It wasn’t Ayanda Mabulu’s sensationalist painting of Nelson Mandela depicted as a Nazi that grabbed international headlines at last week’s FNB Joburg Art Fair, but an altogether different kind of work.

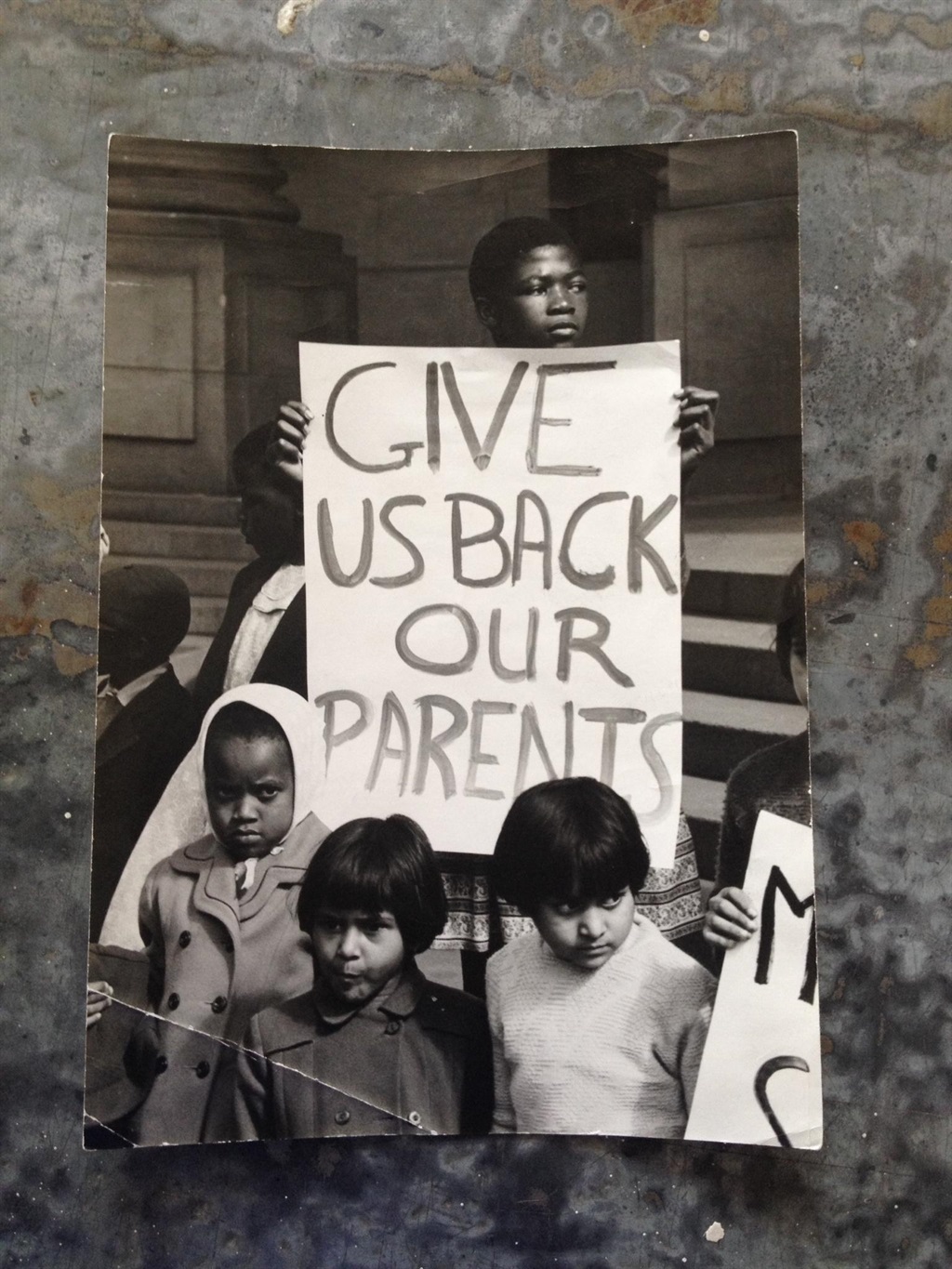

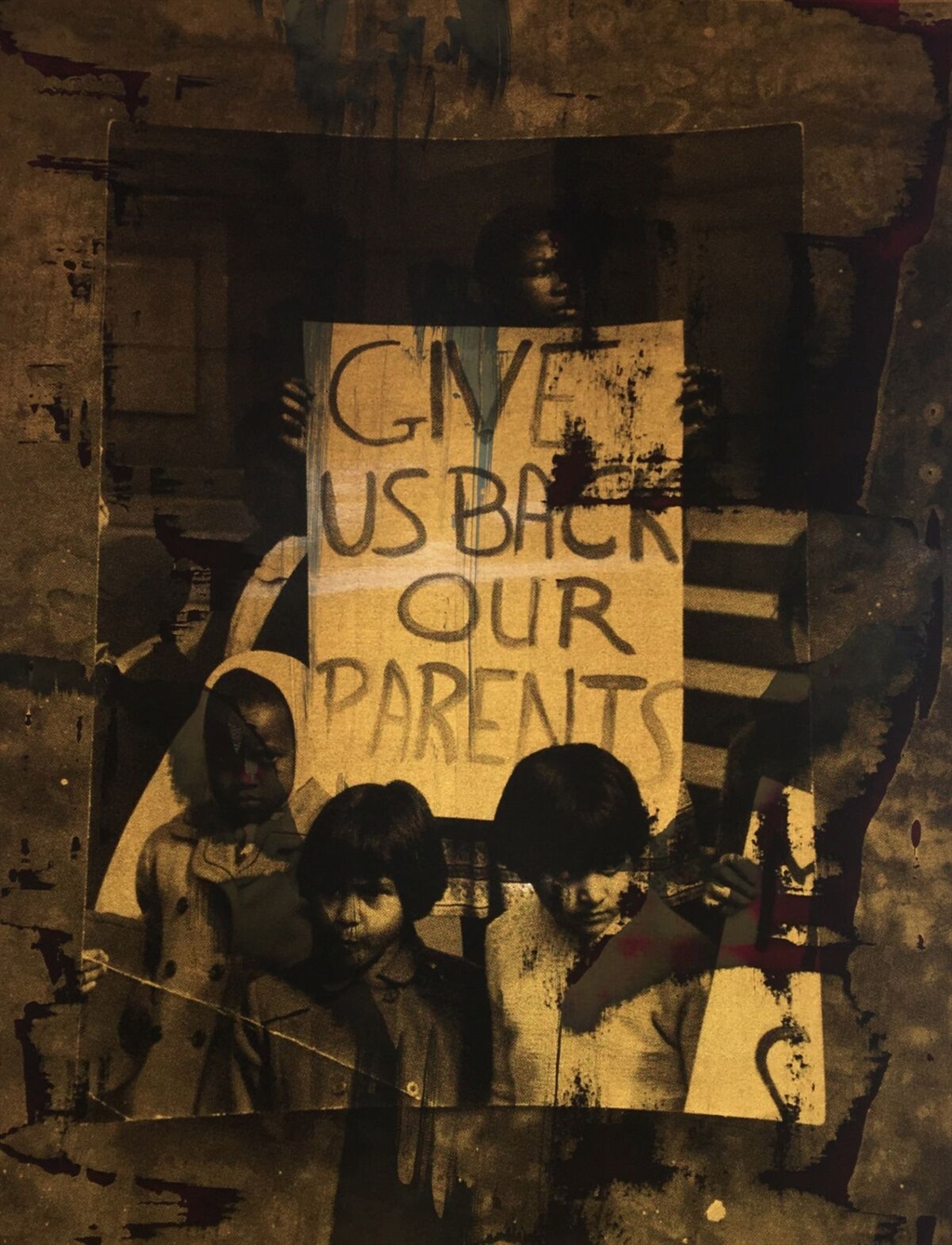

Veteran South African photographer Graeme Williams has told City Press how he was looking through the gallery stands at the VIP opening night of the Joburg Art Fair when he came across a new version of his most famous photograph by celebrated African-American conceptual artist Hank Willis Thomas called Gravitas in the Goodman Gallery space.

Williams says he never gave permission for Thomas to use his work and accused him of plagiarism.

Thomas has defended his work in an interview with City Press this week.

It's not the first time work has been contested on the fair. Last year, work on the ROOM Gallery & Projects display – notably Ubuzwe 1 by Sikhumbuzo Makandula – has also led to accusations of copyright infringement and exploitation by visual and graffiti artist Buntu Fihla.

City Press spoke with the artists and asked copyright experts for their legal opinions on the two cases.

Case 1: Williams vs Thomas

WHAT WILLIAMS SAYS

Over the phone to City Press Williams spoke out about the “sloppy plagiarism” he encountered whereby Thomas “slightly whitened part of the image and attempted to make it his his own.”

