Kenyan film maker Wanuri Kahiu burst on to the scene in 2008 with her moving feature on terrorism, From a Whisper. She went on to become a poster girl for Afrofuturism with her sci-fi short film Pumzi. And now her much-lauded, joyful lesbian love story Rafiki screened unbanned for seven days in her home country, making it eligible for the Oscars. Grethe Kemp speaks to the writer and director about being an African film maker in the spotlight.

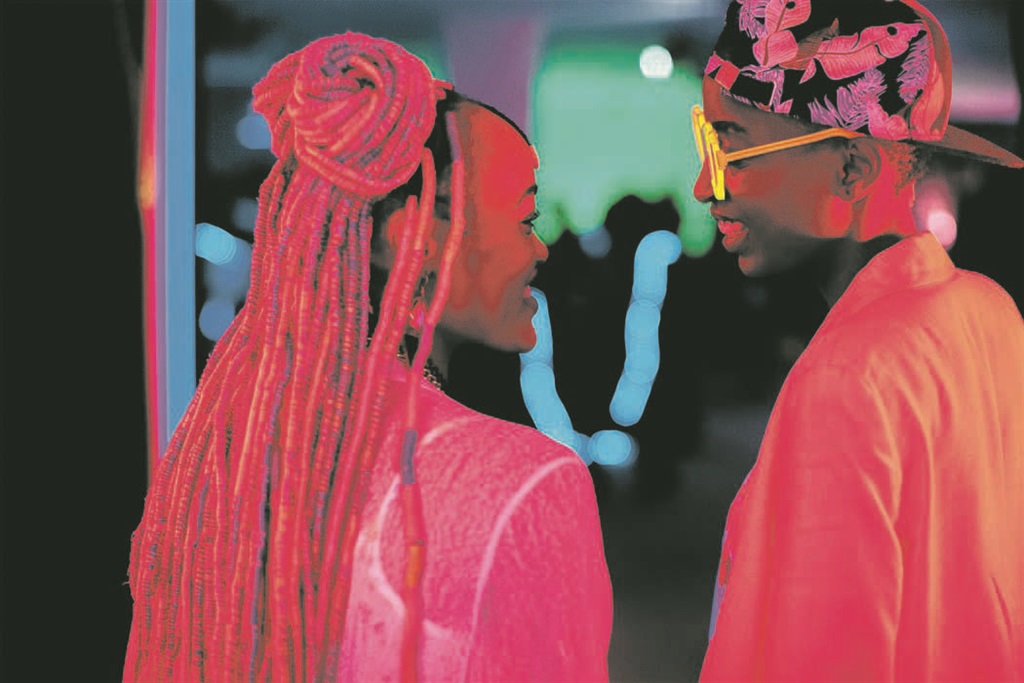

It was the first Kenyan feature film to premiere at the Cannes Film Festival and received messages of support from the likes of Lupita Nyong’o and Kerry Washington. But Rafiki – about two girls who fall in love – was not allowed to be seen at home.

Banned in April this year by the Kenya Film Classification Board “due to its homosexual theme and clear intent to promote lesbianism in Kenya, contrary to the law”, the film was temporarily unbanned last week, with much applause from Kenya’s LGBTI community. Gay sex is still illegal in the east African country. It also became the second-highest grossing film in the history of Kenya, despite only running for seven days.

Not only has Kenya now been able to watch it freely, but the week-long run was intended to allow the film to be eligible for a Best Foreign Language Film nomination at the Oscars, with a decent shot at a shortlisting.

Wanuri Kahiu, the director of Rafiki, already has six films under her belt and has quickly become the “it girl” in terms of African film making today. We spoke to her this week:

With Pumzi, you sort of became the poster girl for Afrofuturism. Did you feel any pressure around that?

To be honest, no. *She laughs* I wouldn’t know who to feel the pressure from because I need to be able to speak through my creations. The difficulty is trying to find a way to get the films out there.

What has it been like having Kenyans flock to cinemas to go see Rafiki?

We were super grateful for it because all we wanted was for the film to be shown in Kenya. We were just so amazed that audiences came and that they were appreciative of the work. I think they just enjoyed the work, which was extraordinary because that’s all that we wanted.

Tell me about getting Rafiki unbanned.

Myself and an organisation called the Creative Economy Working Group went to court to get the ban lifted because we felt it was a right within our Constitution for people to be able to see it. We’re actually still in court fighting a larger case for freedom of expression.

