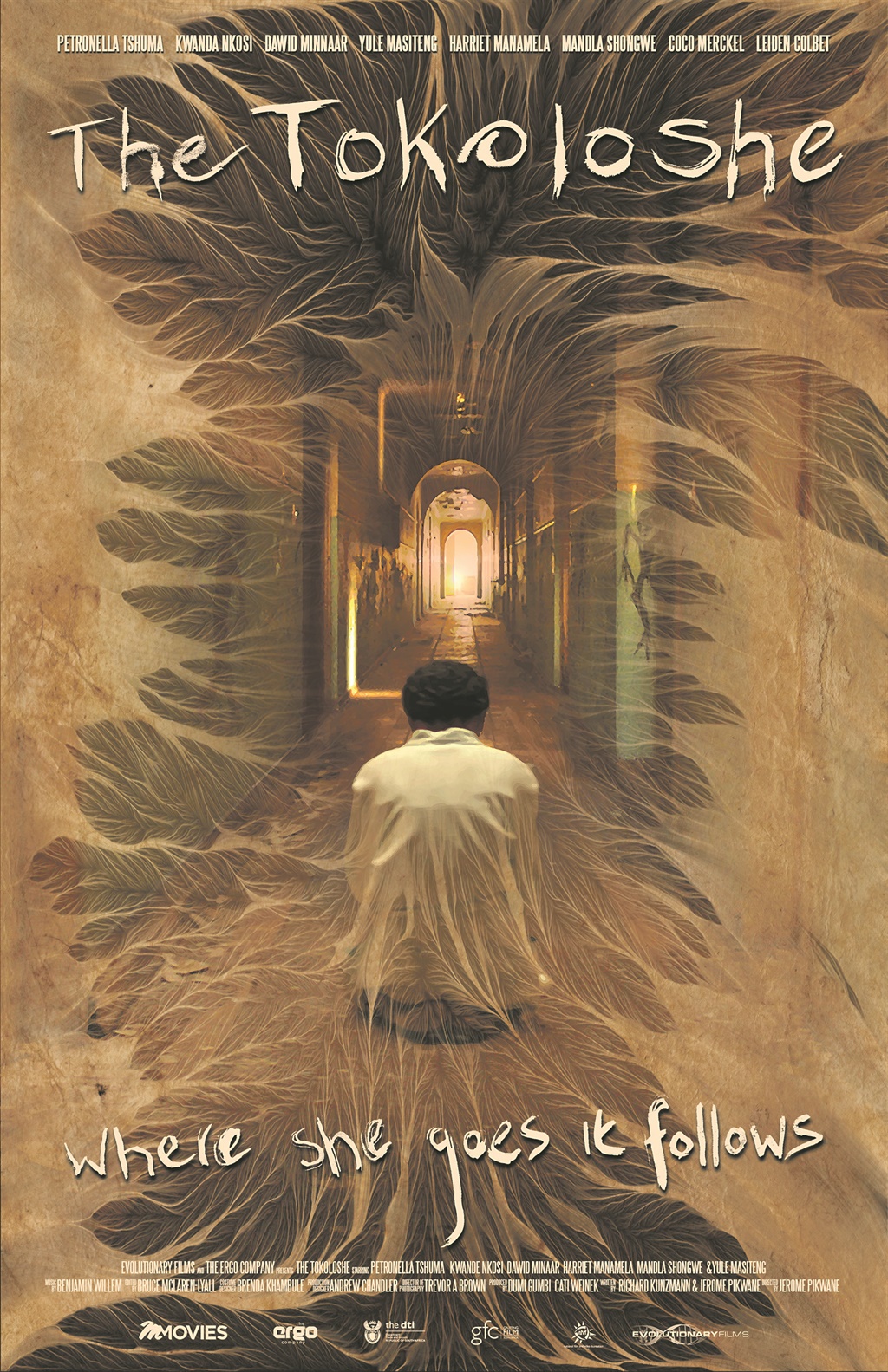

Another new feature coming this year, cunningly called Tokoloshe, gives all appearances of perpetuating the same US formula, though I might be wrong.

There is perhaps some hope, though. The first black director of a tokoloshe feature – The Tokoloshe (2018) – Jerome Pikwane opted to make a psychological thriller version of the mythology that will sell in other countries and indeed the tokoloshe is now just another troll under the bridge. Pikwane’s film has been snapped up in South Korea, Canada and Europe.

“The tokoloshe means different things to different people and different cultures,” said Pikwane. “So we had to create our own mythology for it from our research ... The film explorespatriarchy,” said Pikwane, who was born in Kimberley, raised in Joburg and studied film in New York. In his film Busi must deal with her own childhood abuse to conquer the creature.

“Horror films can be a catalyst to deal with ills in our society. Jaws took on Nixon, Get Out took on race relations in the US and The Tokoloshe represents the systemic abuse and oppression of women by masculinity. The black woman, in particular, is the most marginalised sector of our society,” said Pikwane.

Jaws might have taken on Nixon, but it also horrified sharks, further endangering them and projecting them into the landscape of fear.

The most positive aspect of Blood Tokoloshe was that its producers – Pascal Schmitz and Mayenzeke Baza – used the project as a community film development vehicle, empowering local film workers and attempting to create a sustainable, black-owned project.

Box office blues

In truth the run of genre films in South Africa at the moment is a failing attempt to build some sort of pop traction at the box office.

“It has been part of the persistently misguided idea that if we just do South African rehashes of popular US genre films, audiences will start making it rain Madibas at the box office,” said Dawson. “But its difficult not to see the invention of the kasi horror monster – by mostly white film makers – as a projection of their own sense of the ‘creepiness’ of African mythology being forced, without any nuance, into the deeply representationally problematic mould of popular film.

“The scariest and most poignant horror scratches at the fears that live just under our society’s skin – such as films about mutants in times of nuclear tension, or disaster films in times of climate change.

“If local resonance is the primary concern in seeking to creep out emerging black audiences in South Africa, surely something like the ghostly return of a puritanical Victorian missionary who refuses to pass on to the next world would be a far more terrifying spectre in this context – one which tapped into the real unconscious anxieties of our young nation. But this would require associating whiteness with a transcendental, pure form of evil, but this runs against the grain of the institutions and conventions of mass media, which for centuries has been to deflect everything ugly, evil or perverse away from whiteness on to images of people of colour,” said Dawson.

Publications

Publications

Partners

Partners