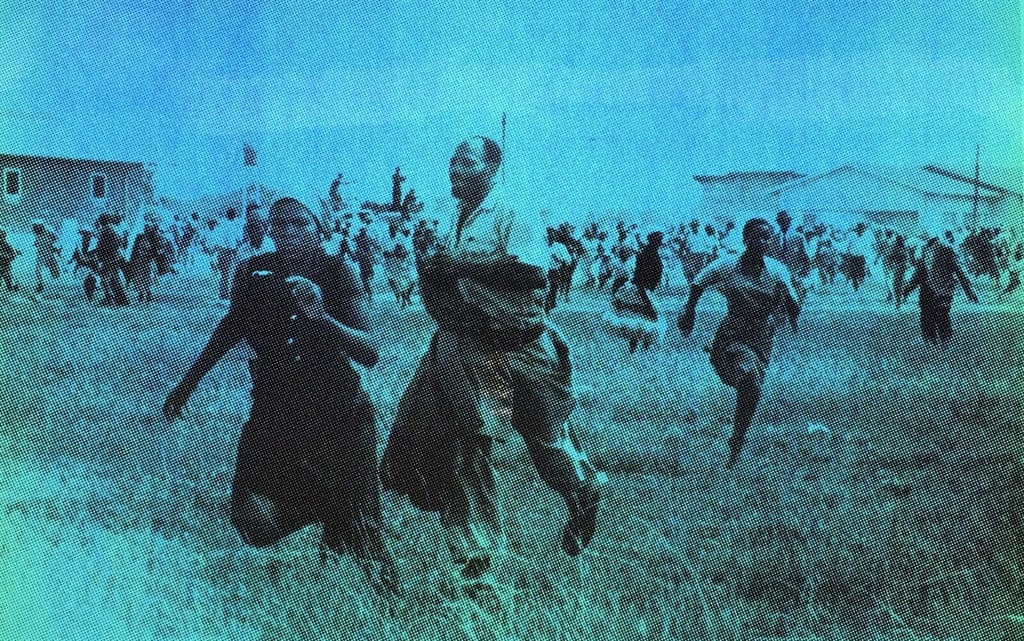

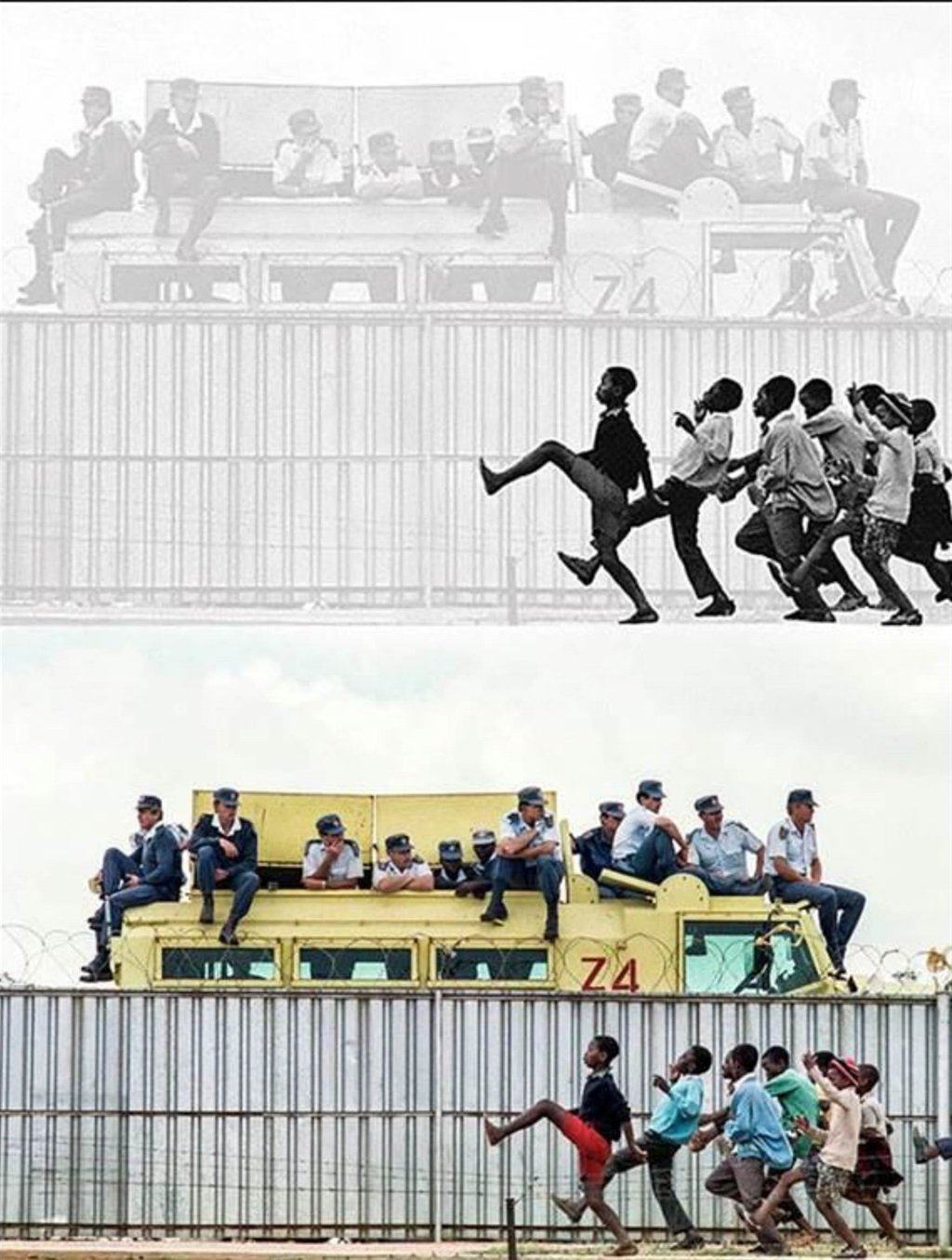

He took the photo in Thokoza in 1990 a few months after Nelson Mandela was released from prison and was holding a rally in Thokoza. The image captures a shift in power, with black children doing a mocking duck walk alongside the police in an armoured vehicle.

Williams says that he immediately asked the Goodman to remove the work from its walls – one of numerous Thomas pieces reworking South Africa’s photographic archive including several Peter Magubane images.

The gallery, he says did not do so until the next day, and later sent him an apology of sorts.

The gallery did not respond to questions from City Press, instead putting us in touch with Thomas and sending us the credits at the art fair stand which acknowledged the creators of the original works that Thomas “transformed”.

The credits were not on the works but in a separate document.

And anyway a credit is not a permission. Williams said no-one asked to use his image, which he sells at about R15 000 a framed print. Goodman was selling Gravitas for over half a million rand.

Thomas’ argument that the work is a sufficiently changed version of the original and hence didn’t need permission is arguably negated by the fact that the whitened out police are visible with a camera flash or if wearing special glasses, making the most significant change the fact that Thomas has presented the colour photo in black and white.

“We understand what the photo is about, all the nuance,” Williams says. “We really don’t need someone from the US pushing alternative readings.” He says he happily gives free use of the image to students for academic purposes and has made relatively little money from selling and licensing the work.

On his Facebook page Williams then wrote of a phone call he received from Thomas: “The artist called me yesterday evening and suggested a solution to ‘this problem’ and a way to stop all the complaining. He offered me his ‘artwork’ and proposed that I keep it in my home for year and we would then reconnect to discuss ‘the problem’ further. Presumably it will take a year for me to fully understand the depth of his creative input and the complexity of the changes that he has made to my image. I declined the offer.”

