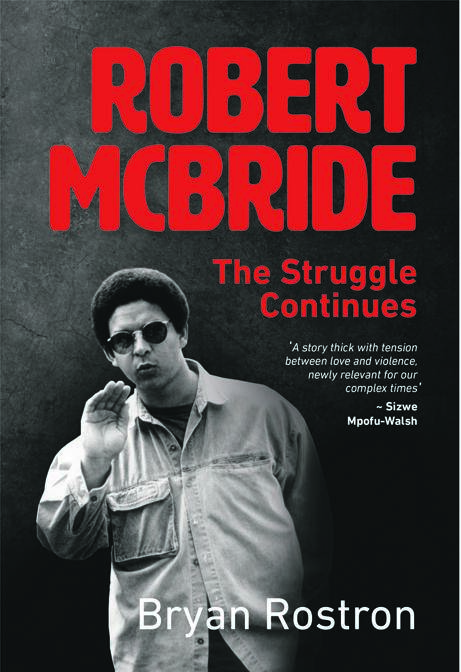

This is the story of Robert McBride and his comrades: the substation sabotage spree; rescuing a compatriot from hospital and smuggling him to Botswana; the devastating Why Not Bar and Magoo’s car bomb that killed three women; the dramatic trial; and McBride's 1463 days on death row

Robert McBride: The Struggle Continues by Bryan Rostron

Published by Tafelberg

Pages: 360

Price: R290

Judge Douglas Shearer delivered the verdicts on April 7 1987.

He and his two assessors gave Greta Apelgren the benefit of the doubt on the most serious charge; they concluded that the state had not proved she knew about the car bomb and acquitted her on all counts relating to the Magoo’s Bar deaths.

Robert McBride, however, was found guilty of murdering Angelique Pattenden, Marchelle Gerand and Julie van der Linde.

Both accused were also found guilty of aiding Gordon Webster to escape, and of harbouring a terrorist and helping to smuggle him out of the country.

A number of counts, especially against Apelgren, were dismissed.

Nevertheless, McBride was found guilty of furthering the aims of the ANC, as well as several counts of sabotage and terrorism.

But there was only one issue that dominated the next day’s headlines: “McBride CONVICTED OF THREE MURDERS.”

The trial moved into its final stage. This was the consideration of whether McBride should face the death penalty.

If extenuating circumstances regarding his “moral blame-worthiness” were agreed by the judge and the assessors, a life sentence could be imposed instead.

Throughout the past two months, David Gordon had been desperately trying to get one of the injured victims of the Parade Hotel car bomb to stand up and testify in mitigation for his client.

But no one who had been in either the Why Not Bar or Magoo’s on the night of the explosion was prepared to come forward.

There followed three days of legal argument and debate over McBride’s fate.

Gordon made a moving and emotional appeal for extenuation. He said: “This case is a South African tragedy.”

He pleaded McBride’s youth, his political commitment, the violent community in which he had grown up and the injustice against which he was fighting.

He evoked the memory of Major John MacBride, who was executed after the Easter 1916 uprising in Ireland “because of his role in the Boer War, which was still held against him”.

Gordon compared this with the treatment of defeated Boer leaders at the end of the war who were forgiven (and in one prominent case, reprieved from execution) in the name of reconciliation.

Gordon pleaded for mercy and understanding.

The law was clear.

In South Africa, the death sentence was mandatory for murder unless extenuating circumstances were found to lessen “moral blame-worthiness”.

That would be decided by a three-way vote between Judge Shearer and his two assessors.

Professor John Milton was opposed to the death penalty on principle; he also felt that the political nature of the case provided substantial grounds for mitigating factors.

As the trial drew to its conclusion, however, he realised that Shearer himself had come to the opposite conclusion.

This left Brian Leslie. Milton had no idea which way he was thinking.

Shearer insisted that the decision should be made as soon as possible because he did not want the agony of the prisoner to be drawn out longer than was necessary.

When the court went into recess at the end of that week, after the culmination of two and a half months of detailed legal argument, Gordon felt that there was a very good chance his client would not be sentenced to death.

The judgment was due to be delivered on Monday morning.

In his chambers, Shearer told his two assessors that they must ponder dispassionately over the weekend what their verdicts were going to be.

