There are many similarities – both disturbing and inspiring – between our present and past battle

The zeitgeist as expressed in language, behaviour and policy today, vis-à-vis the Covid-19 coronavirus, has an uncanny similarity to the days of apartheid.

The parlance that predominates in this time of the virus includes Wuhan, virus, pandemic, lockdown, border closure, testing and screening, masks and tracers, ventilators, vaccines, social distancing, personal protective equipment (PPE), fake news, isolation and quarantine.

Wuhan will forever be associated with the germination of the virus, much as South Africa was synonymous with apartheid before 1994.

Just as the initial outbreak of Covid-19 was dismissed as common flu, or – at worst – pneumonia, the world did not pay much attention to the racial discrimination that existed in South Africa prior to the institutionalisation of apartheid by the National Party, which assumed power in 1948.

And just as this “flu” would soon be recognised as something far more virulent, so would the UN declare apartheid to be one of the most virulent forms of social engineering conceived by mankind.

The UN would declare apartheid a crime against humanity in 1973.

In the current world, the World Health Organisation (WHO) declared the virus to be a pandemic in February 2020.

It spread quickly from China to Italy, Spain, France, the UK and – devastatingly – to the US, other sections of Europe, Asia and Australia.

For a brief moment, the African continent appeared immune.In South Africa, the initial cases of the disease were individuals who had travelled from Europe, largely from Italy.

Clearly, we had to assume a defensive position.

Our government quite correctly invoked the Disaster Management Act. Some opinion makers were relieved that a state of emergency had not been declared, given the concomitant draconian restrictions on the rights of individuals.

The last time a full national state of emergency was promulgated was in 1986, by former prime minister PW Botha.

It was lifted by then prime minister FW de Klerk four years later.

