On April 12 and 13, about a dozen or so of Old Fortharians, the Class of 1968, held a reunion at the Alice Main Campus of the University of Fort Hare. These veterans of the group of 1968 had occasion to reconnect with the university that some of us were driven out of in less auspicious circumstances than can be found today. For me at least, this was a pilgrimage, a spiritual journey. It helped me to reconnect with my intellectual and spiritual roots that shaped my identity as a critical citizen and as a thought leader.

In 1968, the university had a student enrolment of less than 500 students, on one campus. Besides, the faculties of science, social sciences, arts and humanities, education, law, business, management and accounting there were no other disciplines of which the then University College of Fort Hare could boast. Only a small number of students were enrolled for postgraduate studies.

Today the university has about seven faculties. These include agriculture and health sciences, and departments of music, sport and human movement – disciplines unheard of 50years ago. There are campuses in East London and at Bhisho, and a strong postgraduate enrolment.

In August 1968, on a Friday at precisely 1pm, I was among students who sat in demonstration in front of the administration building. The sit-down strike had been in progress for five days without any sign of resolution. On the Friday the strike was broken up in military-style when a large number of armed police and military personnel charged at the peacefully gathered student body with fierce dogs. It was a frightening experience for the students, and we did not think we deserved such treatment.

Having declared the gathering illegal, the commandant barked that the students were under arrest. We were marched to our rooms to pack, and we were loaded on to the waiting trucks and buses and forcibly evicted from the campus. The buses appeared as if from nowhere, and trains that were specially procured for this operation. The students were packaged onto these vehicles unceremoniously en route to their home destinations. A few weeks later, some of the students were allowed back on the campus to resume their studies but a small number was expelled from the university altogether. For me it was the beginning of a life-long engagement in political activism as an avid opponent of apartheid and dedication to the liberation of our country.

What was memorable about that day was the fact that members of staff, mainly white academic staff, stood by watching as the students were violently removed from the campus – indeed at least one of the white academics was known to be armed! In contrast, what remains etched in my mind on that day was the courage and compassion of the church that stood in solidarity with the students. Chaplains and lecturers at the neighbouring FedSem, Desmond Tutu and TSN Gqubule braved the might of the police and military, broke the police cordon and stood with the students at their hour of need. From faraway Rhodes University, students and staff collected food to feed the starving students along the way on trains and buses home.

1968, of course, was the year of student revolts worldwide. In London, Paris, Frankfort and San Francisco students were in revolt. Students were revolting against a state of the world of conformism to the new liberal ideas of individualism and capitalism. The students sought to challenge the manner in which the contemporary society was being organised, what Herbert Marcuse, the radical philosopher of the New Left at the time called a “one-dimensional view of the world”. The students adopted the stance of becoming refuseniks, a rejection of the values of a bourgeois society.

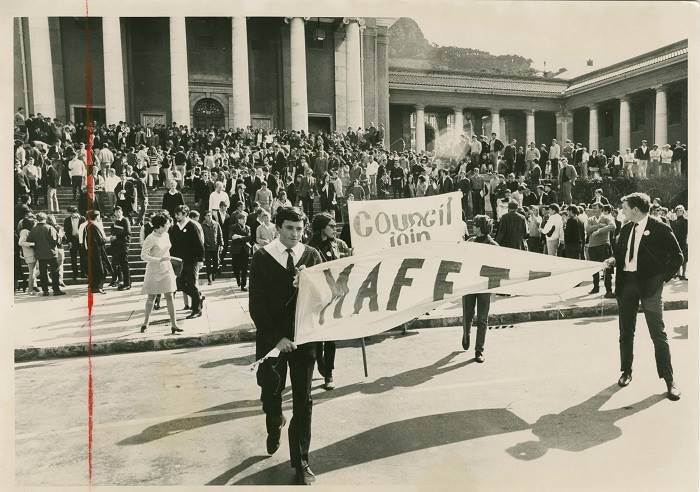

In South Africa this movement was expressed at the University of Cape Town who challenged both the university and the Vorster government about the withdrawal of the appointment of Dr Archie Mafeje as lecturer in anthropology at UCT.

UCT students staged a strike that drew the attention of the world. The Mafeje Affair has become part of the lore of UCT to this day.

