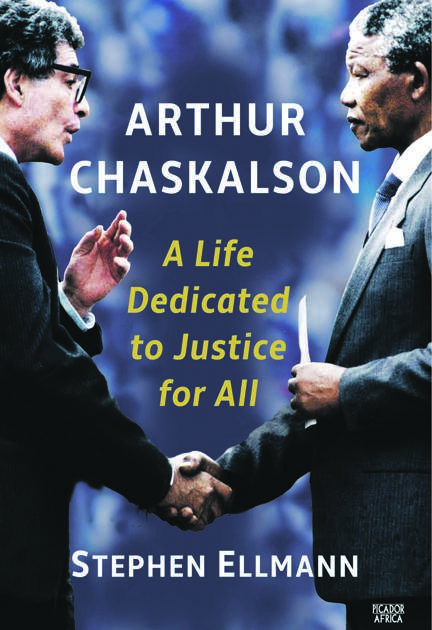

Arthur Chaskalson’s life story and the four phases of his remarkable career – advocate at the Johannesburg Bar; founder and leader of the Legal Resources Centre; his involvement in the Constitution-making process; and his term as the first Chief Justice of South Africa’s Constitutional Court – embody the story of law in the struggle against apartheid and then in a new democracy

Arthur Chaskalson: A Life Dedicated to Justice for All by Stephen Ellmann

Published by Pan Macmillan South Africa

Pages: 864

Price: R550

As the possibility of negotiations with the government loomed, after Nelson Mandela’s release, the ANC faced the task of developing its constitutional proposals.

More generally, the country faced the task of developing its constitutional thinking.

It is not too much of an exaggeration to say that South Africa began an extended constitutional seminar – at the same time that the ANC, the government and other parties carried out an extended, high-stakes political struggle for advantage.

That political struggle was fierce and frightening, and many lives were lost, particularly in clashes involving the ANC and Inkatha [Freedom Party], while strong evidence emerged of a government-sponsored “third force” illicitly bolstering Inkatha’s efforts.

As much as this political struggle turned on sheer political, even military, strength, it rested also on ideas.

Shaping and justifying a constitutional vision for the future was an important aspect of that battle over ideas.

Just as important, those visions potentially would soon become reality, and would govern the new nation now being created.

And more practically, the opposing sides’ constitutional theories intersected with their negotiating positions.

The government favoured a prolonged period of negotiations, in which a more or less complete Constitution could be crafted – and in which, it hoped, the ANC’s popularity, and Mandela’s, would begin to fade.

The ANC, for its part, wanted the drafting of the Constitution to be undertaken by a democratically elected constituent assembly, not only for reasons of democratic principle but also because they were confident of winning such an election; and so they wished the negotiations leading to that election to cover as little ground as possible and to consume as little time as possible.

Arthur himself would describe the two sides’ positions, in a memo he wrote in August 1992:

“The Patriotic Front [the ANC and its allies] saw the primary task of the constituent assembly as being the adoption of a new Constitution. It contemplated that this task would be completed in a comparatively short space of time and that the interim government would be of brief duration.

The legislative structures necessary to provide the framework for the interim government should therefore be no more than was necessary for this purpose.

The National Party contemplated that there would be an indefinite period of interim government and that a detailed interim Constitution should be adopted by Codesa [the Convention for a Democratic SA] which would make provisions for regional government, a consociational legislature and executive, and an interim bill of rights.”

Arthur was not neutral on this clash of approaches.

He had already written, just a few months earlier, that: “It is also crucial that there should be an effective means of escaping from the interim Constitution. The interim Constitution should be a brief stage on the road to democracy, and not a trap which will frustrate the achievement of democracy.”

Just as the resolution of these differences turned in part on the clash of power, it also turned on the interactions of political leaders: FW de Klerk and Mandela, above all, but also their lead negotiators, Roelf Meyer for the government, assisted by Fanie van der Merwe, and Cyril Ramaphosa for the ANC, assisted by Mac Maharaj.

Other political leaders also played important roles: Constand Viljoen, for example, the former defence force general and now leader of the Freedom Front who ultimately decided to bring his followers into the election process, or Mangosuthu Buthelezi, who brought his Inkatha Freedom Party into the election process, too, but only at the very last possible minute.

On the ANC side Thabo Mbeki, the smoothest of diplomats, and Joe Slovo, who in an influential article made the communist case for the wisdom of concessions to win over the other side in the negotiation process, also played important roles.

The politicians’ story is important.

But the part that constitutional thinkers played, applying the judgement of an expert lawyer to the cause of liberation, is important too – indeed, as we will see, very important.

Albie Sachs, in exile, was central to this thinking, in particular to the ANC’s gradual embrace of enforceable human rights.

He was by no means alone in this effort during the exile years – one thinks here of Zola Skweyiya and Kader Asmal, both members, like Sachs, of the ANC’s constitutional committee. When exile ended, Arthur too came to play a very important role.

The ANC took steps to build its constitutional committee.

This committee had first been established by the ANC in the mid-1980s, in the exile years, and was one of several ANC bodies or subcommittees which took an interest in constitutional design.

George Bizos and Arthur were invited to join the committee and accepted.

In fact this invitation came very quickly indeed: on 12 February 1990, three days after his release from prison, Mandela asked Bizos whether he and Arthur “would be prepared to assist him and the ANC with drafting the new democratic Constitution”.

