William Henry ‘Krom’ Hendricks was the first sportsperson to be formally barred from representing SA on the basis of race.

Hailing from Cape Town’s Bo-Kaap, he played in 1892 for the South African Malay team against the touring English, who insisted that he was one of the best fast bowlers in the world at the time.

In this extract from a book on his life, his story is told for the first time

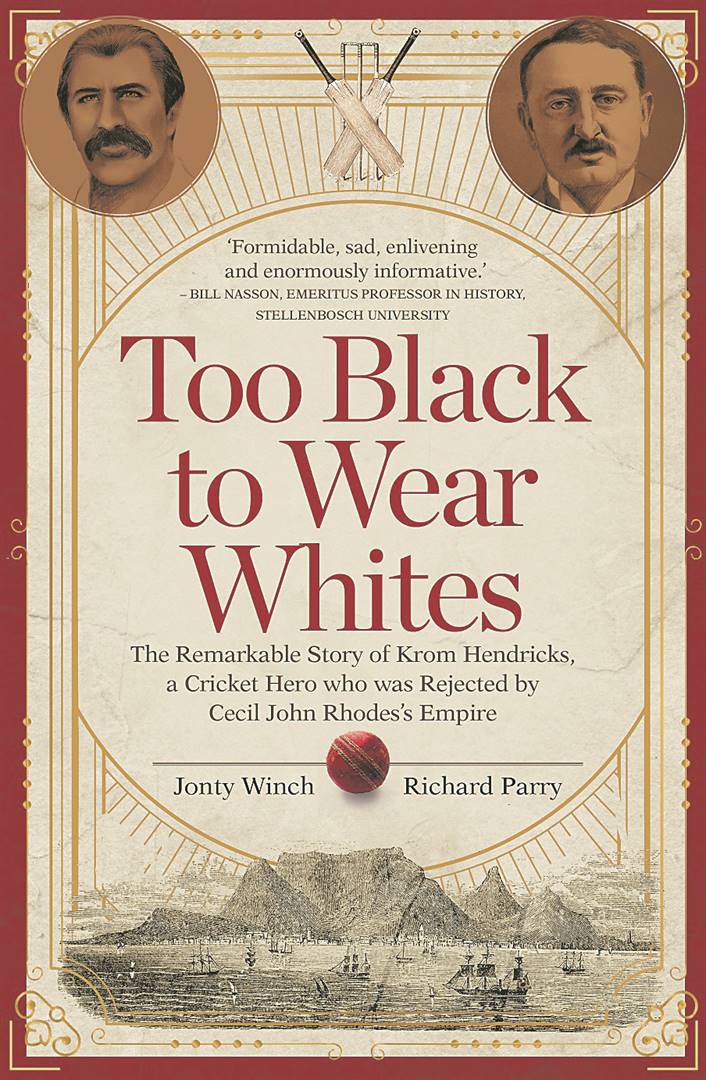

Too Black to Wear Whites by Jonty Winch and Richard Parry

Penguin Random House

276 pages

R260

The possible selection of Krom Hendricks in the South African touring side was to become a fundamental political issue in the Cape during the early months of 1894.

The unfolding controversy would involve the Cape government at its highest level and attract the attention of numerous prominent figures in the game.

The role of Malay and coloured cricketers in the broader social context was a key battle in the ongoing war over South African identity.

Harry Cadwallader, as the tour’s leading promoter, wanted the side to be the strongest possible combination and, given the available talent in black cricket, to be fully representative of the country’s population.

He was aware that Hendricks and E Ariefdien – as well as the Kimberley-based Armien Hendricks – were better bowlers than those in the white clubs.

He also knew that there would be opposition to his plan to include them in the touring side, but, by the end of 1893, he believed that the segregationist imperatives of the white establishment could be placated.

He envisaged a compromise that included selecting Malay players in a South African team, but, at the same time, emphasising the class role of black South Africans as servants on an unequal footing with whites.

Writing as Under the Bell in the South African Review, Cadwallader opened with a deeply defensive statement emphasising the fact that he knew just how much opposition he was likely to face in selecting black players.

“Now I am going to drop a thunderbolt,” he said, “which I know will shock a few prejudices.”

He continued: “There is serious talk of playing one or two coloured South Africans with the team if their cricket prowess is likely to strengthen the team, and there are two dark ones in view who might, in a wonderful degree, strengthen the bowling, where most weakness may be felt.

If it is decided to take them, they would of course be baggage men.

There is a strong feeling among English cricketers that such an introduction would of itself be an attractive novelty, and if they would make the team more representative, why not take them?”

