SA’s role in World War 2 is undeniable, and German General Erwin Rommel led the decimation of a South African force in northeast Libya in 1941. This extract looks at the strategic ties that SA had with the British while going up against Rommel

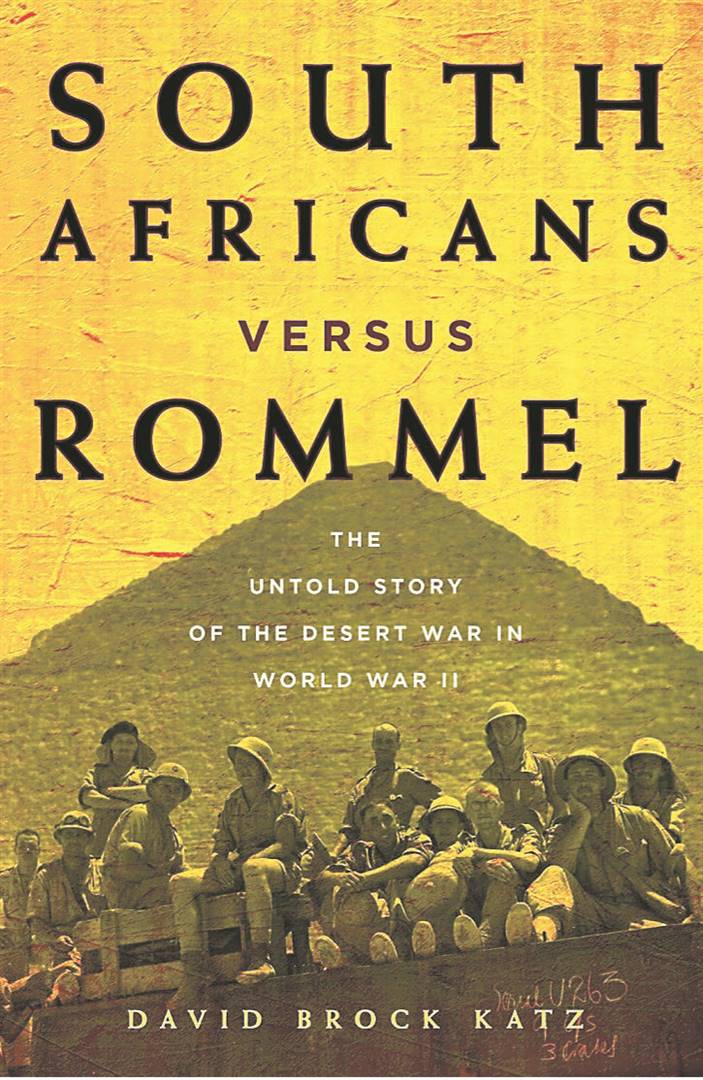

South Africans versus Rommel: The Untold Story of the Desert War in World War II by David Brock Katz

Jonathan Ball Publishers

R515 at takealot.com

Jan Smuts’ ‘Greater South Africa’ and the near invasion of Mozambique

It was fortunate for South Africa that Italian neutrality at the outset of the war, together with the remoteness of the European battlefields in relation to southern Africa, afforded the Union Defence Force (UDF) approximately 10 months in which to prepare for their first campaign in East Africa.

The relatively isolated South Africans were distant from the first catastrophes that befell Europe.

South Africa’s role, because of her diminutive military and remoteness, was limited to the provision of strategic resources and moral support to the British war effort.

This situation dramatically changed when France surrendered in June 1940 and the Vichy regime effectively became a German ally.

Germany’s easy defeat of France occasioned Italy’s belated entry into the war and added to the shift in power.

These two events fundamentally changed the balance of military power in Africa towards the Axis.

Great Britain counted on France as an essential military partner not only in Europe, but also in Africa. Britain did not envisage, by any stretch of the imagination, fighting a war against Germany or Italy without the aid of the sizeable French military.

The sudden demise of French military power placed Great Britain in a precarious position, creating a conspicuous lacuna in her defence policy that necessitated the immediate deployment of South African and empire forces to meet the impending Axis threat.

The British, in the absence of France, were reliant on the resources of the dominions and their considerable economic, manpower and military support to bolster her defences.

South Africa was required to play a significant role in aiding the UK in neutralising the Italians in Africa.

The French surrender, together with Italy’s declaration of war, suddenly placed the British east African colonies and Britain’s presence in Egypt in immediate danger.

The Italians hopelessly outnumbered the British in manpower and fighting equipment in north and east Africa.

The image of a courageous Britain facing the might of the rampant Axis powers alone was very far from the truth. The British enjoyed access to the massive manpower and economic resources of a vast empire.

France’s surrender immediately catapulted South Africa’s strategic importance.

Up to that date, the Union was dependent on Britain for most of her military needs. She would have to become self-sufficient and give way to Britain’s priority of re-equipping her devastated army in the wake of the disastrous Dunkirk evacuation.

It was a task that South Africa embraced energetically, and she not only achieved self-sufficiency militarily, but was able to become a significant producer of arms and munitions for the Allied war effort.

Furthermore, UK prime minister Winston Churchill, a long-time friend and admirer of then prime minister Jan Smuts, often took Smuts into his confidence; this was unlike his treatment of the other dominion leaders. Smuts became politically indispensable to Britain, being a great supporter and friend to Churchill, and somewhat of a military expert.

He became a field marshal in the British Army in 1941 and served in the Imperial War Cabinet, sharing a strong common belief in the concept of empire.

However, South Africa’s support of the UK was not entirely altruistic, nor based purely on loyalty.

Although the strategic threats to the British Empire and those facing South Africa did not coincide perfectly, there was a close strategic congruence when it came to imperial designs on Africa and South Africa’s latent expansionist interests.