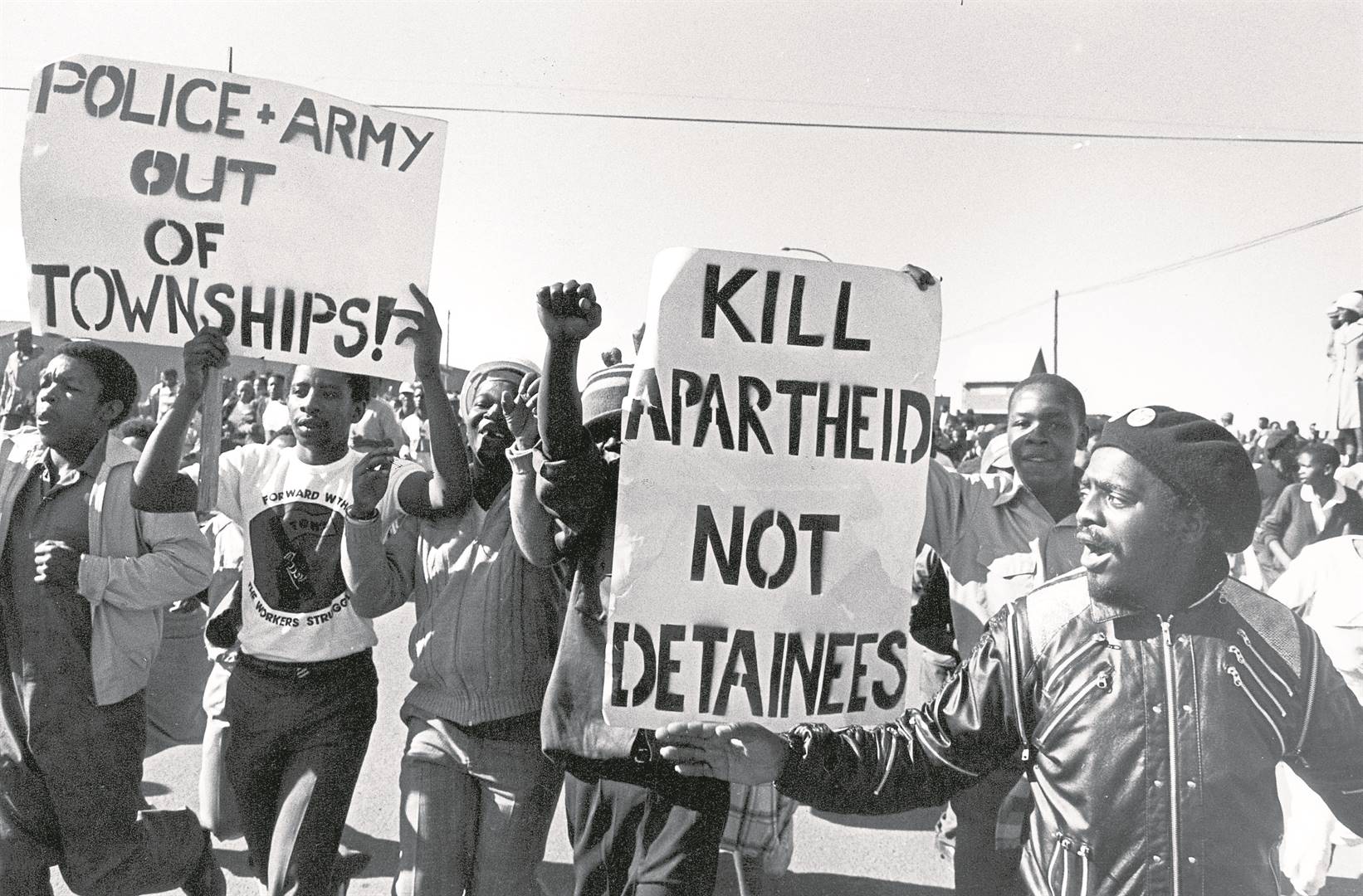

Prior to that, the apartheid regime declared a state of emergency on March 30 1960, nine days after the Sharpeville massacre, where a peaceful protest organised by the Pan Africanist Congress had been met with extreme violence by police, culminating in the deaths of 69 protesters.

Widespread arrests around the country included those of Chief Albert Luthuli and Robert Sobukwe, while apartheid laws were consolidated.

The government also used the event to establish bantustans, enforce Bantu education and impose influx control, while granting unprecedented power to the security police to detain and torture people at will, without charging them.

Hundreds of anti-apartheid activists suffered this fate and many were murdered in detention. Others went into voluntary exile.

The state of emergency intensified an already oppressive police state into a period of pervasive, brutal, state-sanctioned human rights abuses.

Social distancing

Today, in terms of the Disaster Management Act, which has been implemented in response to Covid-19, the government has the power to regulate the movement of people and goods internally and across the borders.

During the apartheid regime, there was also no recognition of borders, evidenced by regular cross-border raids into Lesotho, Botswana, Swaziland, Zambia, Zimbabwe and Angola.

These wanton incursions of boundaries brought mayhem and destruction, fear and death to both locals and neigbouring populations.

Apartheid, in fact, respected only its own internal ethic, demarcating black shantytowns (euphemistically called townships) from white areas and enforcing this by the Group Areas Act.

Some townships were further segregated into a Sotho section, a Zulu section and so forth. One such area was lucky because it had a unitary section consisting of Sothos, Shangaans, Ngunis and Vendas, thus its cynical name: Soshanguve.

These ethnic groups did not qualify to be citizens of the multiborder Bophuthatswana bantustan.

The Group Areas Act also prevented any racial groups deemed “non-white” from working in white areas, unless they obtained a special permit to do so.

Black people (especially men) found in white areas after 9pm could be forced by police to produce a “pass” (signed by a white citizen) or face arrest, imprisonment or – in many cases involving younger males – judicial caning.

I have always understood lockdown to be an American expression, referring to the good guys shutting down a city to take down the bad guys.

In our country at the moment, the term has been invoked to ensure that community transmission is stemmed by the “stay home” declaration: a state of national house arrest.

Apartheid’s Group Areas Act was accompanied by forced removals, starting in 1954.What was apartheid, if not a form of what we today call social distancing? Back then, it was distancing by kilometres, not just 3m!

Thousands of political prisoners, including the likes of Nelson Mandela and Walter Sisulu, were forbidden from touching visiting family members and were compelled to talk to them from behind a glass screen.

Screening

Screening is another Covid-19 buzzword, referring to the medical testing of an individual’s temperature, throat and nose to ascertain whether they have the virus.

Read: Coronavirus testing takes off in SA after weeks of delay

Apartheid’s version of screening was the Population Registration Act, which stipulated that South Africans be classified according to their so-called racial characteristics: a completely fallacious criterion.

Rather than dealing with symptoms such as a dry cough or fever, it involved deciding whether a person’s skin colour was light enough to be deemed white and the humiliating pencil test, in which a white bureaucrat inserted a pencil into a person’s hair.

