Garreth van Niekerk meets some of the people behind a countrywide cultural project to restore the memory of Khoisan people and their indigenous heritage

Khoisan elder Chief Elwin White just called to say: “Sorry. I took the wrong BRT [Bus Rapid Transit System]. Be there in 20.”

I don’t know if I was expecting him – a chief of what was once “the largest population” on the planet – to be on time, but I certainly wasn’t expecting him to say he had taken the wrong inner-city bus link. Either way, with 20 minutes to kill, historian John Wright and I get a head start on our walk through On the Trail of Qing and Orpen: From the Colonial Era to the Present, Standard Bank Gallery’s permanent exhibition for 2016 and the reason the three of us are coming together today.

As professor emeritus of history at the University of KwaZulu-Natal and the author of rock-art books including Bushman Raiders of the Drakensberg 1840-1870, you couldn’t ask for a better partner than Wright to walk through an exhibition like this. His wealth of knowledge is immense and invaluable.

The exhibit, which he helped curate, in essence considers the relationship between history and the archive by unpacking an infamous article that Qing, a 19th-century “Bushman”, and Irish-born Joseph Orpen, a colonial administrator, seemingly authored together in 1874. The article they wrote has become a primary resource for anyone investigating indigenous cultural production from that period, but remains a contentious piece

of work.

At the entrance of the show, there’s a glass case of suspended wooden bows – pretty standard natural history museum fare.

“The problem is that it’s all culture and no history,” Wright tells me, looking at the case of arrows, “but the Bushmen are more than just bows and arrows. Part of the job of this exhibition is to see the Bushmen as historical agents, not just cultural agents. That means in the end as political agents as well, not just victims of history, but people who can make their own pasts and write their own stories.”

The disparity between the history of an object and the cultural meaning it has collected over centuries creates a tangible tension throughout the exhibition, asking what the archive of knowledge about the Khoisan does to maintain their memory in the collective imagination.

“This is not an engraving, not just a pretty Bushman picture,” Wright explains in front of a rock engraving of an eland.

“The past becomes hugely important in discovering your identity in the present, but if you’re only seen as a cultural agent, that positions you only in tribal culture and everything in your head is your tribe. You’re not an agent, you’re not a doer, you’re just an actor-outer of your tribal culture. History has the potential to position you as a political agent with the power to structure the politics of your own life, oppose, resist, go along with and make alliances.”

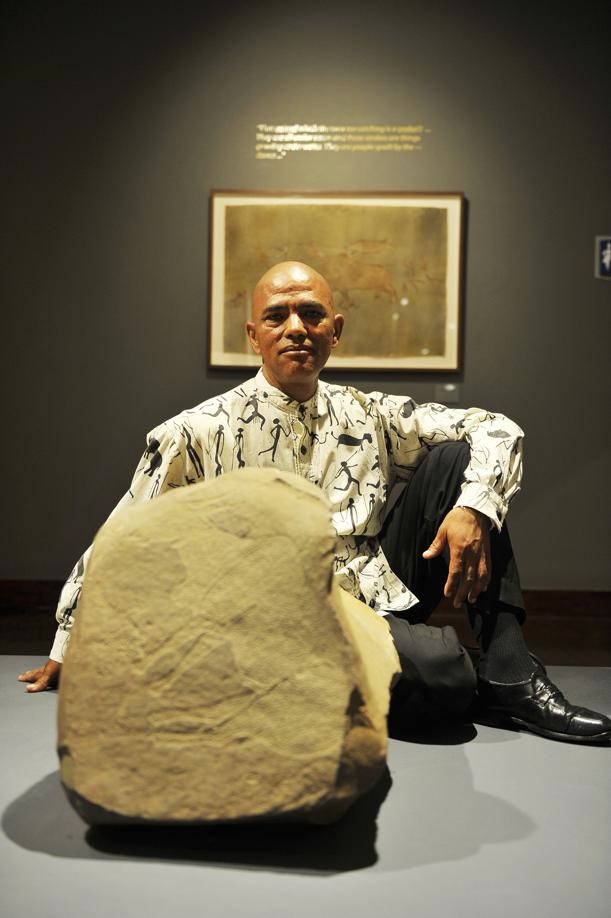

A few minutes later, Chief Elwin White arrives. City Press photographer Elizabeth Sejake and I were keeping our eyes open for a man in “tribal regalia” as discussed on the phone, both of us anticipating a great opportunity to get the perfect photograph for our story, but he’s wearing a Madiba-style shirt that has rock-art figures printed on it.

Clearly, our misguided assumptions of a Khoisan chief still linger, something White is totally aware of. After a few photos and a tense interaction with Wright, we start talking about the exhibition, and the chief is not happy – not at all.

“They are making money out of our pain in this exhibition,” White says. “It is a tragedy to come and see it. I feel my ancestors present in this process when I look at all this, and I can feel that my ancestors are angry. They died brutally, they were killed brutally and yet now, today still, not a single cent goes back into the development of the Khoisan.

“Let us be part of the decision making of this process is all we ask. Let us share in this process with them and work towards the development of the Khoisan and then they can continue making all these exhibitions about us.”

His frustration is palpable. He blames me, the closest representative of a “corrupt” media industry to him at this moment, and the ANC government for the state of Khoisan affairs.

Says Wright: “We white academics face this all the time. You know, ‘Who are you, to write our history?’ Well it’s fairly easy to answer. I am writing my own history, the history of my society. It’s not your history, you can go and write a history of your own history.