South Africans in general regarded east Africa and especially Kenya as being in their backyard. Smuts, among others, had grand imperial designs of incorporating much of east Africa into a greater South African state.

At the heart of British-South African relations lay the general expansionist aims of the various South African governments who coveted the British High Commission Territories (HCT) – Swaziland, Basutoland, Bechuanaland and Barotseland, and other territories further to the north.

Smuts sought to form a united state stretching possibly to the equator, including South West Africa and southern Mozambique. Pretoria would be the actual geographical capital of the “Greater South Africa”.

The British were reluctant to feed South African expansionist aims by turning over the HCT in the face of the blatant racist attitude of successive South African governments and Afrikaner nationalist aspirations for an independent South Africa.

This denial of expansionist aims was one of the leading causes of political conflict between South Africa and Britain in the run-up to the World War 2.

One of Smuts’ goals on entering World War 2 was his intention to formalise South Africa’s territorial claim to South West Africa.

Smuts gambled on a reward for South Africa’s impeccable war record in the form of the formalised incorporation of South West Africa into the Union.

None other than Churchill encouraged him to annex the territory, but India dealt any chance of incorporation a final blow when it blocked the transfer at the United Nations, based on South Africa’s unacceptable racial policy.

A resurgent Smuts was behind the most extraordinary of all the bids to obtain Swaziland on the eve of World War 2. He attempted to resuscitate prospects for a Greater South Africa.

One of his first acts was the request to transfer Swaziland to the Union. His prime motivation was to strengthen his hand against the nationalists by taking advantage of Britain’s preoccupation with the war and gratefulness for South Africa’s support.

His act of brinkmanship diplomacy met with a sharp rebuff from Anthony Eden, the secretary of state for dominion affairs, in October 1939.

Smuts, not easily deterred, sent Deneys Reitz, the minister of native affairs, to once again broach the subject personally in London. Eden again issued strong words in an attempt to end the problem. The British sharply rebuffed Smuts’ attempts to force a hand over the HCT during the war years.

Smuts took the opportunity, on the occasion of the fall of France and Italy’s entry into World War 2 in June 1940, to advance to Churchill his understanding of the strategic role of South Africa in the defence of the British Empire in Africa. Smuts saw Africa as the next logical target for the victorious but largely idle German army.

He saw the Germans joining the Italians in first conquering French territory in north Africa and then moving inexorably southward, down to the southern tip of Africa.

Smuts considered South Africa crucial to the British retaining India, Australia and New Zealand. In his words: “To save the Empire and the Commonwealth it is, therefore, necessary to hold Africa south of the equator at all costs in this war.”

He continued to request a “number of British and Dominion divisions to be deployed to east and west Africa to assist the effort of South Africa”. Smuts saw Southern Africa as “... not a sideshow, but a vital area of empire”.

In his reply, Churchill politely disagreed with Smuts and insightfully considered that Adolf Hitler’s next move would be in an eastward direction in Europe.

One must contextualise Smuts’ opportunistic attempt to centralise the empire’s strategy towards Africa in terms of his desire to expand South Africa’s territory in an exercise of sub-imperialism. In 1938, Portugal’s African colonies barely survived Hitler’s dismissal of a British appeasement attempt to offer Portuguese African territory to satiate Germany’s European territorial demands.

If Portugal’s entry into World War 1 saved her African territories from being divided up between the UK and Germany, then her neutrality in World War 2 almost resulted in the UDF invading Mozambique soon after South Africa’s declaration of war.

The UDF had not been idle in the interwar period and had drawn up an elaborate plan for the invasion of southern Mozambique and the securing of the port of Lourenço Marques. Major Johann Leipoldt undertook the formulation of Plan Z after the armistice.

The UDF tasked Leipoldt, while he still served on the South West Africa Boundary Commission, to evaluate whether South Africa might become involved in military operations in Portuguese east Africa.

Given the long previous history of South Africa’s acquisitive desires for Delagoa Bay, it would be naive to assume a purely military role behind Plan Z. The need for a plan evolved from a perceived threat from Portugal in the interwar years.

There was a possibility that an Axis intelligence and military force would use Mozambique as a base. During the interwar period, Portugal strengthened her garrisons in her African possessions and made a topographical study of her borders with South Africa.

The activities of Portuguese intelligence officers and cartographers made Pretoria nervous.

The fact that the Portuguese were soon to reinforce their seven military aircraft in Lourenço Marques with an additional seven added to the general disquiet.

The establishment of some radio stations in Angola was of particular concern, as this had been the primary casus belli regarding German South West Africa.

World War 2 brought its insecurities regarding Mozambique and a possible Nazi takeover of Lourenço Marques. The UDF tasked Major-General George Brink with making a plan involving at least one motorised brigade to invade and seize Lourenço Marques if the need arose.

The controversial decision to go ahead if Italy entered the war was confirmed on June 10 1940. The UDF ordered the brigade commander of 1st South African Infantry Brigade to invade within an hour.

A breakdown in logistics and an inexplicable unavailability of fuel caused the delay of the operation. A shortage of vehicles and persisting fuel problems caused a further delay.

Despite all the problems, which included wireless sets not working and reckless driving, elements of 1st Brigade began to assemble at Komatipoort on the border by June 12.

The original bold plan of sweeping through to Lourenço Marques diminished to one of taking up defensive positions in Komatipoort.

This change of heart occurred in the face of overwhelming disorganisation, and perhaps intervention from a higher source.

South Africa came within a whisper of invading Mozambique and occupying Lourenço Marques, and, had the operation not faced logistic issues, the long dream of acquiring Delagoa Bay would have been a reality.

Publications

Publications

Partners

Partners