He told City Press that he felt Thomas was patronising, coming from “a place of arrogance”. He says he asked Thomas to destroy the work, which Thomas said he wouldn’t do and then told him he was “lawyered up, but even if I win the case I won’t feel good about it. I don’t want to be the poster boy for appropriation and plagiarism.”

WHAT THOMAS SAYS

Over the phone from the US on Friday, Thomas told City Press that the only part of Williams’ account he would refute is the bit where he is reported to have said he was “lawyered up”.

“I was saying that lawyers always make it a black and white issue when in fact there are a lot of grey areas. I actually thought [Williams] was very kind and thoughtful. I apologised for aggravating him. Even if we disagree I will defer to him. I told him I won’t destroy it, but he can, he can burn it, he can sell it, but he should hang onto it and see how he feels in a year. I offered to ship it to his gallery.”

Thomas’ work is often a comment on remix culture and capitalist exploitation of black identities.

Ask why he never sought Williams’ permission, he said, “This is not a new issue and it was already made when I realised it was his. I work with archives around the world, in this case mostly with the Baileys [African History] Archives.”

American copyright law makes greater allowance for what is termed free use and according to the principles of fair use Thomas believes, “I’ve altered it enough to make a new work. If he doesn’t agree then that’s a grey area right there. I also think about other grey areas like does the photographer always get permission from the subjects they photograph? Why can I not use an image of people at a public event at a moment that changed history? Who can claim ownership of the people in the image?”

