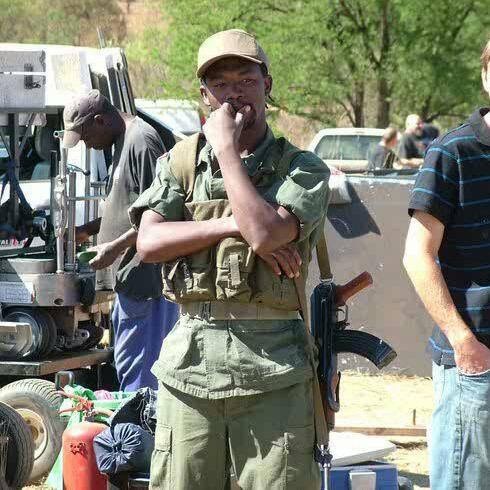

In 2013, stuntman Bongani ‘Champion’ Zulu was run over by a Casspir vehicle while working on a movie set. He was hurt so badly that he almost died and will not be able to work again. Accidents like these raise questions about whether those in the SA film industry are properly protected. Grethe Kemp investigates.

It’s a grey afternoon in August when I meet up with Bongani “Champion” Zulu and his wife Cynthia at a restaurant in Germiston. I’m here to hear the story of an accident that took his career and his health, evidence of which is written in the deep scars visible above the collar of his shirt.

Zulu started out as a stuntman in 2006 and trained on the set of action film Blood Diamond. He freelanced for various stunt companies on sets across the country and, with Cynthia’s wages as an employee at Wimpy, they supported their two children as well as his mom.

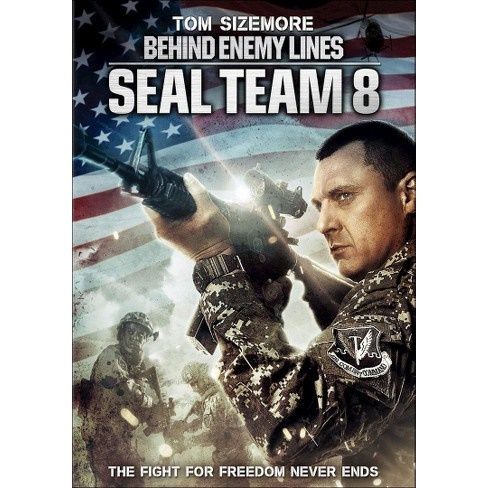

But on June 3 2013, a horrific accident on a film set at the Hennops River near Kempton Park for a US action movie called Seal Team 8: Behind Enemy Lines changed everything.

“We had rehearsed the stunt I was supposed to perform two days before the actual shooting. The scene involved a lot of action, fire and bullet hits. But when the filming began, everything we rehearsed changed,” a reserved Zulu tells me as we place our orders.

The scene involved a Casspir army vehicle – the type the South African military uses.

“The driver who was supposed to drive the Casspir was supposed to be a stunt driver. But it ended up being the owner of the Casspir, not a stunt driver. To my knowledge, the driver didn’t have any information about that scene. I was one of two stuntmen. I was the first to go in front, carrying a rifle. When the battle starts, I am the first to get ‘shot.’ I did as I had rehearsed – taking two hits and then going down. There were some bushes there and I lay in them, waiting for the scene to end. The driver in the Casspir was supposed to turn, but went straight instead and drove over me.”

The Casspir’s right-hand tyres rammed over Zulu’s upper body.

“I remember standing up, taking three steps. Blood was flowing out of my eyes, mouth, nose and ears. The scene was still going, so there was a lot of noise and not many people noticed what had happened. I tried to shout for help, but no sound was coming out. I was just trying to breathe and then I collapsed. I woke up in hospital after a few days in a coma.”

According to a report by specialist surgeon KC Kozaczynski of Fourways Hospital, Zulu sustained injuries including neck, chest and abdominal trauma, a fractured right wrist, multiple rib fractures on the left and right, a collapsed lung, multiple spinal fractures, cardiac contusion and a fractured right shoulder blade.

Zulu had to be intubated (where a tube is put into one’s trachea to provide the body with oxygen) and was put on a ventilator for 17 days.

Cynthia has a soft voice, but is fiery when she talks about that day and her struggle to find out what was going on. She was pregnant with their third child.