At Fort Hare different social and political circumstances were at play. As in London, Paris and elsewhere Fort Hare students were objecting to the apartheid indoctrinisation of academic knowledge, to the flooding of the university with incompetent second-rate lecturers drawn from Afrikaner universities like Potchefstroom, and the pervasive presence on campus of security agents.

Fort Hare students had persisted with a tradition of non-cooperation with the university except where absolutely necessary.

For example, Fort Hare consistently rejected establishing an student representative council since the Separate Universities Act was imposed in 1960. In August 1968 the students protested at the presence of Blaar Coetzee, the then deputy minister of Bantu education at a graduation ceremony and the inauguration of Prof JM de Wet as rector. The students presented a list of demands but refused to negotiate with the authorities.

The Fort Hare 1968 Reunion then in April by this motley group of elders was significant. It was not just a nostalgic occasion, but it got down to the business of appreciating and valuing the foundations laid by this unlikely place in the professional and intellectual development of the students.

Secondly, upon being taken around the campus and remembering the university as it was in 1968, places of memory and significance, yet they could also appreciate the extent of the developments on the campus, the growth and infrastructure.

Likewise, they deplored the extent to which the small town of Alice, which was a university town of note at the time, had become dilapidated and crumbling, that key institutions like Victoria Hospital and Lovedale Institution were allowed to deteriorate to the extent that they have. Around the campus at the university it was not difficult to observe the deplorable state of the grounds and gardens compared with what they were during our time.

The highlights of the visit were two-fold: the briefing by the vice-chancellor, and the dialogue with the new generation of student leaders.

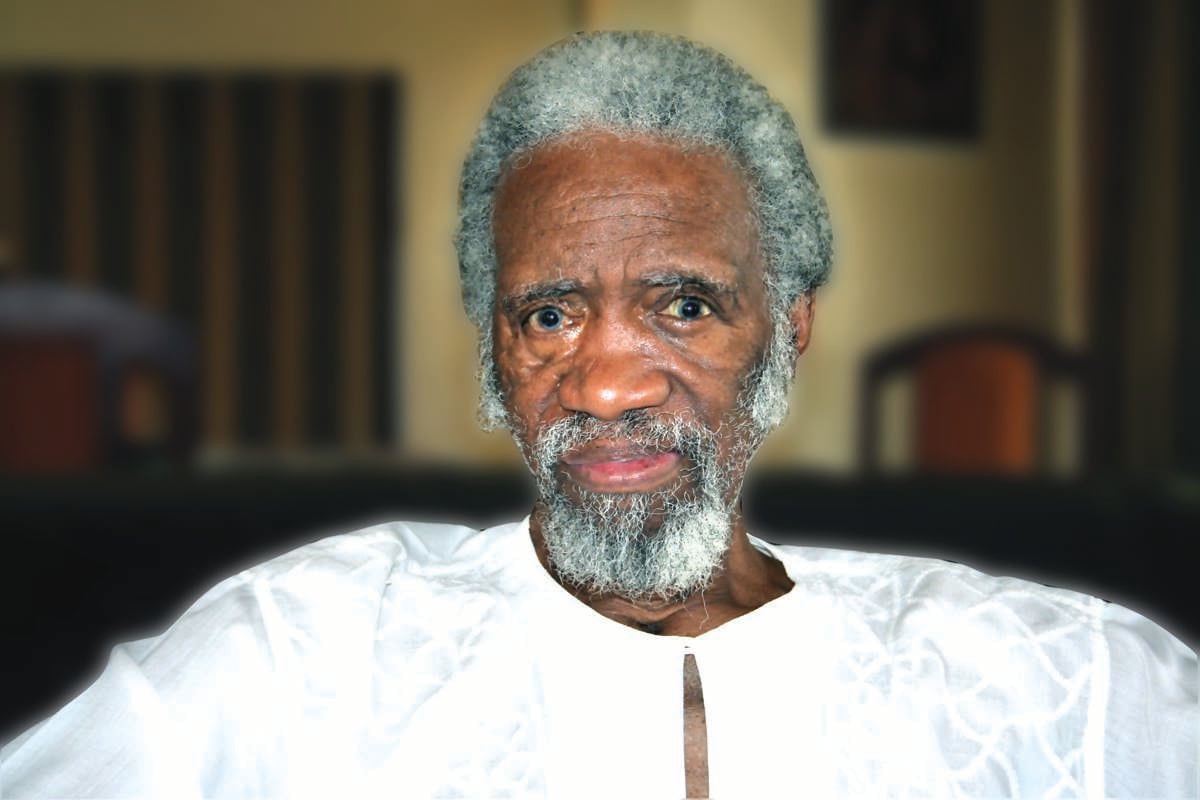

Also present among us was Advocate Dumisa Ntsebeza SC, the chancellor of the University of Fort Hare, and also a veteran of 1968.

