Born in Soweto into an anti-apartheid activist family Lindi Tardif lost her father when she was young and her grandfather was exiled. Today, with four degrees under her belt, she works for Amazon in Seattle, US, and has published her inspiring story of how human values, faith and choices have shaped her success. In this extract, she is a schoolgirl

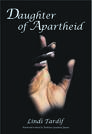

Daughter of Apartheid by Lindi Tardif

Elm Hill

132 pages

R119 for the e-book at takealot.com

R140 for the paperback at amazon.com

Trigger warning: rape culture

One day when I was about 16 years old, I was returning home from Sacred Heart. The taxi dropped me off on Tema Street, and from there, I walked the third of a mile to my grandmother’s house. A car suddenly appeared alongside me, its windows rolled down and three guys inside.

The car was ordinary – a light-brown, four-door sedan – as were the guys, who appeared to be around 18 or 20 years old. I can’t tell you much more than that because I was trying very hard to keep looking ahead. I knew that giving them more than a quick glance would be interpreted as an invitation to continue.

“Get inside,” one of them said to me in Zulu. His voice was sort of friendly, but this was a command, not a request. I walked on, not responding. He kept repeating the command as the car rolled along beside me, matching my pace. I just kept walking and looking straight ahead, engaging with them as little as possible.

I’d been propositioned by neighbourhood boys before, even by tsotsis, but they left me alone once they realised I was not interested and would not accede to their demands. The show-no-interest-and-dig-your-heels-in strategy usually worked, but this time it failed. The car kept rolling along beside me, with the guy growing more and more insistent.

Then it dawned on me: this was more than a proposition. Oh, my God! I thought. I’m being jackrolled!

Jackrolling might seem like a quaint expression – cute, almost – but it was the worst thing that could happen to a woman. To be jackrolled meant to be snatched off the street by a group of guys, stuffed into their car, driven off somewhere, and raped repeatedly, at least once by each of the guys, maybe more. Most women who were jackrolled did not live to tell the tale.

I knew that once you were in the car, you were finished, so I kept walking, staring, and strolling ahead as if nothing was wrong, for to show any sign of weakness would spur them on.

“Come on, cutie, get in,” one of them ordered in Zulu again. I could hear the others saying something to each other but couldn’t make it out. I kept walking.

I had repeatedly refused to obey [orders], and now they were angry. They continued driving slowly alongside me, their voices increasingly insistent, their tone growing louder, and their words harsher. People saw what was happening and started gathering in a group near the corner of Tema and Mzinyane Streets.

In what seemed like a few seconds, there were about 20 people standing in front of the house, watching. Just watching. No one said anything, no one challenged the guys, no one motioned for me to hurry into their house. That wasn’t how things were done, even though many of these people recognised me, and some even knew my family.

You just didn’t get involved; it was too dangerous. If you intervened, the jackrollers would come after you right there and then, and the police wouldn’t protect you, as they were generally absent. (You couldn’t just summon them with a 911 call.) Nobody dared do more than stand there. The neighbourhood watched this drama unfold as quietly and passively as if they were watching an episode of a crime show on TV.

And me? I just kept walking, looking ahead, letting my body language signal “no” over and over again, not getting in the car, and not allowing my body to betray any anger, any fear, any anything. I knew the worst thing I could do was to show fear or to cry, for both would be seen as signs of weakness.

Then one of them hopped out of the car. He was thin, of medium height, with short hair. Nothing about his appearance was memorable except the menace in his eyes. I knew he was going to grab me. I stopped dead in my tracks, knowing that I had to stand my ground. Doing so probably wouldn’t help, but to back down, cry, or run would certainly lead to disaster.

I was terrified. There was no way I could get away from these three guys, and no one was going to come to my aid. There was nothing to do but ask for help. Oh God! my heart cried out. You have to help me! I’m not going to convince these guys to let me go, and no one is helping me.

I just stood there, hoping something would happen. Then suddenly, one of the guys in the back of the car said: “Yazini? Yekani les’ sfebe!” – meaning, “You know what? Leave this whore alone.”

“Ja,” said the driver, “yeka les’ sfebe.”

Without a word, the guy I feared would grab me sauntered back to the car and got in, and they drove off. And that was that; it was all over. People returned to their homes as quietly as they had come out. No one asked me if I was all right, no one gave me a reassuring smile, and no one nodded a greeting. It was just another day, another almost-jackrolling, another incident that filled the neighbourhood with fear and anger that no one would acknowledge, for living with intimidation was so very routine.

IT’S ALL ABOUT CHOICE

I haven’t thought about this much over the years because it was, indeed, so routine. And now I realise that it had to remain routine in my mind; otherwise, I might have broken down in tears.

There wasn’t anything I could do about jackrolling, life in Soweto, or apartheid [South Africa] – except to make the choices I believed would help me make a better life for myself someday, somehow.

I had to choose to avoid compromising situations with boys that could lead to my becoming a parent before I was ready, choose to steer clear of friends who were bad influences, choose to get the best education available to blacks, and above all, choose to hold on to my faith and remain strong.

That was my only power: choice.

Even though we as a people hardly had any power of choice, the idea that I had choice and the responsibility to exercise it wisely was ingrained in me from an early age. My mother, Esther Happy Langa, never told me I couldn’t drink, smoke, do drugs, neglect my homework, hang out with boys, or anything else.

Instead she said: “Lindi, you have the freedom to do whatever you want, make any choice you like. But remember: you are not free from the consequences of that choice.” She was teaching me an important lesson, which was that life doesn’t “just happen”.

Instead it is driven by the many choices we make. Yes, there are limitations created by choices other people have made, often before we are born. Apartheid slapped severe limitations on the lives of all of the “others”, and there were additional restrictions imposed by family, economic circumstances, geography, and other factors. But no matter how bound our lives may be, there are always choices to make, and we are always affected by the results of those choices.

When the jackrollers pulled up beside me, I chose not to break down and cry, and I chose not to comply. I made the choice to risk infuriating them by demanding my dignity and saying no. Things might have gone much worse for me because of this, and other women may have gotten into the car in hopes of keeping the damage level low, relatively speaking, or maybe even talking the jackrollers out of it.

Those were common strategies, and it’s not for me to judge others. When you’re in that situation, your fear level leaps off the charts, and you grasp at any straw that pops into your terrified mind.

I can only say that for me, the choice was clear: even if they beat me fiercely because of it, my answer was no. I felt that if I didn’t stand my ground, I would be raped multiple times, possibly impregnated, or killed – so my answer was no. I was not getting in that car!

That was my choice, and I was willing to accept the consequences of making it.

Publications

Publications

Partners

Partners