Thomas spoke about work in a digital age, where an image like Williams’ can be spread across the internet without permissions. “I tried to make a work you could only see in person,” he told City Press.

He said he didn’t like being called names and that he was trying to do something new with historical imagery. He said he faces backlash in the US too, but it leads to a larger conversation. “My work is about ideas and stories. He must take the money, take the image, I won’t reproduce it.”

WHAT THE LEGAL EXPERTS SAY

IP lawyer Brian Wimpey:

“Despite Thomas’ contention that the work is new or transformative this is clearly identifiable as Williams’ work, police or not. It is a very simple matter. The fact that Thomas’ work was sufficiently modified to warrant it being called a new work is irrelevant to copyright infringement. A new work may itself attract copyright protection, but at the same time can infringe another copyrighted work which is what Thomas’ work is doing by incorporating Williams’ work. Copyright infringement includes making an ‘adaptation of the original’. Williams can interdict Thomas’ further publicising of his work and threaten him with damages if a South African court has jurisdiction.”

Asked about the fact that the work was made in America and would likely find itself tried in the US, Wimpey said:

“Fair use in the USA is a difficult concept to wrestle with, particularly from a South African perspective. Our fair use exceptions, at least for the moment, are very curtailed. Fair use in the US looks at a number of factors, including whether the ‘new’ work is for commercial gain, is transformative, and so on.

The one case that I know of which dealt with artistic works is Blanch vs Koons, but Koons incorporated a portion of an image from a collage, and changed its perspective completely. Willis might find it difficult to argue ‘fair use’ since he is openly reproducing at least half of the image. Having said that, the term ‘transformative’ is difficult to pin down: the questions is whether the adaptation ‘altered the original with new expression, meaning, or message’. What this means is anybody’s guess, and since US law is based strongly on precedents set by previous cases, it will take a heap of research to determine whether the copy is ‘transformative’.”

Copyright expert Graeme Gilfillan:

“In American law, where this would be tried as the work was made in America, precedent could be provided to prove this is a copyright infringement, but that would be a long and very expensive process.”

Professor Owen Dean, Anton Mostert Chair of Intellectual Property at Stellenbosch University:

“The derivative work by Thomas is an infringement of copyright and the copyist is acting unlawfully. The ‘author’ of the initial work, Williams, is the owner of the copyright subsisting in it unless they have assigned copyright in writing to another. Williams holds the exclusive right to reproduce, or authorise the reproduction, of the work, or any substantial part of it, and to distribute such reproductions. In this instance the derivative work amounts to a reproduction of a substantial part of the copyright work made without authorisation.”

Case 2: Fihla vs Makandula

Buntu Fihla goes by the tag of Bief37 and is known for a body of work but in particular his commentary on the former bantustan of Ciskei.

Working in memorial sites in the bantustans and in the case in point Ntaba kaNdoda in Buffalo City, Fihla depicts the blue crane on the flag of Ciskei debeaked.

The untagged mural is called Inyeke kaSebe/Sebe’s Lip, referencing Lennox Sebe, the first leader of Ciskei.

Sikhumbuzo Makandula, in the indie ROOM Gallery’s stable, was a student at Rhodes University when for his thesis work he documented himself dressed as a Chinese character at Fihla’s murals, both the blue crane work and another featuring ivory rings titled Ukufa kukuqhutywa, impilo kuzenzela. Makandula’s new photographs are now sold commercially.

At the art fair the works were clearly credited as “featuring graffiti work by Buntu Fihla” but Fihla receives no royalty and says he never gave permission for Makandula to use his work in this way. Does the fact that this is untagged public art affect the copyright case?

WHAT ROOM GALLERY SAYS

Communicating over email, ROOM owner Maria Fidel Regueros consulted with Makandula in answering questions from City Press. We asked how the gallery responds to claims that Makandula has unfairly or illegally used Fihla’s IP in order to profit commercially from it?

Regueros replied: “From my perspective terms such as ‘unfairly’ or ‘illegally’ place the entire question in a negative light, omits the contexts of each artist’s practice and implies that no interaction took place between the two. Furthermore the question suggests that no acknowledgment was given by Makandula of the elements by Fihla he interacted with.

“I would like to point out first and foremost that the body of work titled Ubuzwe by Makandula was researched, developed and produced as part of an academic endeavour which culminated in to a graduate show at Rhodes University in 2016. From the onset Fihla’s elements included in some of Makandula’s work have been credited by the artist. The intention of the works produced was originally never commercial in nature. It was during this time that I was subsequently informed an interaction between the artists began.