“They didn’t phone me when it happened. I had knocked off from my job at Wimpy and called his phone. I was at the shops and wanted to know which takkies he wanted as he needed new ones. When I called, another guy answered and said he was Champ’s boss. I kept saying: ‘Where is the owner of the phone, I need to speak to the owner of the phone.’ I kept asking him who he was and he wouldn’t tell me. I hung up and phoned back 30 minutes later. When I phoned again, I heard sirens in the background, and the guy said that Champion had been in an accident and they were trying to locate his family.”

Cynthia says she feared he was dead.

“I am a gifted person and I remember telling my colleagues I had dreamt of Champion going into a taxi. In African culture, if you dream of someone going into a car, it means that person is going to pass away. I called one of my colleagues and told them that I was at the mall and related what had just happened. When I saw Champion, he was on a ventilator to help him breathe. The nurse told me that, without it, he would die.”

Fair payout?

After weeks in hospital, Zulu was released, but his body was shattered. Zulu’s lawyers negotiated a settlement for him, which the family accepted.

He says: “At first, they offered me R500 000. I refused until my lawyer called me again and said that was the offer they were saying I must receive. For him, it was a big amount of money. He said a person who worked for the municipality ... even when they retired, they wouldn’t get that kind of money. I was not working during that time and was just sitting at home. My wife was pregnant and these circumstances forced me to take that money.”

Zulu was employed as a stuntman by a company called Kleeva Kleen, which was then subcontracted by Pyranha Stunts. Pyranha Stunts was contracted by Film Afrika Worldwide, the production company for Seal Team 8.

The settlement amounted to R1 030 800 – R250 000 had already been paid by accident policy KEU to Film Afrika, which they used for Zulu’s medical bills, and 25% went to lawyer’s fees. Zulu’s final payout was R500 000.

Zulu’s settlement, which he signed, absolved all parties of any further financial responsibility.

A lawyer #Trending spoke to says that, although the settlement may appear to be low, it was probably based on a variety of factors, including how much Zulu had worked during the year and what his loss of income was.

Either way, much of the money Zulu received was used to pay for his countless medical bills and, after building his mother a house and supporting his family for years, the money is now gone. Because of his injuries, he can’t legally work on film sets again because they won’t be able to insure him.

Cynthia quit her job because she needed to take care of him, so both of them are now out of work.

The couple’s financial situation is dire, and they feel they have still not been told the full truth about what happened on set that day and why.

Cynthia alleges that Zulu didn’t even have a contract while he was working on that film.

“They only drafted a contract for him after the accident. The movie’s fixer would come to visit him, asking for Champion’s address and ID number. I told him I wouldn’t give the information to him. He eventually got those details from Champion’s mother.”

Zulu adds: “Even if they have a contract now, it doesn’t have my signature on it.”

Zulu even tried to claim compensation from the Road Accident Fund, but says that a statement about the accident wasn’t even filed with the police. He claims no one would give him the name of the man who was driving the Casspir, nor the vehicle’s registration number because “it is the state’s car and doesn’t belong to anyone”.

“I was told the person driving the truck was from overseas and they don’t know anything about him,”

says Zulu.

They have also tried to access the camera footage of the day, but to no avail.

#Trending reached out to Film Studios Afrika, asking it about the decision to change the driver, whether Zulu received proper rehearsal time and whether they had properly insured him as a stuntman.

We were told that “due process was followed and insurance benefits settled”, and that they would “refer all further communication from you to the legal team involved at the time”.

Underprotected

Accidents like Zulu’s highlight a continuing problem in the South African film industry. Adrian Galley is an actor and the vice-chair of the SA Guild of Actors, a professional guild that lobbies for global best practices in the local industry. He says that actors and film crew don’t enjoy the protection that they should.

“South African actors are vulnerable to exploitation and their working conditions are completely unregulated. One of the main reasons for this is that, being freelancers, actors are mostly seen as ‘independent contractors’ and, as such, are specifically excluded from the protection of the Basic Conditions of Employment Act and the Labour Relations Act. What’s more, actors’ uncertain status in law sees them prejudiced by the Income Tax Act, and the Unemployment Insurance Fund and Contributions Act. Even the Occupational Health and Safety Act excludes actors from meaningful participation in matters of workplace safety,” Galley says.

A big problem is that there is no union for people who work in the film industry.

“Because actors are ‘serially unemployed’ and there are no ‘employer bodies’ in the entertainment sector, they cannot register a labour union,” Galley says.

This lack of a union adds to the exploitation of actors and crew members.

“Because of their status as independent contractors, the wellbeing of cast and crew is not protected through any regulations. Production companies work along generally accepted guidelines, but there are no statutory obligations limiting working hours and overtime, for example. Local producers go so far as to use this as a ‘selling point’ when enticing foreign work to our shores.”