There is no indication that Arthur (or Bizos) ever joined the ANC. (Bizos recounted that when Ramaphosa told him that the ANC had appointed him and Arthur to the legal and constitutional committee, their membership in the ANC was not required.)

But it is quite clear that Arthur threw himself into the ANC’s effort. Arthur confirmed that the condition of his and Bizos’ joining the committee was that they retain their independence.

But he did not hold himself apart from the work of the committee.

He and Bizos went to Lusaka shortly after Mandela’s release from prison and then were incorporated on to the committee; that trip would have left observers in little doubt about his commitment.

I spoke to his close colleague in the negotiations, Valli Moosa, who said that it had never occurred to him to ask Arthur whether he was an ANC member.

Arthur was trusted by everyone on the ANC side, as a person of integrity who had no agenda except to challenge apartheid.

Arthur was never accused of being hoodwinked, or overzealous for agreement – a danger that some on the ANC side deeply feared.

He was, Moosa felt, a part of the freedom struggle though as a lawyer he contributed to that struggle in the way that he could.

He was a trusted comrade, not a trusted lawyer.

Maharaj said, somewhat similarly, that Arthur was never just taken up with the legal issues, but was sensitive to the fact that the Constitution belonged to the ordinary party member or freedom fighter.

He presented his arguments in a very gentle style, but at the same he conveyed his understanding that he was talking to revolutionaries, not lawyers.

This ability to connect with his political clients was not new; it was one of the marks of Arthur’s practice over the years, and in this respect Arthur’s newly political role certainly built directly on the more purely lawyering role he had developed over the years.

His ability to speak in this manner caused the ANC members to have full confidence that when they asked him to draft, he would really take their views on board.

It is not surprising that a letter to Arthur from Skweyiya, the director of the ANC’s legal and constitutional affairs department, addresses Arthur as “Dear Comrade”.

Arthur’s responsibilities came to extend far beyond participating in the work of the ANC constitutional committee.

The ANC’s internal structures, Heinz Klug told me, were quite fluid, so it is not surprising that Arthur played a role in multiple contexts.

A number of members of the constitutional committee were also chosen in mid-1991 as members of the ANC’s overall governing body, the national executive committee, and Arthur would have influenced the NEC’s thinking throughthese colleagues as well.

As Arthur himself summarised his role: “I was asked really to be legal adviser to the ANC … The national working group, which was really the driving force, would have a meeting once every week on Wednesday and they would have a session on negotiations. I used to attend those sessions just to talk about the … legal issues which were arising.”

“Whenever there were bilaterals between the ANC and the National Party at the time of negotiations, there used to be three or four people who would go. It was usually Cyril Ramaphosa, Joe Slovo, Mac Maharaj, Jacob Zuma was there on occasions, and I would go, as the legal adviser, to be there just to discuss … what was happening. I went to big bilaterals which were taking place when they had large groups of people at the so-called bosberaads.”

As legal adviser to the ANC, his influence was pervasive.

It is likely that he played some role, albeit usually in the background, in almost every major controversy the ANC now faced in the course of the negotiations, from the terms of prisoner amnesties to the shaping of constitutional arguments and counterarguments.

And his role was far from mechanical; what he said was very likely to be adopted by the ANC as its approach.

The result was that even when Arthur came in 1993 to serve on the technical committee on constitutional issues during the last stages of the negotiations, his influence would not have been confined to the broad range of issues that were the business of that committee, because Arthur would have remained involved in other ANC constitutional discussions, notably as part of the constitutional committee itself.

Dennis Davis recalled attending a meeting led by Ramaphosa at the ANC’s headquarters at Shell House to discuss a particular point that was in dispute; “it was absolutely clear that once Arthur had taken the position that we had advocated, that was the end of the debate”.

Sheila Camerer, who was one of the government’s negotiators, similarly recalled that Arthur was extremely authoritative; if he said “this is the way it is”, everybody would take note.

Moosa, who worked very closely with Arthur in the negotiations, often meeting him on a daily basis, described Arthur as someone who did not appear pushy at all – unlike many senior lawyers – but instead was extremely persuasive and highly respected.

Moosa also felt that Arthur argued from what was right as a matter of enlightened thinking rather than what was good for the ANC.

Moosa emphasised that many people were part of the negotiations, but said that Arthur was more influential in the drafting of the interim Constitution than anyone else and by a long margin.

Van der Merwe similarly said that Arthur was so outstanding that he could take a position and explain its basis – and the matter would then be settled.

He also characterised Arthur as one of the most important and influential participants in the negotiations.

Niël Barnard, the former head of the government’s National Intelligence Service who became closely involved in the negotiations, referred to “heavyweights such as advocates Arthur Chaskalson and George Bizos, for whom the government’s politicians, with the exception of Tertius Delport, were simply no match”.

Hassen Ebrahim adds a related perspective: That it was because of Arthur’s knowledge and understanding of the law and constitutions, and the political conditions in the country, that he could present arguments of great value to the ANC.

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Get in touchCity Press | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Rise above the clutter | Choose your news | City Press in your inbox | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| City Press is an agenda-setting South African news brand that publishes across platforms. Its flagship print edition is distributed on a Sunday. |

Publications

Publications

Partners

Partners