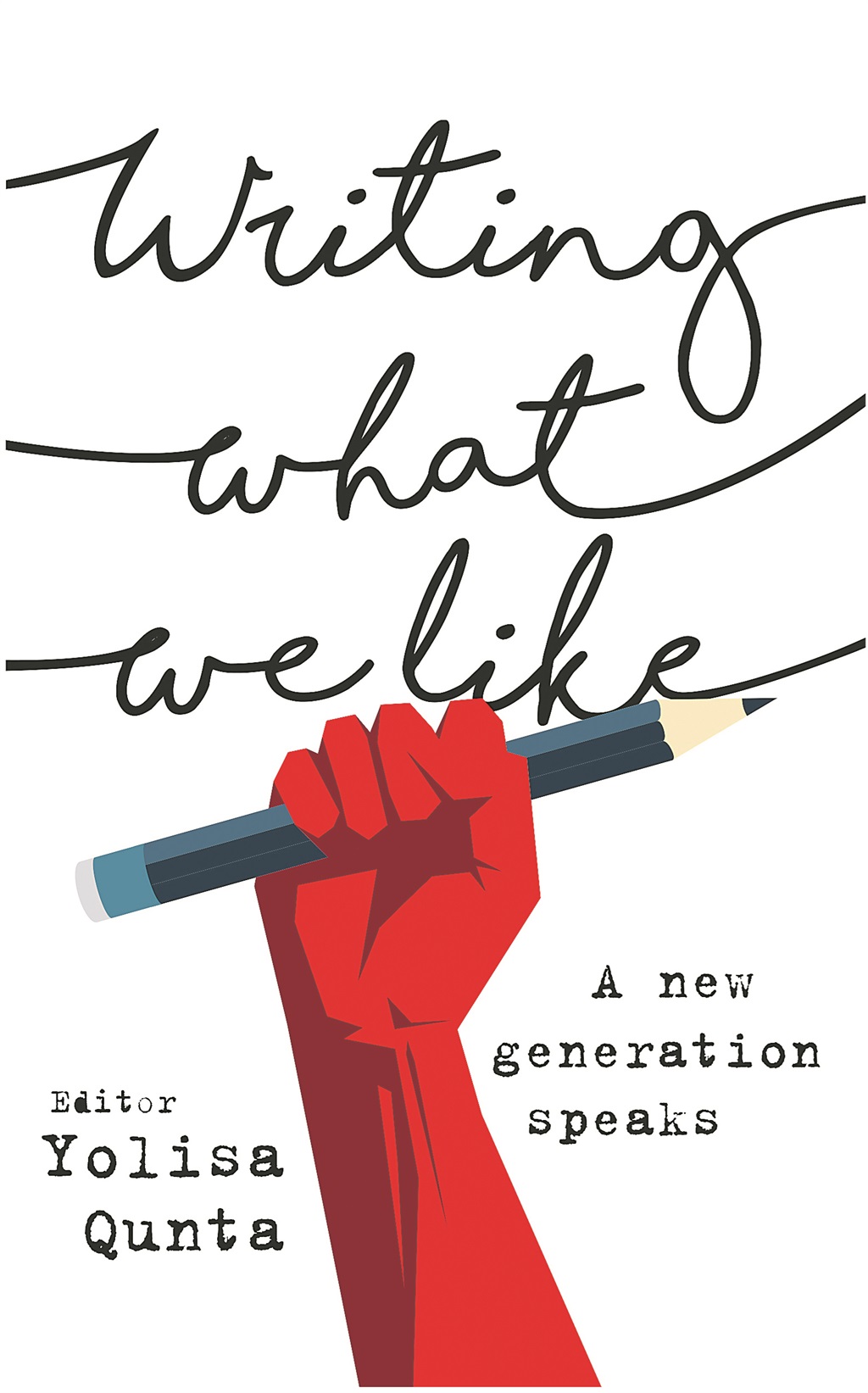

Books and music arm each generation with the tools to tackle the social issues of their day. In this extract from a new book called Writing What We Like, Lwandile Fikeni considers growing up in the former Transkei and finding political consciousness

Writing What We Like: A New Generation Speaks edited by Yolisa Qunta

Tafelberg

224 pages

R180 at takealot.com

The first time I read Steve Biko’s I write what I like, I was lying naked next to a woman in her university residence room. It was the morning after; I’d reached for one of a handful of books on her bedside table.

Reading the first few essays left me terribly nervous. As a black student at Wits in the early 2000s, his condition was familiar to me. Lost in the corridors of whiteness, questions of race and identity preoccupied my and my fellow black students’ minds. I was sixteen and on my way to dropping out of a BCom (accounting) degree.

Growing up in the former Transkei, we didn’t preoccupy ourselves with whites. We were a homeland – a Bantustan – and few whites in our town were neighbourly.

In many ways, they had assimilated into our culture. Generally, whites in the Transkei knew how to behave, and still do. I suspect it’s due to the idyll of the lush Wild Coast, the famous rolling hills of the Mbhashe, and the respect that Xhosa culture demands of those who coexist with Xhosa people. We called elderly black women and men ‘Mama’ and ‘Tata’, respectively. It was ‘Sir’ and ‘Ma’am’ for our white and coloured neighbours. Whites learnt our language (to a commendable degree), lived in our neighbourhoods and went with us to school.