Zulu says that stunt people are generally not treated equally on film sets: “We usually have to eat separately from everyone else. There are also divisions between white and black stuntmen, as well as between stuntmen from Cape Town and Johannesburg. I’ve seen a coloured stuntman get painted black to do stunts as a black character.”

He alleges that the advanced stunts that pay more are usually given to white or coloured stunt performers.

“There are a lot of black people with the same experience, but they don’t get the jobs. All the black stunt guys from Joburg are the best – they’ve worked on films like Casino Royale. But they won’t allow us to do those things.”

Cynthia feels that the low media exposure around Zulu’s incident has a racist component to it.

“Recently, a stuntwoman lost her arm and it got so much attention. Was it because she was white? No one even heard about Champ’s accident.”

Olivia Jackson lost her arm in 2015 when she crashed a motorcycle into a metal camera arm during a film shoot in South Africa. Olivia spent 17 days in a coma following the accident, in which she also suffered a broken shoulder blade, ribs and vertebrae, as well as bleeding on her brain.

A board called the SA Stunt Association has been established. It is trying to streamline communication between film production teams and stuntpeople, but it is still in its infancy.

Though the creation of bodies like the SA Guild of Actors and the SA Stunt Association will mean an improvement in the industry, this comes too late for people like Zulu.

“He can’t even pick up his youngest son,” says Cynthia. “They took away our lives.”

It was the afternoon of April 12, the light was threatening to fade and shooting on the set of the thriller Outsidewas rushed and stressed. It had been raining for days and the schedule was slipping. A climactic fight scene had been set up on some rocks, ominously close to the edge of the Sterkspruit Waterfall in the Drakensberg.

As the hero and baddie began a take on the fight scene, leading man Odwa Shweni lost his balance and slipped into the fast-flowing water of the Sterkspruit River. Within moments he had washed over the edge of the waterfall. His body was recovered by divers the following day.

Aside from a mat placed on the rocks where the fight was to be filmed, there were no requisite safety measures in place according to numerous cast and crew interviewed by City Press in an investigation aided by the SA Guild of Actors (Saga), a report of which was published a month after Shweni’s tragic death.

“No stunt professional, no safety officer, no nets, no cheat shots, just some mats ... It was a cowboy operation ...” said one of several witnesses interviewed by City Press.

First-time feature director and co-producer Sipho Singiswa, who created the film with co-producer and writer Gillian Schutte, denied the cast and crew’s claims vehemently, calling them “absurd and either grossly exaggerated or devoid of truth” and threatened to take legal action for defamation.

But documents, photos and emails appeared to back the allegations that Shweni was the victim of gross negligence and broken promises on the part of the producers.

More than six months after the fall there is still no closure for the widow and family of Shweni. They have appealed to the police and the National Prosecuting Authority (NPA) to conclude their investigation and make a decision on whether the film makers will be charged and prosecuted. They paid for a private autopsy to speed up the process. Family spokesperson Sncedile Shweni this week told City Press there was no update on the case, and the long wait continues.

NPA spokesperson Natasha Kara offered the same response as when asked previously by City Press for an update: “The matter was referred for an inquest and we are still awaiting the findings.”

According to police sources working on the matter, the docket has been up and down between the police and the prosecutors, but there is still no inquest finding.

The autopsy revealed that Shweni did, in fact, die from injuries sustained from falling over the edge of the waterfall near Monk’s Cowl in Winterton.

Although the film makers appear to have failed to secure a permit for the shoot, there are not many laws that govern film shoots even though there is a clear set of guidelines for actors’ safety.

They could face charges of culpable homicide if the matter is criminally pursued by the state, say legal experts.

Outside, which is incomplete, is a violent political horror movie in which a fictional Singiswa, Schutte and their son go on a camping weekend to get away from the internet trolls hounding Schutte’s character after she outed a judge as racist.

In real life, Schutte was behind the fall of Judge Mabel Jansen, whose comments on black men and rape angered many.

Saga has put out repeated statements about actors’ safety in an industry that needs tighter regulation and stronger support for freelancers. While most producers stick to stringent safety rules, many smaller outfits making films on low budgets are guilty, according to actors interviewed by City Press, of letting the rules slip – with potentially fatal consequences.

Read the full investigation at city-press.news24.com, titled What killed Odwa Shweni?

Publications

Publications

Partners

Partners