Says White: “You know you whites are known to be settlers here in our country, but it’s time the blacks understand that they too are settlers. We have had enough of how we are being treated by them 22 years after apartheid and are now ready to fight to get back our rights.”

The conversation predictably goes to the controversial Traditional Leadership Bill, the recent UN conference and resolution on the inalienable rights of indigenous peoples and then, as everyone in South Africa knows, the debate around what claim to land the Khoisan people are constitutionally afforded.

For hours, we have an extremely

honest conversation that ends with us parting ways with very little left to

say to one another.

I feel helpless and White looks deflated.

The struggle of the Khoisan people feels like one of the last of the apartheid constitutional structures that need to fall.

The result is an increasingly violent Khoisan struggle that has never been more visible than it is now. One of the most publicised recent incidents saw the burning arrows of kings, queens and chiefs of the Khoisan royal houses soaring through the sky into the grounds of Parliament when they marched on the building, demanding to be recognised constitutionally as the indigenous people of South Africa – they are currently classified as traditional people.

It’s in the Cape that they are most vocal in their campaigns for equality. I joined a group of young and old Khoisan at the Castle of Good Hope on International Mother Language Day last month to participate in one of their lighter moments of community upliftment and awareness.

“When Europeans came here, this place wasn’t called Cape Town yet,” Bradley van Sitters of the Khoi and San Active Awareness Group tells everyone who is gathered together in one of the former slave chambers.

“This place was called another name by the local inhabitants – ||Hui !Gaeb. Everyone, say it with me: ‘||Hui !Gaeb.’”

Everyone tries to say it, the initial clicks sounding like when you say tsk! tsk! in English. “Okay, this side you say ||Hui.” One half of the room shouts “||Hui” in unison. “And this half of the room, you say !Gaeb.” And so they say “!Gaeb”.

“The work we are trying to do is to bring into popular memory the real name for this place. It’s important that we know it because it came a very long way to get here,” Van Sitters says.

Every Saturday, he leads free Nama, or more officially Khoekhoe, lessons at the castle for a small but dedicated group of people – some Khoi, and some people just interested in the language. Nama is one of the few remaining Khoisan languages that are in use today. About 200 000 people still use it in Namibia, where it is an official national language and is taught in universities and schools.

As one attendant reminds me outside the workshop, if you take any South African coin from your pocket and flip it on its head, you will find, beneath the two San figures that grasp hands in the coat of arms, a short sentence written in fine text that reads “|ke e: ||xarra ?//ke”. The phrase translates as “diverse people unite” in the now-extinct Xam language – one of the more than 2 000 extinct or endangered Khoi languages and dialects which, despite this grandiose iconographic gesture, are not recognised as part of South Africa’s 11 official languages.

The exclusion of the Khoi languages, which linguistic archaeologists trace back to the beginnings of language itself, is just one in a long list of historical segregations that affect the visibility of the Khoisan.

In a promise of provisions during his state of the nation address in 2012, President Jacob Zuma said: “It’s important to remember that the Khoisan people were the most brutalised by colonialists who tried to make them extinct, and undermined their language and identity. We cannot ignore to correct the past.”

One of the best-known tragedies resulting from the consequences of ignoring vulnerable groups like the Khoisan is finally being immortalised, some 200 years after the fact. In Hankey in the Eastern Cape, where Sarah “Saartjie” Baartman, the “Hottentot Venus”, was finally laid to rest. Since 2012, the department of arts and culture has quietly been leading a multimillion-rand project to memorialise the site of her burial atop a hill overlooking the Gamtoos River Valley, unofficially known as the Sarah Baartman Centre of Remembrance.

The centre was designed by Wilkinson Architects and will include a museum dedicated to the Khoisan – the first of its kind in the country. A Genocide Wall will be a central feature of the design, in the hopes that it will “help educate the visitor on the experiences of the Khoisan people”, the architects say on their website.

“The history of Sarah Baartman is fraught with contestation, and none more so than her place in the historical archive of South Africa,” Lisa Combrinck, a spokesperson for the department of arts and culture, told #Trending this week.

“She is at once icon, historical entity and Khoi woman who underwent many hardships in Europe under colonialism. For many South Africans, the name Sarah Baartman became known when her remains were interred in Hankey in the Eastern Cape, after years of being kept as an object in a French museum.

“But the history of Sarah Baartman, and her personal journey from South Africa to England and then to France, has been known by the Griekwa and Khoi peoples of South Africa for longer than that. The return of Sarah Baartman and her burial on South African soil is an important moment in South African and Khoi, San, Griekwa and Nama history. Culturally, it has reclaimed her identity and humanity as a person.”

These cultural interventions are only a fraction of what should have been done by now, but they are at least offering hope to generations of displaced Khoisan people who find themselves almost without a place in history.

The thing with recapturing histories, as author Richard Lee points out in his identity politics work, is that it’s not simply a question of reviving old ethnicities. It is also about acknowledging the birth of new ones and, for the next generation of Khoisan people, this might make all the difference.

. On the Trail of Qing and Orpen: From the Colonial Era to the Present is on at the Standard Bank Gallery in Johannesburg until December 3, Monday to Friday, from 8am to 4.30pm, and on Saturdays from 9am to 1pm

. Free Nama language lessons take place at the Castle of Good Hope in Cape Town every Saturday morning. For more information, contact Bradley van Sitters at ksaag@gmail.com

Publications

Publications

Partners

Partners