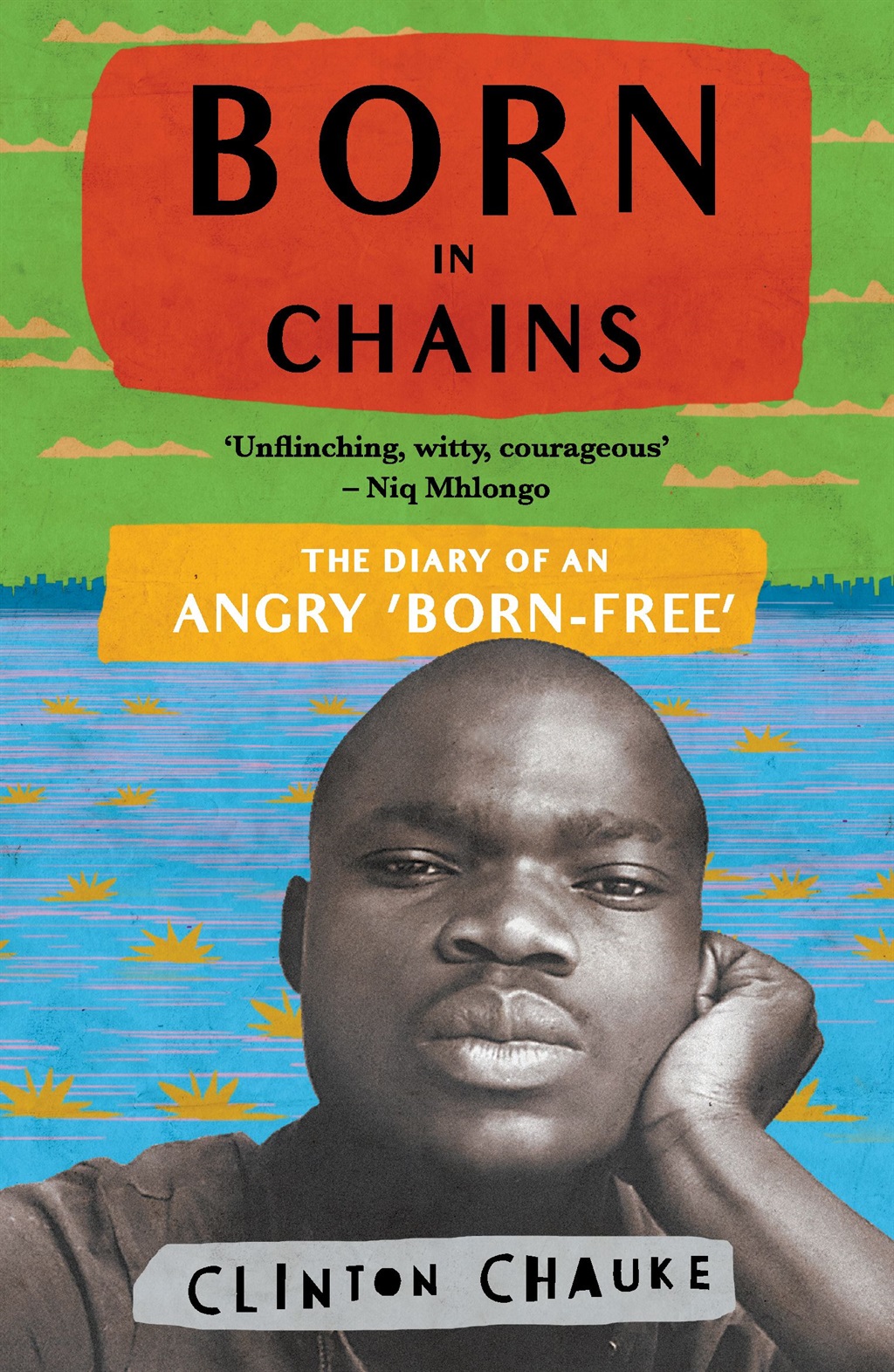

This is an extract from Chapter 22, titled #FeesMustFall, in Born in Chains: The Diary of an Angry Born-Free by Clinton Chauke

Born in Chains: The Diary of an Angry Born-Free by Clinton Chauke

Published by: Jonathan Ball

Price: R169

I was not the only student experiencing the frustration of university fees. A lot of students were in a similar situation. Growing up, we were told that we could be anything we wanted to be, but then we realised that we had to pay for it. The goalposts had been moved. We observed that, when a country sells something that is supposed to be basic, like education, it becomes self-defeating.