“From my perspective, the use of public art and interaction with it plays a considerable role in the debates that are instigated around IP.

“The position both the artist and ROOM Gallery & Projects holds is that the overall body of work titled Ubuzwe, consisting of 29 works, was researched by and produced by Makandula, which in turn as a secondary element in three of the artworks interfaced/interacted in its execution with that of public murals by Fihla present on a public site.

“Makandula earned money from the sale of his body of work and has acknowledged the inclusion of elements by Fihla’s murals where they were applicable. As far as I understand Fihla has never requested royalties of Makandula ... I do believe that the discussion regarding royalties is between the artists as it involves the creative process of each ... As far as I am aware the discussion around royalties was never brought up by Fihla and has purely focused on crediting of the murals and their author in the context of captioning.”

She provided an email from Makandula to Fihla to show that Fihla had been approached over these matters and said “Discussions are taking place between the artists.”

WHAT FIHLA SAYS

Also communicating with City Press over email this week, Fihla wrote: “Interaction between the two of us does not rule out being treated unfairly. It is misleading to leave out what happened in this ‘interaction’. I asked for the reproduction of any photographs that show my works to stop immediately. I even stressed to Makandula that my emphasis on crediting my work should not lead him to thinking I agree to its reproduction, this only applied to wherever the work had appeared before. Saying that I was credited from the onset is a blatant lie. As I have said repeatedly, Makandula did not credit my work at Rhodes University.”

Fihla says he would have been open to engaging with another artist’s project and he enjoys collaborating.

“I know without a doubt that Makandula knew of my work before developing his. A former lecturer of his from Rhodes University gave a lecture about my work in Ciskei memorial sites. Makandula was in that lecture. He knew I was the artist. He knew how to contact me, but he chose not to do so, and only began to credit me when ROOM Gallery was alerted. Makandula only ever contacted me after I alerted one of his lecturers at Rhodes University about the appropriation of my work. After this, he responded to my emails, but made sure to blame me for not responding to emails he never sent. He then sent me his catalogue, which briefly mentions me and my art. The same art that is the bedrock of that series.”

He adds: “It is also important to note that I document my work, in film and photography, and sell the photographic prints. If a performance artist performed a piece at the Bree Taxi Rank, would this give another artist the right to perform the same piece? I mean, it was performed in public?”

On the subject of tagging, Fihla wrote: “I did not tag the work in question as I felt that would compromise the final composition of the photographs. I often sign my work but I purposely left out signatures/tags from this particular series because I sign and have certificates of authority for each of the prints.”

WHAT THE LEGAL EXPERTS SAY

IP lawyer Brian Wimpey:

“Copyright in artistic works do not fall into the public domain unless the artists specifically makes it so: It is the artists exclusive right to enforce or not enforce his copyright. Makandula may have been entitled to reproduce Fihla’s work for his thesis in terms of certain exceptions in the Copyright Act, but has absolutely no right to sell them for any amount. In terms of the act, “Copyright in an artistic work vests the exclusive right in the owner (author) to do or to authorise the doing of any of the following acts in the Republic:

• Reproducing the work in any manner or form;

• Publishing the work if it was hitherto unpublished;

• Making an adaptation of the work”

Makandula has made adaptations of the original work without consent.”

Asked if the fact that Fihla’s work was not tagged, Wimpey replied: “The artist does not have to sign or tag his work to claim copyright.”

Copyright expert Graeme Gilfillan:

“South Africa has no freedom of panorama law and so the works are public and he hasn’t tagged them to claim ownership. It may be a moral issue to credit Fihla but in law Fihla is on very shaky ground here.”

Professor Owen Dean, Anton Mostert Chair of Intellectual Property at Stellenbosch University:

“The derivative work by Makandula is an infringement of copyright and the copyist is acting unlawfully. The ‘author’ of the initial work, Fihla, is the owner of the copyright subsisting in it (unless he has assigned copyright in writing) and Fihla holds the exclusive right to reproduce, or authorise the reproduction, of his work, or any substantial part of it, and to distribute such reproductions. In this instance the derivative work amounts to a reproduction of a substantial part of the copyright work made without authorisation.”

* This story has been updated after ROOM Gallery pointed out that Makundula's work was not, in fact, on sale at the FNB Joburg Art Fair 2018. We apologise for the error.

|

| ||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||

Publications

Publications

Partners

Partners