The vice-chancellor proudly shared with us the academic and research advances that the university was making, including firsts in the success rates for chartered accountants, a health sciences faculty, and in the latest research outputs Fort Hare was among the top six universities in research output per academic nationwide.

The university proudly establishes itself as the archival centre for the records of the liberation struggle and sets itself up as a research centre on the history and politics of the liberation struggle era in South Africa.

Besides at Hunterston, Hogsback, the university has established a dedicated postgraduate research facility in order to attract research scholars and students as well as research events like seminars and colloquia.

Hunterston was the ancestral home of the late Professor Monica Wilson, herself a former student and lecturer at Fort Hare.

The negative perspectives on the university came not just from the vice-chancellor but also came from the student leadership we interacted with. It is worth noting that the 1968 Reunion had been scheduled to take place in August 2018, on the anniversary of the events of 1968. Unfortunately, the university was beset by a long-running strike by Nehawu and that meant that the university was unable to receive visitors and could not guarantee our safety.

What we received from the student leaders is the prevalence of a rape culture on campus. The students named lecturers and professors who sought sexual favours from students. There were also reports about the learning and teaching culture that was compromised by corruption and the inability of the university to treat students as mature and responsible in their academic and intellectual pursuits. The dialogue with the students showed just how similar the generations of students were but also how similar in the concerns that all students have about their university life.

We went away very positive and impressed by the caliber of student leadership that the university was producing. We were also encouraged by the cordial relationship between the vice-chancellor and senior staff in their relationship with the student leadership – something very rare these days in campus life where relations are fraught, and universities have to rely on security personnel to protect facilities from arsonists.

We decried the culture of intolerance against differing viewpoints and violence that students resort to instead of debating, arguing and convincing each other on the basis of the best ideas wins.

Finally, and on a personal note, Fort Hare can proudly boast of having produced this nation’s foremost intellectuals: academics and professionals in all walks of life. Fort Hare graduates are to be found in eminent places across the world as diplomats and politicians, scientists, researchers, educators and politicians. It strikes me as surprising that such an eminent centre of learning is so coy about its achievements and it is not trumpeting its iconic status to high heaven.

Second, it is difficult for one to understand how an institution with such a historic footprint is not even appreciated among its staff and alumni, and even by the provincial government that in part it could serve. It is about time that Fort Hare alumni exhibit pride in their university. Should any of this be possible the disruptions, theft and looting of university resources, pride in the place would mean that staff work for the betterment of the institution and not so much for what they can loot.

There should surely be more support for the vice-chancellor who seeks to bring back a disciplined life, a responsible engagement between the institution and society, a culture of academic excellence, and understanding the university to be a resource for fresh ideas and innovation. None of that seems to be motivation enough for the character of Fort Hare to be improved from within.

Lastly, I take the view that places like Fort Hare, for example just like UWC did under Jakes Gerwel and Brian O’Connell who profiled the University of the Western Cape as the “intellectual home of the Left”, need to break away from the mentality of a subservient Cinderella among universities in the country, and seemingly to accept its second-rate status.

Perhaps Fort Hare could put its best foot forward and claim its heritage, especially in the quality of black leaders it could produce for South Africa and Africa as a whole.

In other words, Fort Hare could draw from its activism roots and present itself as an institution where a new generation of moral and critical thinking leaders of society in politics, business, diplomats, the professions, science, and law are produced. For that Fort Hare could embrace a Black Consciousness philosophy that claims to train a new generation of proud, black and intelligent, sophisticated men and women who could stand their own in a competitive world out there. I bet that such a university would be an attractive brand to students, parents and employers alike.

For that to happen much needs to change within the institution today.

Publications

Publications

Partners

Partners