Before they drove off that evening, Milton tried hard to convince his colleague Leslie that there were sufficient extenuating circumstances to permit a life sentence instead.

He put forward five principal reasons: McBride’s lack of maturity; the influence of his father’s obsessive hatred of whites; the anger caused by the declaration of the state of emergency; that the initial target had aimed to destroy property not lives; and finally that the Marine Parade decision had been made on impulse after a suggestion from Mr C.

Yet Milton was unable to gauge Leslie’s reaction. He appeared to concede the points without being enthusiastic.

Milton rang him on Friday and reiterated his arguments. He thought he might be able to persuade him.

If he could, it would be two to one against Shearer and the death penalty.

“If you feel you need to talk about it more,” offered Milton, “come over to my house any time during the weekend.”

On Monday morning, April 13, Milton parked his car outside the Supreme Court.

He saw Leslie on the other side of the parking lot; he knew immediately what he had decided.

Leslie came straight over to him. He was very tense. “I can’t find any extenuating circumstances,” he said.

Even though Apelgren did not risk such severe penalties, Margaret Apelgren could not face attending the court that Monday.

Instead, she stayed at home and prayed.

Doris McBride felt she was close to the edge of a breakdown. That morning, she was accompanied by her daughter Bronwyn and her sister Girly.

“If they pass the death sentence, just don’t cry,” Doris told them fiercely. “They are waiting to see us break down.”

The court was so crowded that there were people queuing in the corridor.

The security police, fearful of a riot, were out in force. The court was also full of police. The atmosphere was volatile.

As McBride was being brought up from the cells below the court, a policeman dangled a rope in front of his face.

McBride lunged at him and there was a scuffle.

The police immediately announced that they intended to clear the court; McBride was in an aggressive mood, they said, and could cause mayhem.

Gordon hastened to see Shearer in his chambers. He would take personal responsibility for controlling the public gallery, he said.

The lawyer, still hoping his client would not be sentenced to death, went out into the open court and begged for calm.

“I appeal to everyone,” he said. “Whatever happens, we all must maintain the dignity of the court, as much as the accused has respected the dignity of the court.”

Gordon handed McBride a tie and thought: a rope could be going round his neck.

Then Shearer entered Court A, followed by Milton and Leslie. There was absolute silence as he read out the sentences.

Greta Apelgren was a good person, he said, and it grieved him to have to sentence her, but a substantial portion of her sentence would be suspended.

Apelgren was effectively sentenced to one year and nine months in prison.

The ritual took only 15 minutes.

Shearer turned to McBride and said: “It is with great sadness that the court is forced to conclude that there are no circumstances that extenuate his guilt on counts 14, 15 and 16.

“On count 14, I am obliged by law to sentence accused Number One to death. On count 15, I am likewise obliged to sentence him to death, and on count 16, I am obliged to sentence him to death, which I do.”

Milton did not know where to look; he looked at McBride.

The condemned man was staring fixedly ahead, betraying no emotion.

Milton noticed that Apelgren put her hand lightly on McBride’s hip. Shearer rose and, followed by his two uncomfortable assessors, filed out of Court A.

Doris McBride was staring at her son’s back. The court was still hushed, uncertain.

McBride appeared to be very still. Then he turned and addressed the public gallery.

“I have taken you quite a distance along the road,” he said.

“Freedom is just around the corner. I am leaving you at the corner – and you must take that corner to find freedom on the other side.”

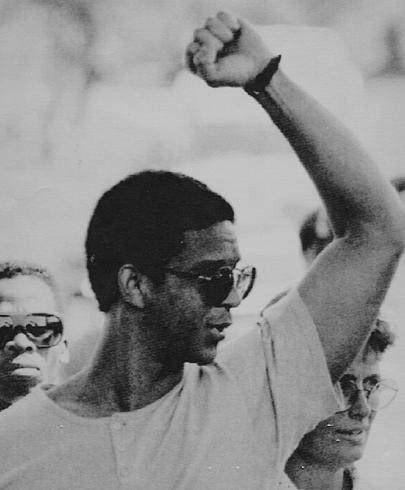

As the policemen moved towards him to take him away, McBride raised his fist and shouted: “The struggle continues till Babylon falls!”

Publications

Publications

Partners

Partners