Reverend Billy Graham, one of the best known and most widely respected of the Christian evangelists of the 20th Century, has died at the age of 99. He was one of the first evangelists to exploit the potential of mass communication and reached more people than any other preacher of his time. Millions owe their first steps in the Christian faith to his amazingly simple and compelling messages.

Yet his messages, so winsome and personal, were also sanitised of any engagement with the social and political realities of his world. The personal power and frightening social irrelevance of a Billy Graham sermon was that it could be preached anywhere – Moscow or Minneapolis, Accra or Athens, Panama or Pittsburgh – without changing a word. People in large numbers always streamed out at his invitation to accept Jesus into their hearts but there was no danger that Billy would ever get into the kind of trouble Jesus got into. The Jesus he preached was a privatised saviour, good to save souls but not prepared to challenge systems of oppression and exploitation. When Billy preached in countries with nasty human rights records he made it a rule to remain steadfastly silent about their social and political issues. His mandate, he claimed, was to preach the “plain and simple Gospel.” The problem is there is no such thing. What he really meant was that he would offer only half the Gospel, the half that invited people to face their personal sins without confronting the systems that often did their sinning for them.

And that is why we met.

The occasion was the Congress of Mission & Evangelism held in Durban in March 1973. Sponsored jointly by the South African Council of Churches (SACC) and well-known evangelistic organisation Africa Enterprise (AE), it was a deeply sincere attempt to start a dialogue between the more militant anti-apartheid SACC and their conservative-evangelical opposites who tended, either by their silence or support, to bolster the apartheid status quo. The congress was itself something of a miracle: for the first time ever in apartheid South Africa a multi-racial gathering of some 700 people was housed together in the same hotel, riding together in the same buses and eating at the same tables. For this to happen in 1973, it had taken anxious prayer, massive pressure and private pleas to get approval from some eleven government departments for the race laws to be broken.

For conservative-evangelicals, the big drawcard of the congress was that Billy Graham was coming and would hold his first ever mass rally in South Africa at King’s Park Stadium. With many others I had questioned the wisdom of inviting him – we feared that the hullabaloo around his coming would distract from the real issues that needed thrashing out between Christians with such deep divisions about our witness to our land. SACC leader John Rees confided to me that agreeing to a Billy Graham rally was the price paid to get conservative-evangelicals on board for the congress. If they were going to have to listen to “radicals” like Desmond Tutu and Beyers Naude, then we should have to listen to Billy.

Now that he was coming, a small group of us were determined to engage him about our main concern.

When the great man arrived, there was a hullabaloo indeed, but we managed to get him alone late on the Friday or Saturday evening. I have to admit that we were fairly blunt: “Dr Graham, we are here to tell you that unless you denounce apartheid on Sunday you will be harming the Gospel and it would be better if you went home now.” We referred to other countries with ugly human rights records where he had said nothing: “Maybe the Christians there asked you to be silent,” we said, “but we are asking you to speak out, otherwise your silence will shatter the hopes of black South Africans and give encouragement to an evil system.” Billy was clearly taken aback but he listened courteously and then spent some time explaining why he felt called to preach only the “simple Gospel of salvation.” He assured us that among the people who had been converted at his rallies were those who later did see the need to work for human rights and justice.

“Then why not tell people up front?” we countered. “Offer the whole package, not just the easy half. On Sunday you will be inviting people to confess their sin. Why not declare that in this land the most widespread sin to confess is prejudice – that you can’t follow Jesus and hate your neighbour?”

Our discussion went on for a while and Billy was gracious to the end. He said he would think and pray about our words.

On the Sunday, facing a multi-racial crowd of 45,000 people, Billy preached one of his standard “simple Gospel” sermons to great effect, but with one difference. For the first time ever, he crossed his self-imposed line and made a cautious and oblique reference to our nation’s original sin: “If we don’t become brothers – and become brothers fast – we will destroy ourselves in a worldwide racial conflagration.” He went on hastily to diffuse what might be seen as an attack on South Africans alone: “This is not just a South African problem, this is a world-wide problem … the problem is deeper than the law. The problem is in the human heart. We all need a new heart.”

As hundreds of people streamed forward to make their commitments, I breathed a not very happy prayer to God. This man – who back in North Carolina still opposed inter-racial marriages – had at least said something, but I couldn’t help comparing his timidity on this ultra-safe platform with the forthright challenge to apartheid by people like Tutu and Naude and other lesser-known preachers, who were making sermons at great risk from their pulpits.

That day South Africans got barely more than half the Gospel. It would be up to others to ensure that the other half was also heard.

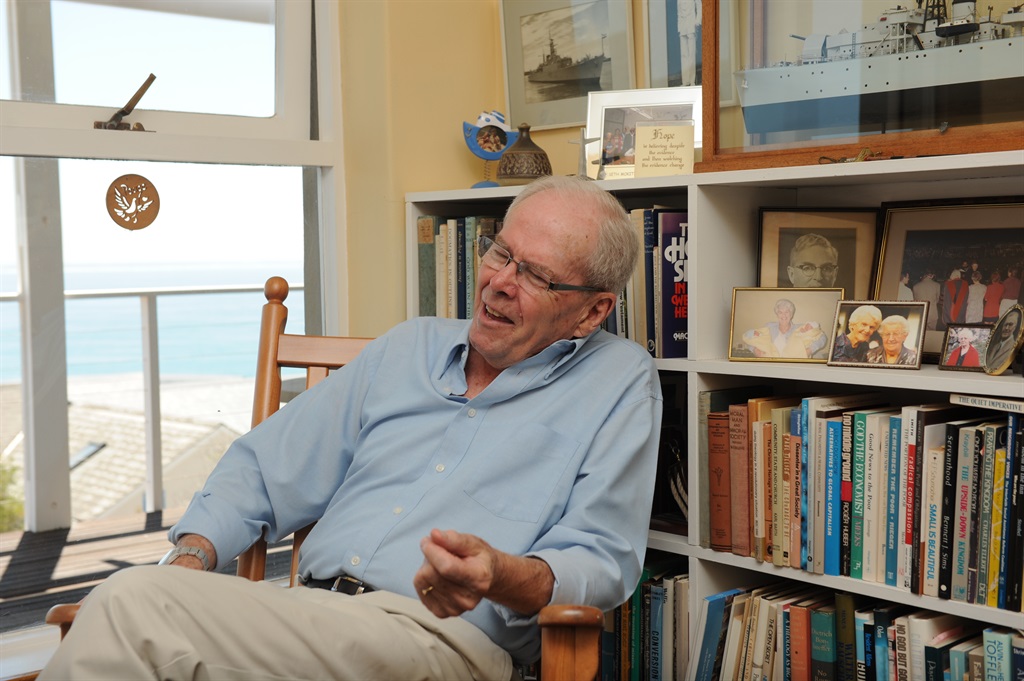

Peter Storey is a former Methodist Church & SA Council of Churches president

Publications

Publications

Partners

Partners