The pencil would glide through straight (white) hair, but not though kinky (black) hair.

On this grotesque basis, the lives and freedoms of hundreds of thousands of individuals were decided.

Another form of apartheid testing involved the regulation that black children be at least seven years old before starting school.

A black child without a birth certificate proving their age was asked to put one arm over their head and touch the opposite ear.

If the child could not do this, they were told to stay home for another year.

To track down individuals who might have been infected with Covid-19, our government has galvanised tracers countrywide.

Apartheid had its own tracers – informants who were paid (or otherwise rewarded) to hunt down activists and enemies of the state, and have them handed over to the security police.

These traitors were called impimpis or askaris.

Isolation

In the Covid-19 lexicon, isolation is either self-imposed or regulated by health professionals to prevent transmission of the virus. But for those of us who lived under apartheid, the word has more sinister implications.

The brutal treatment of Sobukwe – founder of the Pan Africanist Congress – comes to mind. Considered the most dangerous man in South Africa, Sobukwe was arrested and kept in solitary confinement in a two-room house for no less than six years.

Ruth First (wife of Joe Slovo) was kept in isolation under detention for more than 180 days, while Winnie Madikizela-Mandela endured a series of house arrests, as did hundreds of others.

Masks

Masks have always been associated with bank robbers to prevent facial recognition.

In today’s world, they have turned South Africans into faceless people, but with good reason.

Masks are the first line of defence from being infected with Covid-19 and transmitting it to others.

Survivors of the Boipatong massacre of June 17 1992 recorded stories of white masked men among the 300 Madala Hostel dwellers who brutally stabbed, clubbed and shot dead 45 residents of this Vaal township.

A favourite form of torture employed by apartheid’s Security Branch was placing a wet canvas bag over the head of a detainee being interrogated.

Victims would then experience suffocation and a drowning sensation.

Few would be stoical enough not to break down. Intermittently, the bag would be removed, giving the victim a few gasps of air and encouraging him or her to provide information.

Covid-19 affects the throats of patients, causing a frightening death by obstructing the lungs and airways.

The warriors and the arms

The deleterious nature of apartheid was not discriminatory. It left both oppressed and oppressor tarnished.

Even the gradual relaxation of apartheid offered no immunity to this virulent system.

There was no vaccine. It had to be destroyed.

In the war against apartheid, the ANC organised Amadelakufa (the resistance) and, later, Umkhonto weSizwe, while the Pan African Congress formed uPoqo, later the Azanian People’s Liberation Army.

These armed movements were, in a manner of speaking, the first responders to combat apartheid. The Azanian People’s Organisation would also have its military wing, the Azanian National Liberation Army.

Covid-19 has our dedicated health workers and essential services providers as first responders.To help fight the virus, these responders require PPE.

Read: Covid-19: Discontent among healthcare workers on the frontline

Apartheid’s responders went underground, working in cells and using noms de guerre to protect themselves and their networks from arrest – all at immense personal sacrifice.

Sanitisation

To counteract international sanctions and condemnation, the apartheid regime embarked on a public relations campaign in international forums.

These campaigns sought to sanitise an indefensible system through lies and disinformation: apartheid’s fake news.

Covid-19 has had its own fair share of fake news and, worse, conspiracy theories.

The lesson learnt here is that we should listen only to the scientists and other credible sources of information.

The daily local and global statistics of Covid-19 are categorised according to infections, deaths and recoveries.

These recoveries give us hope that the virus can be beaten. Under apartheid, recovery was slow and agonising.

Even now, 26 years later, its legacy persists, manifested in the economic inequalities between blacks and whites.

It took over 40 years to destroy institutionalised apartheid, but destroy it we did.

Equally, we South Africans will be victorious against Covid-19.

We’ve been there before. We shouldn’t be afraid, but neither should we be complacent.

We welcome international assistance, but our history teaches us that it is our own determination, courage and discipline that will ultimately destroy the virus.

We, the people, are the vaccine.

Vundla is a businessman who describes himself as an independent

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Get in touchCity Press | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Rise above the clutter | Choose your news | City Press in your inbox | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| City Press is an agenda-setting South African news brand that publishes across platforms. Its flagship print edition is distributed on a Sunday. |

Publications

Publications

Partners

Partners