I am originally from north Sudan.

Growing up in privileged circumstances in the capital, Khartoum, I witnessed around me the casual racism and disregard for the darker-skinned, overwhelmingly poorer Christian southerners.

Years later, when I moved to the UK, I found that I was now on the other side of the divide.

I was the one who was dark-skinned and, as a Muslim, belonged to a minority often seen as problematic and insular.

My writing voice sprang up from this marginal place of being an African Muslim in the UK.

When I learnt to dig into my subconscious mind for childhood memories to use in my writing, I remembered not only the positive things that I missed about Sudan, but also things about which I didn’t want to think.

I remembered the quiet southern Sudanese who moved as if they were in the shadows – always treated as if they did not belong; always treated as if they were not Sudanese enough.

In 2011, after a bloody and bitter civil war, the overwhelming majority voted for independence from the north.

Now Sudan is a very different country from my days living there in the 1970s and 1980s. Its physical borders are no longer the same.

There is now Sudan (meaning north Sudan although the ‘north’ is omitted) and South Sudan with Juba as its capital.

You may know already the reasons for the split between north and south Sudan.

It was not only the policy of separate development, established during colonial times, but also the failure of the government in Khartoum to develop the south and spend oil revenue on its infrastructure.

Added to that was a distasteful propaganda campaign against southerners and, to top it all, the insistence by the north that the only identity Sudan could have was an Islamic-Arab one.

This alienated the largely Christian south and led to a bitter and detrimental divorce in which both sides sustained heavy losses.

But is religious and ethnic harmony easy? I believe it is necessary but how can it be achieved?

How does it feel, if you have faith in yourself or if you have been brought up to follow specific beliefs and values, to come into contact with others who have different ones? It can be a shock.

It is essential for children to know that there are people in the world who see it differently from their parents; who have different beliefs and values.

And these different people might not necessarily live on the other side of the planet. They are here, sharing the same schools, supermarkets and streets.

Practically speaking, children might not be able to come into enough contact with people of diverse backgrounds, but reading literature offers this opportunity.

Malorie Blackman, the successful children’s author of the series Noughts & Crosses and until recently the Children’s Laureate in the UK, said in an interview: “Books allow you to see the world through the eyes of others. Reading is an exercise in empathy; an exercise in walking in someone else’s shoes for a while.”

Speaking about her own reading as a child, she said: “I loved seeing the world through other cultures, other religions, other colours.”

Blackman’s opinion is backed by science.

A Cambridge University professor of education found that “reading fiction provides excellent training for young people in developing and practising empathy and theory of mind, understanding how other people feel and think. Empathy is increasingly being recognised as a core life skill and the bedrock for sound relationships.”

I wonder, if there had been empathy between the people of north and south Sudan would there have been a civil war?

If there was empathy between the Muslim north and the Christian south, would they have divorced so bitterly in 2011?

Growing up in the north, there was nothing in the school syllabus that taught me about the culture or people of the south.

State television did nothing to promote south Sudanese music, dance or traditions.

As an adult, I was thrilled when I read a short story by the south Sudanese writer David Lukudo, set in Khartoum in the fasting month of Ramadan.

The story follows a day in the life of a southern Sudanese young man, a Christian who is not observing the fast. For me, it was a fascinating perspective.

A completely different way of seeing my familiar city. It opened my eyes to a very different experience and another way of life, parallel to my own.

I wish I had read such stories when I was younger. And I wish that all children in the north had read literature from south Sudan.

The writer Neil Gaiman says fiction builds empathy. “When you watch TV or see a film, you are looking at things happening to other people.

“Prose fiction is something you build up from 26 letters and a handful of punctuation marks and you, and you alone, using your imagination, create a world and people it and look out through other eyes.

"You feel things, visit places and worlds you would never otherwise know. You learn that everyone else out there is a me, as well.

"You’re being someone else and when you return to your own world you’re going to be slightly changed.

“Empathy is a tool for building people into groups, for allowing us to function as more than self-obsessed individuals.”

One of the best lessons we can teach our children is that there are many different ways of looking at the world, that there are many different types of people, different lifestyles, cultures and places.

If we can expose them socially to different worlds, well and good. If not, then literature is just as good.

Chinua Achebe says: “I tell my students it’s not difficult to identify with somebody like yourself, somebody next door who looks like you.

"What’s more difficult is to identify with someone you don’t see, who’s very far away, who’s a different colour, who eats a different kind of food. When you begin to do that then literature is really performing its wonders.”

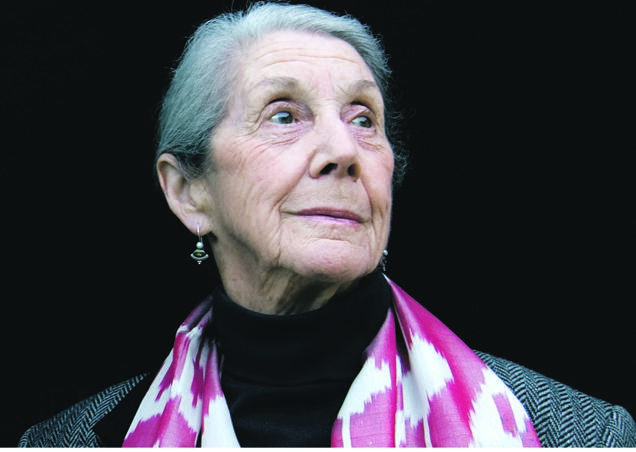

It is Nadine Gordimer who said: “My answer is: Recognise yourself in others.” In Gordimer’s writings, she enters the world of her characters with empathy and compassion.

There are tense encounters in her work, encounters between people of different races, languages and classes.

She was able to view a situation from two opposing sides, immersing herself simultaneously in different perspectives – seeing things from one side and then changing the lenses to see it more in focus or moving her position to see it from a completely different vantage.

But it was humanity she was recording all the time, humanity with its flaws and complexities.

She possessed a deep understanding of us as humans, our prejudices and our fears, the positions we take for granted, what we have and our fear of losing it.

Her consciousness was focused on a particular country and a time in history. Her characters were at perfect ease in their settings, they were one with the landscape and the circumstances of time and place.

Yet they transcended their conditions.

They are people we recognise as others and as ourselves. Despite her achievements, she did not boast. Instead this is what she said about her work: “Your whole life you are really writing one book, which is an attempt to grasp the consciousness of your time and place – a single book written from different stages of your ability.”

My brief encounter with Gordimer and the positive impression she made on me was experienced by other writers.

In an article entitled A Testimonial of Grace, published in Sahara Reporters, the Nigerian writer Ikeogu Oke, who died last month, wrote about meeting her.

His words are so eloquent and mirror exactly my own personal experience, that I will end with them.

He says: “For such a revered writer and global figure, I was surprised that she would keep me completely at ease for the nearly two hours’ meeting. Not hers the airs I had sometimes noticed from some far less accomplished writers. I could hardly believe such a great figure could embody such humility.’’

This is an edited extract from the lecture Aboulela delivered at the 4th In Memoriam Lecture for Nadine Gordimer. Aboulela is an author of five books and her work has received critical recognition for its distinctive exploration of identity, migration and Islamic spirituality

Publications

Publications

Partners

Partners