According to a recent report, the South African games sector is worth $1.3 trillion – bigger than the music and film industry combined. But besides just expensive internet, there’s a lot still holding us back from being the global force we could be, writes Grethe Kemp.

Games are big, in case you didn’t know. A 2015 to 2019 report by PwC showed the digital video games sector as one of “the biggest success stories” in South Africa’s entertainment and media industry.

But few of us are cognisant of its massive reach and even fewer of us know about the wonderfully successful games being made within our borders.

Ben Myres is the co-founder of local gaming studio Nyamakop and the former curator and program manager of annual local and African game showcase A MAZE. Myres says although the local gaming industry is successful, most local developers gain revenue – and recognition – outside South Africa.

“Local game developers for the most part don’t focus on gaining revenue from local consumers, because it’s a very tricky thing to do,” he tells #Trending.

“In 2015, of the R3.6 billion spent on games in South Africa, only about R70 000 went to local developers. A lot of them have a model of making games for a lot cheaper than you could in the West and then putting it online and selling it to the world.”

And there’s money to be made here.

“In Cape Town, Free Lives made a game called Broforce that sold about a million units across platforms. That’s probably the most financially successful work of art to come out of South Africa.

“They’ve had some press, for instance they were featured on Carte Blanche, and there are those from the mainstream press who write about the game scene every now and again, but it really hasn’t hit the public in terms of understanding.”

But was Broforce a once-off or is the industry actually viable?

“It’s quite lucrative right now,” says Myres. “We’ve had plenty of games that have been really popular and successful. Another one that comes to mind is Viscera Clean-up Detail, a parody-satire of Western sci-fi films where you clean up monster massacres.”

Nyamakop’s Semblance received massive praise and has a 9/10 rating on the popular online gaming platform and store, Steam.

“Semblance was our first game that we made in our final year of university,” Myres says.

“We saw it as a way to break into game development as a whole and gain an international network of funders and press people. And it really did that for us. We were covered by all the major gaming sites, including by publications like Forbes, The Verge and Rolling Stone. It was rated the 68th best PC of last year, according to aggregation site Metacritic.”

On the student front South African games are winning major competitions overseas.

After Hours, created by 24-year-old Bahiyya Khan, deals with women abuse and mental health. A huge departure from the action and male-dominated narratives we usually see. It features artfully shot videos and deals with significant social issues.

Khan won best student game for After Hours at the Independent Games Festival (IGF) in San Francisco in March this year. Since then the game has just kept succeeding.

“I never expected After Hours to take off as much as it did,” she tells #Trending. “After showcasing in San Francisco, it generated so much interest that it feels almost like a social duty to put it out on as many platforms and make it as accessible as possible.

“Right now, I’m registering as a company before I can put it up on Steam. There’s a lot of legal stuff required.”

As a Muslim woman of colour from the south of Joburg, Khan stands out in an industry dominated by white, usually male, developers. As such, she’s often questioned about representation in the games industry.

“I do get tired of being the ‘poster child’ for representation,” she says. “I feel like constantly answering those types of questions makes you feel as if you’re just another marginalised product. You’re just there to make the events look good – because they’re usually literally a white-bro fest.

“But at the same time I often feel angry that I’m so set back in a lot of ways. I started my degree in 2014 and I didn’t have internet from the beginning. I came from a really bad public high school.

“Coming to Wits we did a lot of art theory and everyone seemed to know what was happening.

“I always had to work a lot harder than everyone else, which makes you burn out quicker and I feel like it makes you angrier and way more cynical about a lot of things.

“Sometimes I feel like I can’t make any mistakes because you almost represent everybody who identifies as you. It’s a lot of pressure, especially because I’m so young and so new to all of this.”

Working in a vacuum

Khan’s background is more in line with that of most South Africans and the issue of privilege in game development is something echoed by Danny Day, the developer and creator of Desktop Dungeons: “In South Africa we have a lot of people from previously and presently disadvantaged communities who grew up playing arcade games, but there’s little support for them to step beyond that.

And that’s an issue that the local games industry alone can’t address.

There also aren’t scholarships and bursaries and the kind of support that would be needed to reach across that privilege barrier and pull people through. Universities like Wits are starting to do that, but university courses aren’t necessarily the best way to be exposed to the business of making games.”

Day says another problem is the decline of Interactive Entertainment SA (IESA), the industry body for games in SA.

A huge part of turning your game into a success is to take it to international trade shows. Unfortunately, travel and business funding has declined. Part of that is that IESA’s funding has been restricted.

“We received news last year that IESA is no longer going to be able to apply for business and travel funding, because the government doesn’t see it as being successful. They’re expected to fix the education system to convince the government that it should get funding to grow the games industry, which is obviously not viable.”

Day says another problem is that the local community is no longer as useful as it used to be in giving feedback on developing games.

The easiest way to see if a game is viable and worth investing in is to have as many people play it as possible and give feedback. The local community used to be a very involved place, but it’s declined lately.” Day says.

Putting your creative work out there for others to critique seems like a nightmare, but it’s a vital way to gauge if it will turn out to be something other people – not just you – would want to play. And without that feedback, you’re just working in a vacuum

“What I’m expecting is to see more local games come out and fewer successes. We need good feedback; we need people to stop building their game and be the only person to see it. Every game built without player feedback has a massively reduced chance of succeeding.”