When you put a price tag on anything, you invite inequality. Where there was a price tag, there would always be class.

We finally decided to stand up and raise our concerns using the hashtag #FeesMustFall. The protests started at the “real” university, Wits, and spread to ours. Wits students rejected the 10.5 per cent university fee increase proposed by the minister of higher education, Blade Nzimande.

I still remember the day it started on our campus. I was in my room at Robin Crest and I heard chanting and singing outside. I thought it was the normal call of vimba.

But the singing grew louder and louder. I then went outside, on to the balcony, and realised that whatever the occasion might be, it was huge.

“The guys are protesting against the university fees,” my roommate Lebogang Maphuthuma told me.

I started to have hope that my debt might be cancelled. I quickly jumped into the lift, went all the way down to the ground floor, and joined the guys on Saratoga Avenue.

We marched all the way to Braamfontein, where we met up with Wits students. For the first time, the Wits students acknowledged that we were also university students. It was beautiful to see the students in solidarity. Even the white students joined us. Solidarity was crucial in our cause.

Our protest was aligned with #RhodesMustFall, demanding the removal of the Cecil Rhodes statue at the University of Cape Town. Their campaign had spread across the country and demanded that my favourite statue at Church Square be removed. I didn’t believe that taking statues of dead white men down would bring me any justice. Yes, those statues represented centuries of ancestral pride, but taking them down wouldn’t ensure equality in this country.

As for me, I was focused on the elephant in our room. Like #RhodesMustFall, our campaign also spread across the country. We were organised.

It was said that we were all going to Pretoria to demonstrate at the Union Buildings, where the president was scheduled to address us.

On October 23 2015, I woke up very early in the morning and, with my friend John Mabe, I took a Mega Bus from campus and headed to Pretoria, my hometown. We arrived at Madiba Street and joined thousands of other students who were singing and chanting, holding up placards reading “Fees Must Fall”.

Songs and singing have always been a centrepiece of the African people. When we were happy, we sang. When we were sad, we sang. When we protested, we also sang, and had been doing so since the pre-1994 struggle years.

From Madiba Street, we marched – and others danced – to the big lawn outside the Union Buildings. We marched on the same streets that the women of 1956 had marched on. I could feel their strength; having grown up in a household of women, and continuing to be surrounded by them, I knew the power they represented and how resilient they were. When the guys started singing, “My mother was a kitchen girl, my father was a garden boy, that’s why I am a communist!” it almost reduced me to tears. It reminded me of my own parents.

The struggle songs raised our spirits higher, but one song in particular energised us: “Iyho uSolomon”. It was the leading song on that October day. “Iyho uSolomon” was a praise song for struggle hero Solomon Mahlangu. This was a great change of pace: for centuries, on the African continent, we have been taught to praise and worship someone who was humble and forgiving and non-violent.

I guess you know who I’m talking about. So, in Madiba Street, we stepped forward with our arms stretched out, then gave a huge clap like we did at His Rest.

“Iyhoooooooooooooooooooo! uSolomon! So-lo-mone! Iyhoooooooooooooooooo! uSolomon! Waye yisotsha, Iso-tsha lo-uMkhonto weSizwe! Wayo bulala amabhunu eAfrika! (Oh Solomon! The uMkhonto weSizwe [Spear of the Nation] soldier who killed the Boers in Africa!)”