Once I got to university, however, I realised two things.

Firstly, whites were evidently more privileged than blacks. Secondly, the peaceful race relations I was used to were not a reality at Wits. Violent incidents took place. A black student would be attacked by a group of white students, with no punishment meted out to the perpetrators. The white students would continue to attend class, with a smugness that betrayed their knowing something we didn’t.

And I guess, to some extent, they did. These were the dynamics of South Africa: whites were accustomed to being superior to blacks. I must confess, this was something I wasn’t used to. My only exposure to it had been on trips to East London, when my mother and I would go to visit my gran, who owned a shebeen in Mdantsane.

Although East London (near the former Ciskei) was in our back yard, we’d have to cross the border into South Africa to go there. At the Nciba border, now called the Kei Bridge, we’d suffered terror and humiliation. My mother had never betrayed any fear of the white boys in khaki uniforms, who had carried impressive automatic rifles and sported ridiculously thick moustaches and Charles Bronson-style sunglasses. Unlike Bronson, though, they carried real guns. These white men stood in stark contrast to Uncle Jimmy, the Portuguese man who owned our favourite fast-food shop back home.

They would rifle through my mother’s luggage with their weapons, and fling her petticoats and bras and my PJs out onto the road while the rest of the taxi passengers waited their turn. These border patrol officers seemed young – well, younger than my mother, whom I feared and respected and loved all at once. I never understood why those boys behaved the way they did, or where they got the balls to carry automatic rifles in my mother’s presence. Or, more importantly, why their faces displayed such contempt for us.

It was at university that this inexplicable contempt started formulating itself into questions about race, power and social inequity. We sought political consciousness in the sweeping debris of student life in Braamfontein, a life punctuated by drunkenness and debauchery during the HIV scourge that threatened to snuff out our young lives with such indifference that we were forced to articulate the conditions of our fight for purpose and identity.

We had to confront, nakedly, our own blackness and the violence that aimed to destroy it. Instead of shrinking in horror from this insurmountable task, we chose to celebrate and explore it. In Braamfontein we began, in earnest, to play with things to which we’d had no access only a decade before. Having just missed the kwaito wave of Mdu’s Tsiki Tsiki, Arthur Mafokate’s [Don’t call me] Kaffir, Boom Shaka’s It’s About Time, Joe Nina’s Maria Podesta, Thebe’s Tempy Life, Brothers of Peace and Crowded Crew, we slipped, quite deliberately, into American hip-hop.

With hindsight, it seems a logical progression for us to have extended our tastes, in the early 2000s, to conscious black American hip-hop. Over there, they were free – seemingly just as we were – but, like us, not truly free. We dipped into Mos Def and Talib Kweli’s album, Black Star, Guru’s Jazzmatazz, Public Enemy, Erykah Badu, Lauryn Hill and A Tribe Called Quest.

While the kwaito generation, of which we were a little part, liberated itself with every street bash, we were seeking ways to re-educate ourselves with hip-hop records and books. We read Dambudzo Marechera’s House of Hunger as a metaphor for our impoverished material condition and moral depravity. Tsitsi Dangarembga’s Nervous Conditions hinted, for us, at the need for feminism and led us to question our privilege as young black men.

At Wits, we were suspicious of our white lecturers. We believed that they failed us intentionally, which we could never prove. We may have been free, but I couldn’t help seeing, in every stare from a white person at Cresta Shopping Centre in Northcliff or The Waterfront (now Brightwater Commons) in Randburg, those boy soldiers and their Charles Bronson moustaches. Our white peers’ contempt seemed to be lodged in something deeper than the politics of colour.

Clashes between black and white students in pubs in Arcadia and Hatfield in Pretoria gave us a sense of solidarity with students at the Pretoria Technikon (today, the Tshwane University of Technology) and the University of Pretoria. We may have made it into these hallowed institutions of higher learning, but we were still unwelcome. At Pretoria Technikon, The Heights student residence was reserved for black students – a Bantustan in a democratic South Africa.

We assumed, quite rightly, that this was a symptom of a system of structural domination in which we were the unwilling cogs, a manufactured underclass in perpetual service to a callous upper class despite our freedom. Still, we dreamt the dreams of our heroes – of a nonracial, nonsexist society in which we could live with the promise of equality.

We still dream, but the innocence of the promise of freedom is lost. Our former heroes have become potential adversaries, our former enemies likely allies.

As the fissures begin to show between the political class and the marginalised underclass, can we attest to a common, lived experience of the symbolic violence of the structural domination that defines class and race relations in South Africa?

While the violence and inequality stem from structural racial domination, further away at the margins this domination seems to express itself in the power play between those with relative privilege and those with none, regardless of race.

In my student days, we devoured Frantz Fanon and Steve Biko just as we read Michel Foucault and Pierre Bourdieu. We were as enamoured with Dumile Feni’s art as with Claude Debussy’s work.

We lived between the urban, the township and the rural – multiple realities at once. Some of us still do. These realities are forever shifting; at times, they appear not to be as black and white as one would like them to be.

Publications

Publications

Partners

Partners