Getting off the ground

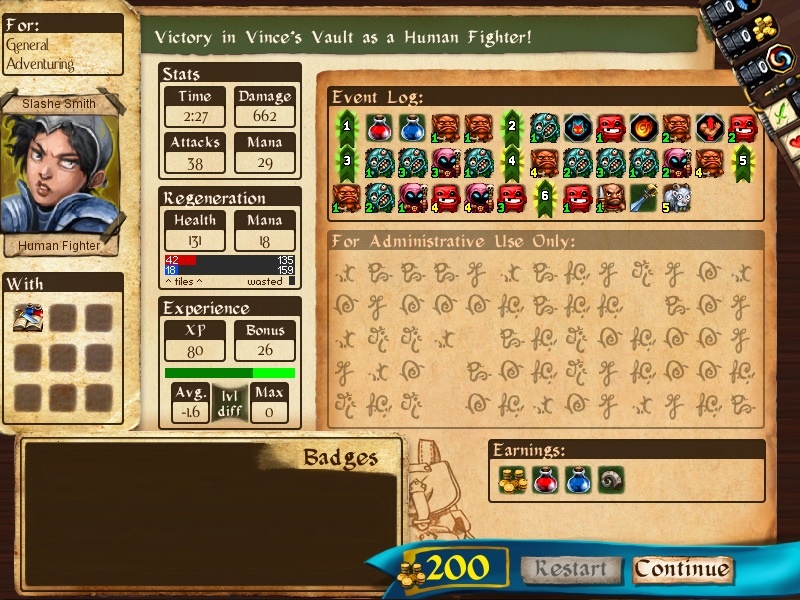

Day’s successful, highly rated single-player role-playing game, Desktop Dungeons, cost R2.6-million to make over five years. A sum he says sounds like a lot, but is actually nothing.

“In the international space if I tell people we spent $250 000 on a game that won an IGF, they’re like ‘What?’.”

The truth is, games are an expensive product to make, and you’re going to have to be able to spend a great deal of time in development before you see any returns.

For this reason, you have to have a certain financial situation before you can start: “The five of us were severely underpaying ourselves,” says Day. “But at the time the costs of building things were very much amortised by our having places to stay and living cheaply. And that’s why privilege is such a key factor in building games in South Africa – you need to have a place to stay and resources.”

And where do you get those resources?

“It’s either sweat equity where you’re building something part-time or as a hobby project, or you’re literally just burning through cash that you’ve saved from somewhere else.

It’s very hard to convince someone to give you funding for a game idea.”

Lack of support aside, if you have the grit and passion to make a game, the best way to start, is just to start:

“There’s nothing stopping you from jumping in right now,” says Day. “All the tools that we use professionally are out there to use for free. You should download them and do as many tutorials as you can.”

And a portfolio will be your most valuable tool when it comes to approaching gaming studios, like Day’s QCF Design.

“Building a portfolio is massively useful because even if you don’t go into the industry, learning to make games teaches you how to code, which you can use for a variety of other jobs.”

And, as with all creative industries, you have to have the passion and heart for it.

“It’s a calling, it’s not necessarily something that you can sit down and run an accounting process on and say ‘this is a great thing to do for the rest of my life’.”

Oh, and don’t worry if you don’t fit the ‘game developer’ profile. I asked Khan what she would have told her first-year student self: “I would tell her she’s extremely enough. And that she does not need validation from all of those white boys in her class. And that she’s not just going to be okay, she’s going to be great.”

- To find out about gaming meetups in your area, visit Make Games SA at makegamessa.com or follow them on social media. No experience or skill is required to come, just curiosity

- Reports used: Serious About Games report 2017; PwC Global Entertainment and Media Outlook 2015-2019

While Broforce was our most popular export, its characters – a clever parody of hypermasculine action hero-style commandos from US films – aren’t exactly representative of South Africa.

So, do we have unique aspects that set our games apart?

“I’ve been told overseas that there’s a South African style to games – and that’s a specific kind of humour,” says Danny Day. “Desktop Dungeons and Broforce are produced from a perspective that is outside of what people would expect from the US, EU and Asian industries. As long as we embrace our own South African reactions to things then they will be different and strange and often that strangeness can be super useful.”

And sometimes it’s representing the real – albeit uncomfortable – issues that face us as a country.

Says Khan: “What inspired me to make After Hours is all the terrible violence against women in our country. We’re taught in university to make games that appeal globally, but what After Hours shows is that the world is ready to receive games that aren’t necessarily so ‘Western’.”

And as South Africa enters the main stage, do developers feel a responsibility to make games that are representative of the country?

“I generally get very irritated when people represent Africa as being this dusty place with animals walking among us,” says Kahn. “Obviously, some people do have lives where they interact with animals and if that’s the game you want to make that’s fine. But that’s not the game that I’m looking to make. I make games with which I’m able to identify. And I feel like if you’re doing that as a South African your game is inherently South African.”

And the truth is, if we want games that show characters representative of a diverse South Africa, the industry needs to become more diverse. As Day says: “When I see studios trying to produce something that’s culture specific, I want them to be hiring young black people to do that.”

Publications

Publications

Partners

Partners