Cadwallader had dual responsibility as a journalist (sports editor of the South African Review and cricket writer for the Cape Times) and secretary of the South African Cricket Association, and was central to all matters regarding the tour that he had been asked to organise.

He published a letter that called on players to avail themselves for the venture and then asked the major centres to consider likely candidates and submit nominations from their respective areas to the national selection committee.

The various unions were also asked to choose the side that they believed would be best equipped to represent South Africa on an overseas tour.

In the weeks that followed, there was much discussion as to the composition of the team, while Cadwallader maintained “constant communication” with Charles Alcock in England and hoped “any player selected to represent South Africa will not be prevented from any cause from playing”.

For several weeks, speculation centred on whether Hendricks should be chosen.

Those in favour of his selection were able to point out that he was easily the fastest bowler in South Africa.

The only player who rivalled him in terms of pace was Natal’s Peter Madden, who was believed – even by his own cricket authority – to be a “chucker” and was not considered for selection.

In the Transvaal, it was the stated ambition of Abe Bailey to see South Africa become a cricket power.

For him, as a representative of the mining industry, the importance of getting South Africa on to the imperial stage was far more important than the Cape’s parish-pump politicking around the class status of coloured players.

If making a big splash meant the inclusion of a coloured player, so be it. In fact, the likely impact and public interest that Hendricks would bring to the tour made it important that he be selected.

Bailey’s Transvaal cricket committee and, for the most part, the Johannesburg press, supported him on the Hendricks issue.

EJL Platnauer, the sports editor of the Standard and Diggers News, was persuaded that Hendricks was essential to the South African touring team’s success.

Interest in the fast bowler grew quickly and, on January 10 1894, Reuters carried a message that was published in newspapers throughout South Africa: “With regard to the proposed cricketing team for England, the [Transvaal] papers strongly advocate the inclusion of Hendricks, the Malay fast bowler, in the team.”

The issue was essentially a showdown between the different interests of the Transvaal mining industry and the Cape.

The Western Province Cricket Union had not yet accepted the necessity for it to be involved in the arrangements, thus creating an awkward situation.

It was the provincial body that would be called on to nominate Hendricks, a step that it was unlikely to take.

It suggested players might object to travelling with “a coloured man on equal social terms” and that “men declared they would rather stay than go with him”, but without providing any evidence.

Read: Book Extract: We Shall Not Weep by Johnny Masilela

In the Cape Times on January 11, Cadwallader decided to publicly support Hendricks by reminding readers that the player would be taken as a fast bowler and baggage man.

In that inferior role – one that sacrificed Hendricks’s dignity to team requirements – Cadwallader argued, “there could be absolutely no objection to Hendricks on account of his being Malay”.

Cadwallader, while seeking to maintain the Hendricks option despite popular prejudice, made a cardinal error. There was no effort to ascertain Hendricks’ own position regarding his ethnicity or interest before jumping to print. Hendricks was proud enough as a man and cricketer to resent having his status traded like a piece of meat in the national press without any consultation.

He responded quickly and forcibly in the January 12 edition of the Cape Times, strongly objecting to the fact that he had been characterised as Malay and stating that no one had made any attempt to establish his views on the subject of the cricket tour, his availability or the role that he would play: “Sir – I notice in this morning’s issue of your paper, under the heading of Sporting Intelligence, a wire from Johannesburg with your comment thereupon, wherein reference is made to my name as a possible candidate in the proposed cricketing team for England, and I hasten to take exception to same. In the first place, I must disclaim any connection with the Malay community. My father was born of Dutch parents in Cape Town, and my mother hails from St Helena – then why am I termed a Malay?

“Further, I note it is taken for granted that, should I be selected, I would go with the team, but, to the present, no such application has been made to me to ascertain my views on the subject and I think this was the least the committee could have done before making my name thus public.

“Then, Sir, as to your remark that I ‘might be taken home as baggage?man’, I would beg to state that, if chosen, I would not think of going in that capacity.”

The following day, a letter from a “coloured cricketer” explained the “difference between a Malay and a coloured man … not one coloured man out of six would allow another to call him a Malay to his face”.

The implication was that it was Hendricks’ desire to distance himself from the descendants of Muslim slaves who had arrived in the Batavian era in the 17th and 18th centuries, and identify himself with the “Christian ruling class”.

A Christian status offered opportunities for social improvement that were important to Hendricks, despite increasing concerns that the Cape’s social and political landscape under the Cecil John Rhodes government was undergoing a period of rapid and fundamental social, cultural and economic change.

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Get in touchCity Press | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Rise above the clutter | Choose your news | City Press in your inbox | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| City Press is an agenda-setting South African news brand that publishes across platforms. Its flagship print edition is distributed on a Sunday. |

Publications

Publications

Partners

Partners