Solomon was born not far away from where we were, in the township of Mamelodi. He died at the age of 22.

He had left the country when he was 19 to be trained as an uMkhonto weSizwe soldier in Mozambique and Angola. He came back to the country through Swaziland in 1977 carrying guns, grenades and ANC pamphlets.

Entering a taxi rank in Johannesburg to take the taxi to Soweto to commemorate the June 16 student uprising, he was stopped by the apartheid government police. He panicked. Shots were fired. Some onlookers were shot dead, and others injured. Solomon was charged for murder under provisions of the Terrorism Act of 1967.

On April 6 1979, the date on which Jan van Riebeeck had arrived in South Africa in 1652, Solomon was sent to be hanged at Pretoria Central Prison. His hanging caused an international scene. The police decided to bury Solomon in Atteridgeville, afraid that there would be violent protests if his funeral were held in Mamelodi.

The late ANC president Oliver Tambo said this of Solomon Mahlangu, while delivering the Spirit of Bandung speech in Lusaka: “In his brief but full life Solomon Mahlangu towered like a colossus, unbroken and unbreakable, over the fascist lair. He, on whom our people have bestowed accolades worthy of the hero-combatant that he is, has been hanged in Pretoria like a common murderer. Alone the hangmen buried Solomon, bound by a forbidding oath that his grave shall remain forever a secret, because, in his death the spirit of Solomon Mahlangu towers still like a colossus, unbroken and unbreakable, over the fascist lair.”

In April 1993, Solomon’s body was reinterred at the Mamelodi Cemetery, where his most famous and inspiring quote was inscribed on his tomb: “My blood will nourish the tree that will bear fruits of freedom. Tell my people that I love them. They must continue the fight.”

The song brought out the brave side of each student at the Union Buildings on that day.

In the crowd, I heard one of our students say, “The youth of 1976 have betrayed the youth of 2015.”

That made me think hard: the people who were in power had been in the struggle yesterday. Higher Education Minister Blade Nzimande had provoked us earlier, before the march. In a press conference, he had been caught on camera, joking that, ‘If the students don’t accept this, we’ll start our own movement, #StudentsMustFall,’ before bursting out laughing.

His comments may have been light-hearted and intended as a joke, but we didn’t have time to laugh. #StudentsMustFall trended immediately.

Although we had taken our inspiration from the youth of 1976, that student was right: they had betrayed us. They looked like they were clueless about our attempts to end our deprivations.

We continued singing at the Union Buildings until some small mobile toilets were set on fire. Helicopters started hovering over us, dropping teargas bombs and shooting rubber bullets and stun grenades.

Some of our students started forcing their way beyond the barricades to the Union Buildings. Police nyalas, which had been on standby, started driving up and down, trying to contain the students.

President Zuma was scheduled to address us after his meeting with vice chancellors and student representive councils. In the afternoon, a zero per cent fee increase for the 2016 academic year fees was announced live on national TV instead.

The outcome of the meeting was good for some students, but not for me. My debt still stood. What I wanted to achieve from the march was to see my debt scrapped, along with all the historical debt dating back to the year in which I was born: these debts, coupled with black tax, were the real challenges prohibiting us young blacks from making a meaningful contribution to the economy.

Since my debt still stood, I would automatically be excluded from the university. The outcome of the meeting was a failure to bring about free, decolonised education.

We had failed to dismantle the anti-black system that maintained black oppression in our time. President Zuma even failed to come and address us. I was angry because I hadn’t seen him.

As soon as the announcement was made, I took John around the city. By the time we got back to the Union Buildings, the Mega Buses had left us behind. We took the taxi known as ‘Pheli-Via-Church’ to my home in Atteridgeville.

I have never been as embarrassed in my life as I was that day. My home was not as beautiful as the houses I’d been showing John around town. It was worse because there was no electricity that day at home. But John was a cool guy. He didn’t have a problem with where I lived. He was just fascinated by the living conditions of Mshongo.

Publications

Publications

Partners

Partners