Nairobi has long been a hub to tech, design, fashion, music, film and ideas. Why do you think so much is happening there?

I think we’re naturally curious and adventurous when it comes to exploring ideas and new ways of looking at life. Also we have really great access to the internet, which I have to say is a huge thing; it’s affordable and it’s fast, so we’re able to keep up with what’s happening in other parts of the world. But also we’re able to participate quite quickly in things that we believe in and ideas that we have. That makes us innovators in many spaces. We have quite a few innovations happening on our side, like M-Pesa [a groundbreaking phone-based money transfer, financing and microfinance service], which really push us into a new way of thinking and working with tech.

Did you have public support from Kenyans during the court case?

It’s hard to tell. I think we can only tell by the number of people who were anxious to watch it and turned out in droves to do so. But the court case happened so quickly. We were pushing for the film to be seen before the end of November and then it happened last week.

In South Africa we had a similar case with gay Xhosa initiation film Inxeba, where our film and publication board tried to get screenings limited by giving it an X rating, but where especially young people were pushing for the film to be shown everywhere. Do you think there’s a radical disconnection in Africa between what the youth want to see and what the powers that be think they should be allowed to see?

I don’t think it’s just the youth, I spoke to people who were much older and were uncomfortable with the state deciding what they should watch. It was this very paternalistic view from the publication board of how they decided. A significant number of people felt that it wasn’t government’s space to decide.

Do you ever feel that you’re called to speak on behalf of a big group of people, for example, on behalf of African film makers or on behalf of black women film makers?

I genuinely just speak on behalf of myself. I think there are enough people who resonate with what I’m saying. Those who it speaks to understand the meaning of the importance of representation and of joy and hope in the work. Those are the people I speak to or for – people who understand that the most important thing for me is to create a joyful happy vision of Africa.

Do you currently feel joy and hope around African film making?

Absolutely, I think we’re fighting for our rights because we believe in our Constitution and we believe in freedom of expression. I don’t think we would’ve taken the course we did if we hadn’t had hope that we could win.

Do you almost feel like a pioneer in that fighting this legal battle will make it better for film makers?

I’m just trying to work and make sure that everybody else’s right to work is respected. I don’t feel like a pioneer, I feel like I’m trying to work, and I’m trying to fight for my rights and others’ right to work. As artists our work is to express ourselves and our work is to impart ideas and we have the right to do that, and all I want to do is to advocate the right to do that. I don’t know if that’s pioneering, it’s something that’s deeply personal and deeply personal to other artists as well.

There’s been a lot of work around the normalisation of romance between same sex couples. Tell me about how you approached the filming of intimacy in Rafiki.

The film was a reflection of what the characters were going through. Because they had such an innocence about them and because they were new at being in love with someone we approached any intimacy with them in the same way. We wanted to show them young, fumbling and figuring it out.

Where do you see yourself in relation to figures like Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie and NoViolet Bulawayo?

I’m always inspired by women who are creating stories out in the world, especially women from the African continent. Because I know the struggle, and I know what it’s like to be a woman in this time of patriarchy, working to have a voice and to release your work, I’m deeply impressed and influenced by their work always. I’m also excited about it, I follow it so closely, I’m excited by what they say and how they say it because it always feeds my spirit.

You’ll be coming to South Africa in February next year to be a speaker at the Design Indaba Conference 2019. What will you be talking about?

Afrobubblegum, always.

Wanuri explained Afrobubblegum in a TED talk recently, her movement that is African, vibrant, lighthearted and without a political agenda. She told Design Indaba: “My work is about Nairobi pop bands that want to go to space or about seven-foot-tall robots that fall in love. It’s nothing incredibly important. It’s just fun, fierce and frivolous, as frivolous as bubblegum.

“So I’m not saying that agenda art isn’t important; I’m the chairperson of a charity that deals with films and theatre works about HIV and radicalisation and female genital mutilation. It’s vital and important art, but it cannot be the only art that comes out of the continent. We have to tell more stories that are vibrant. The danger of the single story is still being realised.”

- Rafiki is screening at the Cape Town International Film Market and Festival on October 11 and 15. Tickets at filmfestival.capetown/festival/

- Tickets for Design Indaba are already on sale at webtickets.co.za

Publications

Publications

Partners

Partners